The Trust for Public Land has transformed hundreds of schoolyards across the country into green, welcoming public parks.

The Trust for Public Land has transformed hundreds of schoolyards across the country into green, welcoming public parks.

Escobar is one of the many parents who’ve helped plan improvements to the schoolyard, which will likely go to construction this summer. “We’re going to get more trees, more shade, take away some of the concrete, I think, and make a soccer field,” she says. “We’re happy to have been a part of it, because we have to do something to help our kids.”

Burns from hot surfaces are just one unintended health hazard of the standard asphalt schoolyard design. “Our kids were coming home sunburned and dehydrated, even from just being out there for a short time at recess. They had headaches. We worried about heat stroke,” says Ricardo Cortes. He’s the parent of a kindergartener and a third grader at Melrose Leadership Academy in East Oakland. Cortes loves his kids’ school and says they’re getting a great education. But just like at International Community School, the yard at Melrose is mostly concrete, surrounded by a tall chain-link fence.

Cortes works as a policeman. “I’ve spent some time in prisons. When we first started at this school, I thought, ‘Oh my god, it looks like a prison,” he says. “We say we care for our kids? Why are we putting them on slabs of asphalt that get horribly hot, with nothing for them to do?”

Researchers are learning more about how rising temperatures will affect all aspects of our lives—including kids’ ability to succeed in school. A recent study from UCLA’s Department of Public Policy and the Luskin Center for Innovation found that every one-degree increase in average outdoor temperature over a school year reduces student performance on standardized tests by one percent.

So Cortes joined a group of Melrose parents who’d long been fighting for a safer, more engaging schoolyard. “The administration was very supportive of us getting involved, but they made it very clear they didn’t have the bandwidth to do anything—we were on our own,” says Kim Walker, who helped organize Melrose parents around this issue when her daughter started kindergarten nine years ago. “I understand! We’re pushing for significant changes, and the district is strapped. They can’t take it on alone either. This should be a concern for the whole community, and not just up to the school district, when public education is already struggling so much.”

Walker has had to dissuade parents who, at wits’ end, imagined scaling the fence under the cover of darkness and taking a jackhammer to the concrete.

“I understand their desperation, but we were able to work a little more systemically instead,” she says. Parents applied for grants and lobbied at the district and state levels. They gathered input from teachers, neighbors, and the community to create a playground master plan. And they devoted hours of their weekends to making what changes they could: building garden boxes, planting, watering, and weeding.

“I understand their desperation, but we were able to work a little more systemically instead,” she says. Parents applied for grants and lobbied at the district and state levels. They gathered input from teachers, neighbors, and the community to create a playground master plan. And they devoted hours of their weekends to making what changes they could: building garden boxes, planting, watering, and weeding.

“We were like the sea hitting against the seawall trying to find a crack. We went years without much progress,” says Walker. “Until we got connected to The Trust for Public Land.”

Since 2017 The Trust for Public Land has been working alongside the Melrose school community to plan, fund, and build a greener schoolyard. “They gave us a big boost in terms of funding, technical expertise, and community organizing capacity,” Walker says. “They helped us take many more voices and perspectives into account.”

In late 2018, The Trust for Public Land completed the first phase of green upgrades at Melrose, replacing pavement with gardens full of native plants and planting 16 new trees that will grow to cover much of the yard in shade.

“The Trust for Public Land’s effort is a step in the right direction,” says Cortes. “But we still have a lot of work to do.” He means in terms of upgrades to his kid’s school but also a broader rethinking of schoolyard design, funding, and accountability. So much of the impetus for transforming the schoolyard came from parents like him—with the time and resources to get deeply involved for years at a time. “The way it is now, change only happens at the schools where parents can afford that level of commitment,” he laments. “That’s not right.”

Void of trees, grass, and shade, badly designed schoolyards—along with blacktop highways, dark rooftops, and other city infrastructure—trap heat from the sun, increasing temperatures throughout the entire neighborhood. This is known as the “heat island effect,” and it’s part of why cities are often much hotter than surrounding rural areas.

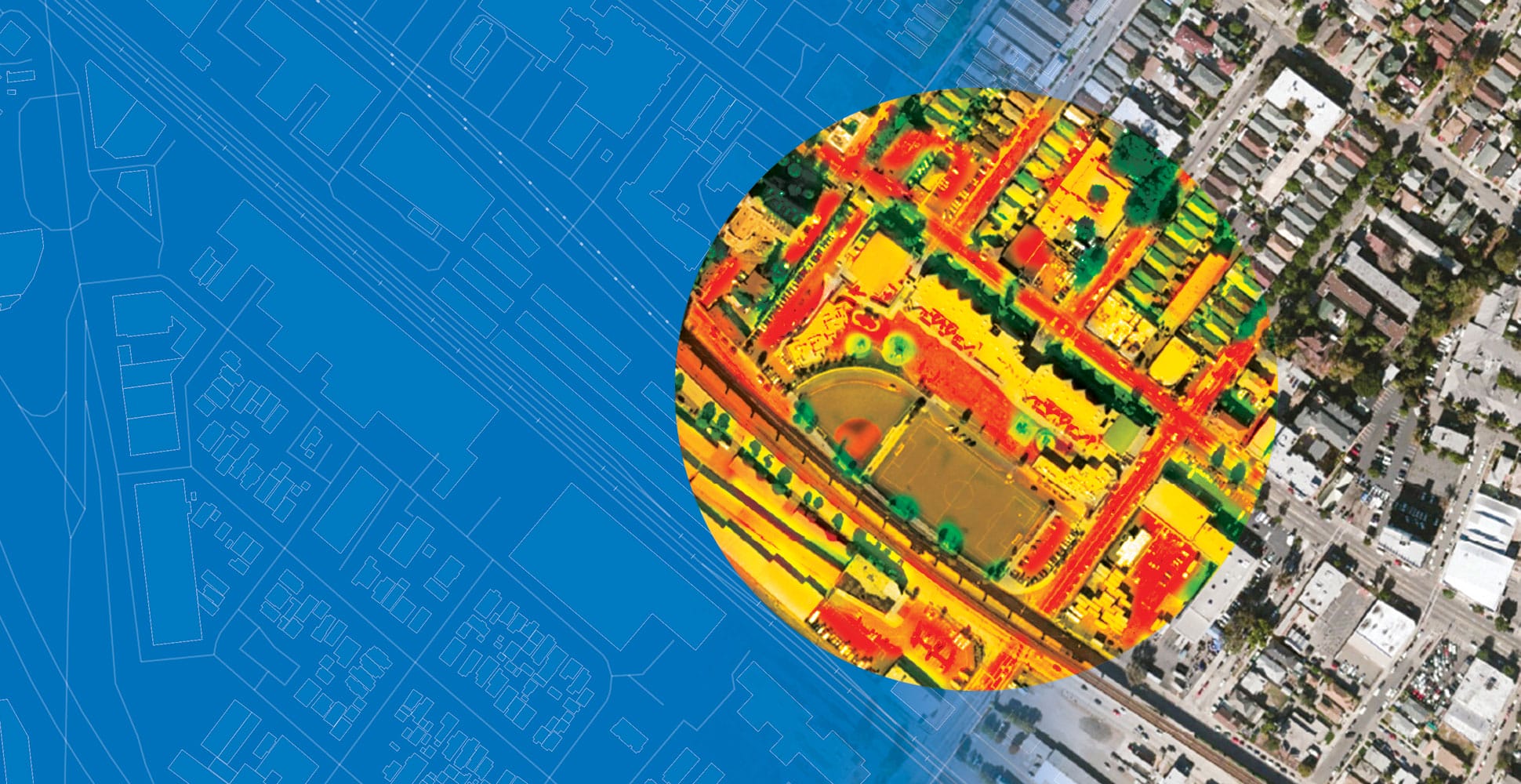

Even within a city, heat risk varies widely. Neighborhoods with more mature trees, bigger lawns, and green parks stay noticeably cooler than neighborhoods with more pavement, denser buildings, and less shade. The Trust for Public Land has mapped the heat island effect at a neighborhood scale for over 14,000 municipalities in the United States. On the map of Oakland, the neighborhoods around International Community School and Melrose Leadership Academy are dark red, indicating they’re among the hottest spots in the city.

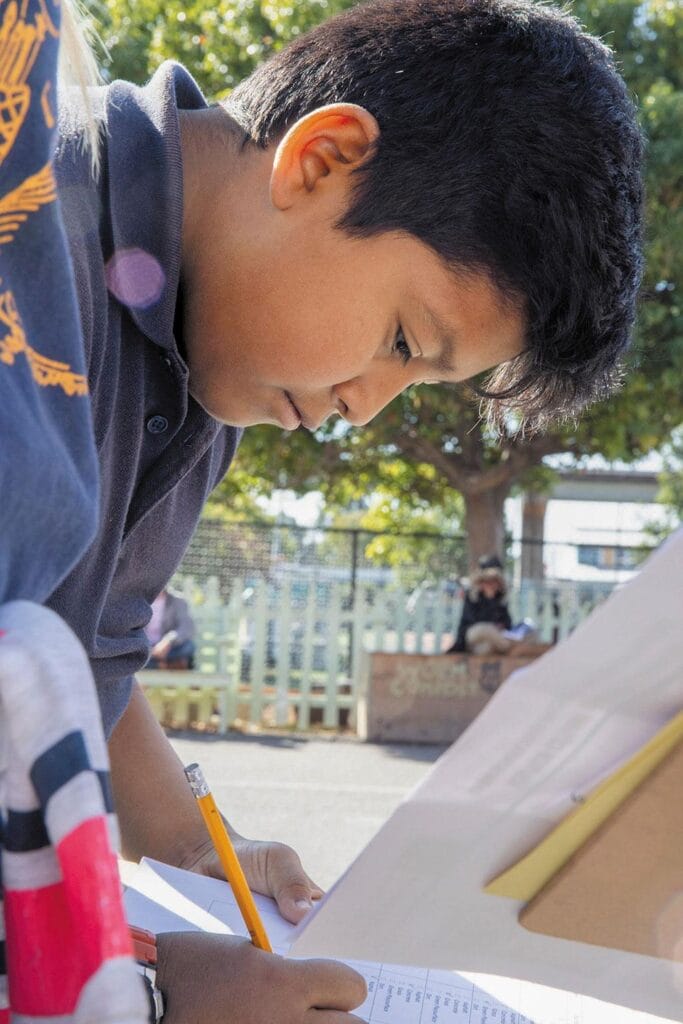

Students at Oakland’s International Community School gather data about heat risk on their playground.

Students at Oakland’s International Community School gather data about heat risk on their playground.

The Trust for Public Land has transformed hundreds of schoolyards across the country into green, welcoming public parks.

The Trust for Public Land has transformed hundreds of schoolyards across the country into green, welcoming public parks.

In the next five years, The Trust for Public Land aims to build green schoolyards in 20 more school districts, using cutting-edge data and mapping to pinpoint the neighborhoods at greatest need for cooling infrastructure.

In the next five years, The Trust for Public Land aims to build green schoolyards in 20 more school districts, using cutting-edge data and mapping to pinpoint the neighborhoods at greatest need for cooling infrastructure.