Remembering a true trailblazer

King’s Canyon, Sequoia, Yosemite—today, they’re among the most widely recognized parks in the world. But in the early 1900s, the first national parks were unfinished, untested, and protected only on paper. They faced threats from poachers who picked off wildlife and illegal grazing that flattened high-mountain meadows. Infrastructure was minimal, communication challenging, and living conditions tough.

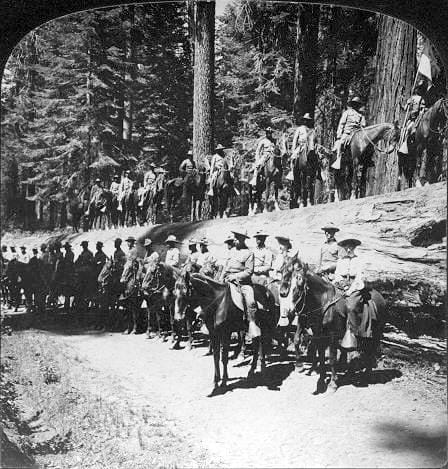

Into this Wild West of park stewardship arrived Charles Young, commander of the all-black 10th Cavalry unit—better known as Buffalo Soldiers. The men arrived in the Sierra from the military base at San Francisco’s Presidio after 16 days on horseback—and immediately got to work.

In one summer, Young and his men made more progress in Sequoia National Park than previous units had in the three years prior, building miles of access roads that still serve visitors today. Their efforts quite literally laid the groundwork for everyday Americans to experience the Sierra—and learn firsthand why the parks were worth protecting.

Young tackled this formidable task with a conservationists' eye to safeguarding Sequoia's natural resources. In his final report from the park, Young wrote:

There are enough beautiful mountain views, delightful camping sites, and water courses stocked with fish to constitute a national park where the overworked and weary citizens of the country can find rest, coolness, and quiet … . Indeed, a journey through this park … will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are, with their clothing of trees, shrubs, rocks, and vines … .

In this, then, lies the necessity of forest preservation. The United States should learn its lesson in time.

From the first black superintendent of a national park, Young would go on to become the first black colonel in the United States Army. Confronted at every step along the way with the overwhelming bigotry of his time, Young nonetheless served a distinguished military career that spanned four continents.

In 2013, The Trust for Public Land helped protect Young's family home in Wilberforce, Ohio, for a new national monument. When complete, the Charles Young House will tell the too-often forgotten story of a trailblazer whose service made some of our most treasured parks what they are today.