On a warm afternoon in early fall, red-tailed hawks swooped low over fields of soybean on Firetown Road in Simsbury, Connecticut. Four abandoned barns, their weathered facades gleaming silver in the sun, stood by the roadside, vestiges of the Connecticut River Valley’s once-thriving tobacco farms.

You wouldn’t know by looking at it, but this peaceful, unassuming place—a mix of meadows and woodlands on the outskirts of Hartford—has a fascinating story to tell. It was on this property that a young Martin Luther King Jr. spent summers as a field hand alongside migrant workers from around the country. Historians say the experience shaped King’s worldview in important ways.

Photo: Kesha Lambert

In September 2021, we joined the Town of Simsbury in permanently protecting the historic and culturally significant property, known locally as Meadowood. The 288-acre parcel, once a thriving tobacco farm, looks about the same as it did more than 75 years ago. The landscape—and the experiences that unfolded here—offers important connections to Civil Rights history in Connecticut.

“We are pleased to have worked with the Town of Simsbury and many partners to preserve the Meadowood property for generations to enjoy the beauty of this place and learn from the special and often overlooked history of this land,” said Walker Holmes, Trust for Public Land’s Connecticut state director.

Until recently, that history was at risk of being lost altogether. The property had been owned by a developer, and any plans to build on the land would have meant knocking down the historic barns and paving over farmland. In 1944, while much of their regular workforce was away at war, tobacco growers in Connecticut recruited seasonal laborers from around the country to keep their farms running. The summer before his freshman year at Atlanta’s Morehouse College, King joined a group of his fellow students who ventured north to work in these fields. He returned three years later for another stint as a farmhand, living in a dormitory on the farm and venturing into downtown Simsbury and the city of Hartford to go to church, dine in restaurants, and watch movies at the local theater.

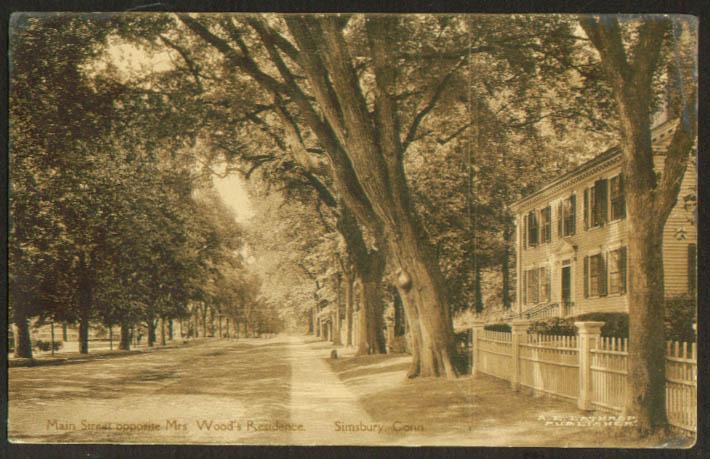

Main Street, Simsbury, Connecticut Photo: Wikipedia

It might sound like an ordinary way for an American teenager to spend his summers, but for King and his classmates at the historically Black Morehouse College, it was transformative. In letters home during those summers, King described the liberating experience of getting out from under the Jim Crow laws of the segregated South. “I had never thought that any person of my race could eat anywhere, but we ate at one of the finest restaurants in Hartford,” he wrote to his mother.

“It was a crucial time of his life,” said Dr. Clayborne Carson, the Martin Luther King Centennial Professor of History at Stanford University and founding director of the university’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. “It was the first time he was out of the South for an extended time. So he really experienc[ed] places where southern-style segregation didn’t exist. And that was impressive for him.”

In The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., edited by Carson and published in 1998, King marveled at the freedoms he experienced during his trips to the North. “After that summer in Connecticut,” he wrote, “it was a bitter feeling going back to segregation.”

Despite the property’s captivating history, there has never been anything at the site to mark its importance. “Not many people realize that Martin Luther King Jr. spent time in Connecticut,” says Honor Lawler with Trust for Public Land. “In part I think that’s because until now, there has been no formal place that celebrates that.” In the 1980s, the dormitory King stayed in burned to the ground during a training exercise for volunteer firefighters; that was before his time in Simsbury became widely known after his letters were made public in the 1990s.

Historic barns at Meadowood, in Simsbury, Connecticut Photo: Kesha Lambert

Following a grassroots citizen petition process and special town meeting that put the question of the Meadowood purchase on a referendum ballot in May, Simsbury residents authorized $2.5 million for the purchase of Meadowood. The vote passed by a resounding 87 percent. Additional funding for protecting the land comes from the State of Connecticut through the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, Department of Agriculture, and State Historic Preservation Office, as well as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the Highlands Conservation Act, the George Dudley Seymour Trust, and many generous individuals, foundations, and funders.

As part of the purchase, the state of Connecticut will hold an easement for recreational access on nearly 130 acres, while about 120 acres is to be preserved as working farmland. The Town of Simsbury has 24 acres set aside for future municipal needs, and 2 acres are designated for historic preservation, including interpretive elements that will share the special history of the land. Eventually, supporters hope to restore the remaining barns and install signage about the site’s history.

Meadowood’s protection is part of a broader movement throughout the state to recognize and remember this little-known chapter in civil rights history. Across the country, just 2 percent of sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places focus on the experiences of Black Americans. This collective oversight deprives all Americans of a full understanding of the history of our nation. There is real and urgent risk that many important places will be lost to development or neglect and that the stories and experiences of the people connected to these places will be forgotten.

Now that it is protected, the Meadowood land will likely be included on the Connecticut Freedom Trail, a network of sites associated with Black history across the state. Launched in 1996, the trail includes more than 145 places, including burial sites, houses, churches, schools—even a battlefield and whaling ship. On Dr. King’s birthday earlier this year, the Simsbury Free Library unveiled a memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. in honor of his summers in the town. And about a decade ago, a group of Simsbury High School history students researched and produced a 14-minute documentary called “Summers of Freedom: The Story of Martin Luther King Jr. in Connecticut.”

Conservation of the Meadowood property is the latest chapter in our ongoing efforts to preserve places that help tell the story of Black life in America—reminders of the lessons our history has to offer, and a connection to our nation’s shared heritage.

Since 1980, we’ve helped the National Park Service save and restore many of the buildings in around King’s childhood home in Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park is now one of Atlanta’s most popular destinations, welcoming roughly a million visitors a year to visit the home where Dr. King was born in 1929, the tomb where he’s buried, and the church where he preached his first sermon and was ordained as a minister at just 19 years old.

Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park in Atlanta, GA. Photo: Christopher T. Martin

According to Catherine Labadia, a staff archaeologist with the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office, the farm fields in Simsbury may have been where King “found his future calling as a minister.” In Connecticut Preservation News, Labadia described how King honed his skills as a preacher, leading prayers and giving sermons to the other students on the farm. Labadia’s office has received a grant from the National Park Service to research and highlight King’s connection to the state.

“Although Connecticut also was characterized by racial and social inequalities,” Labadia writes. “King saw a situation that was better than where he came from and, with his youthful passion, a vision for a better future.”

This article was originally published in January 2021. It was updated in October 2021 to reflect the permanent protection of Meadowood.

Lisa W. Foderaro is a senior writer and researcher for Trust for Public Land. Previously, she was a reporter for The New York Times, where she covered parks and the environment.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.