Executive Summary

Americans’ sense of community is being sorely tested. Studies show that people are experiencing extreme levels of loneliness, polarization, and division. Places that historically brought people of different backgrounds together have faded in importance or have themselves become battlegrounds, from houses of worship to social clubs to school boards of education. Parks remain a neutral public gathering place where community members can meet, collaborate, and become empowered. Park leaders can foster those connections through a variety of approaches, programs, and partnerships.

Across the United States, people are divided by politics, economics, race, ethnicity, and ideology. A looming presidential election and contentious wars abroad have raised those tensions further.

Across the United States, people are divided by politics, economics, race, ethnicity, and ideology. A looming presidential election and contentious wars abroad have raised those tensions further. More than three-quarters of major cities were more racially segregated in 2019 than in 1990.

More than three-quarters of major cities were more racially segregated in 2019 than in 1990. Half of American adults report feeling lonely, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the isolation that many experience.

Half of American adults report feeling lonely, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the isolation that many experience. Two-thirds of adults say they feel little to no confidence in the future of our political system.

Two-thirds of adults say they feel little to no confidence in the future of our political system.

Dakai Brown of Bridgeport, Connecticut, like children around the country, benefits tremendously from communities where social connections are strong. High-quality parks are a contributing factor to social capital, which can deliver lower mortality, reduced depression, and increased economic mobility.

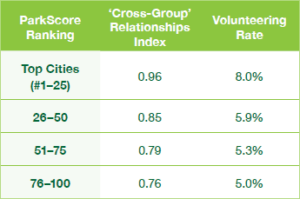

According to our analysis of park systems across the 100 most populous U.S. cities, residents of cities with the highest ParkScore® rankings are more socially connected and engaged with their neighbors than residents who live in cities with lower-ranking park systems.

According to our analysis of park systems across the 100 most populous U.S. cities, residents of cities with the highest ParkScore® rankings are more socially connected and engaged with their neighbors than residents who live in cities with lower-ranking park systems. In the top 25 ParkScore cities, there were on average 26 percent more social connections between low- and high-income individuals (“cross-group” relationships) than in lower-ranked cities. Also in those cities, people were 60 percent more likely to volunteer than those living in lower-ranked cities.

In the top 25 ParkScore cities, there were on average 26 percent more social connections between low- and high-income individuals (“cross-group” relationships) than in lower-ranked cities. Also in those cities, people were 60 percent more likely to volunteer than those living in lower-ranked cities. About two-thirds of ParkScore cities are investing in community engagement by compensating residents for their input or hiring full-time community engagement staff. Park leaders are also hiring and training community organizers to create programs for green spaces to encourage social connection.

About two-thirds of ParkScore cities are investing in community engagement by compensating residents for their input or hiring full-time community engagement staff. Park leaders are also hiring and training community organizers to create programs for green spaces to encourage social connection. According to the Center for Active Design, people who live near parks are more likely to be satisfied with their local government. In two dozen U.S. communities, those living near popular public parks reported 29 percent greater satisfaction with their parks and recreation departments, 14 percent greater satisfaction with their police, and 13 percent greater satisfaction with their mayor, compared with people not living near parks.

According to the Center for Active Design, people who live near parks are more likely to be satisfied with their local government. In two dozen U.S. communities, those living near popular public parks reported 29 percent greater satisfaction with their parks and recreation departments, 14 percent greater satisfaction with their police, and 13 percent greater satisfaction with their mayor, compared with people not living near parks.

Develop civic infrastructure. That includes hosting voter registration and polling sites in parks; training residents in community engagement; permitting public protests; and welcoming community organizers. These activities elevate the democratic ideal of the public square.

Develop civic infrastructure. That includes hosting voter registration and polling sites in parks; training residents in community engagement; permitting public protests; and welcoming community organizers. These activities elevate the democratic ideal of the public square. Invest in community engagement and organizing. When planning an individual park or an entire master plan, park agencies should avoid a top-down approach and instead seek to consult, involve, and empower the community.

Invest in community engagement and organizing. When planning an individual park or an entire master plan, park agencies should avoid a top-down approach and instead seek to consult, involve, and empower the community. Activate park programs inspired by residents. Park leaders can bring diverse groups together through creative and culturally specific programs that engage new audiences and park user groups. These programs should reflect the cultures, interests, and priorities specific to that community.

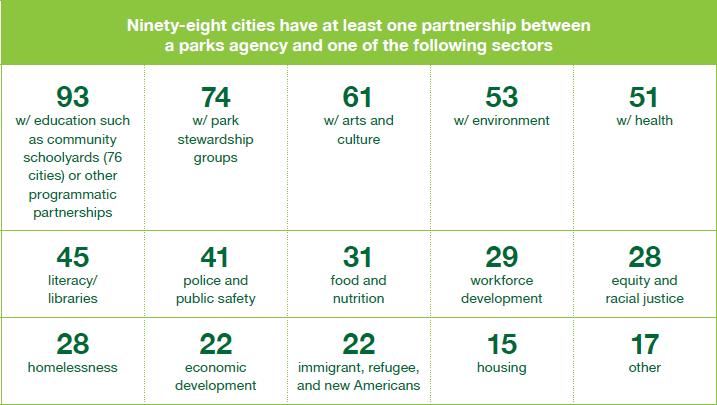

Activate park programs inspired by residents. Park leaders can bring diverse groups together through creative and culturally specific programs that engage new audiences and park user groups. These programs should reflect the cultures, interests, and priorities specific to that community. Build strategic partnerships. Parks departments should develop partnerships with organizations that bolster park stewardship, the arts, public health, and literacy. Less typical though equally important goals include job training, housing stability, and immigrant inclusion.

Build strategic partnerships. Parks departments should develop partnerships with organizations that bolster park stewardship, the arts, public health, and literacy. Less typical though equally important goals include job training, housing stability, and immigrant inclusion.

It is no longer enough for cities to create high-quality green spaces. To create strong connections with the community and between residents, parks

departments must activate those spaces with culturally representative programs. Photo: Andy Richter

Sherry Taylor, a participant in Raleigh’s On Common Ground program, attended an outdoor viewing party for the Women’s Soccer World Cup at the city’s Moore Square and met several neighbors, including one who has since become a good friend. Photo: Paul Atkinson

THE PROBLEM: America’s Declining Social Capital

“My daughter fell in love with women’s soccer that night,” Taylor recalls. And Taylor, herself, forged a new and critical friendship with a woman she might never have met otherwise. Also a single mother, the other woman and Sherry have grown close and now regularly carpool and help each other with childcare.

“I’m able to pick her daughter up if she can’t, whether because of work or a medical appointment, and vice versa,” Taylor explained. “It’s hard being a single parent, and it’s just good to have someone else to lean on and bond with.”

This kind of neighborly camaraderie is known as social capital, “the ways in which our lives are made more productive by social ties.”

But studies also show that social capital has declined in recent decades and that Americans confront polarization along political, economic, ideological, racial and ethnic lines.

One study found that 81 percent of major metropolitan areas were more racially segregated in 2019 than they were in 1990. Another sign that our shared sense of community has eroded is the nationwide epidemic of loneliness. A recent study revealed that about one in two adults in America experiences loneliness—with even higher levels among young adults, people with lower incomes, and people of racial and ethnic minority backgrounds.

THE HYPOTHESIS: Parks Can Help Community Cohesion

At a time when Americans’ trust in many public institutions has sunk to disturbing levels, parkgoers report more positive attitudes.

For example, almost two-thirds of American adults express little to no confidence in the future of our political system. By contrast, people who live near parks are more likely to be satisfied with their local government.

In the Assembly Civic Engagement Survey of over 5,000 people in 26 U.S. communities, those living near popular public parks reported 29 percent greater satisfaction with their parks and recreation departments, 14 percent greater satisfaction with their police, and 13 percent greater satisfaction with their mayor, compared with to people not living near parks—an effect that was even stronger when parks were well-maintained and easily accessible. The findings were controlled for age, Hispanic origin, number of children, political party affiliation, health status, and other factors.

So in 2024 TPL endeavored to explore and expand the existing body of evidence that suggests a link between high-quality park systems and measures of social connectivity.

Parks departments are increasingly creating programming within their green spaces to attract community participation. Free or low-cost exercise

programs, like the one at Denver’s Mestizo-Curtis Park, are a great way to get community members moving while fostering social connection.

Students at The Pacific School in Brooklyn, New York, explore the new plants in the renovated Community Schoolyard® garden during the ribbon cutting ceremony in June 2023. These spaces are not just for students. The schoolyards are open to the public after school hours and on weekends to ensure that neighbors have close-to-home access to high-quality park space. Photo: Alexa Hoyer

AN EXPLORATION: Methodology

First, TPL’s annual ParkScore® index ranks parks systems in the 100 most populous U.S. cities based on five factors: access, equity, acreage, investment, and amenities. Additional information on the methodology can be found at tpl.org/parkscore/about.

Second, this year TPL surveyed all public and private organizations managing publicly accessible parks across the 100 most populous U.S. cities to learn how they’re activating their systems to bridge divides between groups that, at best, have little contact with each other and, at worst, experience tension or hostility. A total of 868 examples were submitted from 208 different organizations. Additional details on this survey of park agencies, including methodology and additional findings, can be found here.

Third, data scientists at TPL’s Land and People Lab investigated the association between cities’ ParkScore index rankings and their social capital, as measured by two indicators from the Social Capital Atlas: economic connectedness and rates of volunteering. The researchers behind the Social Capital Atlas developed these indicators by analyzing billions of Facebook relationships for the 72 million U.S. adults aged 25–44 who use Facebook (84% of all U.S. adults aged 25–44). Economic connectedness, or “cross-group” relationships, measures the percentage of friendships between low- and high-income individuals in a given geography, while the volunteering rate measures the percentage of people who are affiliated with a volunteering group. The statistical analysis evaluated the association between a city’s park system quality and social capital while controlling for other factors such as race/ethnicity, urbanicity, transiency, poverty, education, and family structure.

Fourth, with support from the Walmart Foundation, TPL collaborated with nine smaller cities to field-test several tactics for activating park systems and programs in order to strengthen social capital.

“Parks and public spaces are part of that focus,” said Melissa Rhodes Carter, the Walmart Foundation’s senior manager for Community Resilience. “They can play an important role in providing opportunities for people to form relationships that have the potential to help us all live better.”

A Caring and Connected Communities grant helped TPL launch its On Common Ground program in 2023. That program began with the release of “The Common Ground Framework: Building Community Power Through Park and Green Space Engagement,” a paper that presented a theoretical three-part model for building community relationships, community identity, and community power.

Following the paper, TPL launched an intensive effort to engage park agencies in nine communities across the United States to test methods of uniting residents of different socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, and generational backgrounds.

“We want to learn from the projects and then share data, tools, and best practices with a wide swath of practitioners,” said Cary Simmons, director of Community Strategies at TPL, who is leading the On Common Ground program. “Essentially, we’re field-testing activities that we hypothesize will have broad applications.” Trust for Public Land is currently evaluating and plans to publish the results of each city’s efforts, but early case studies from several communities are included in the next section.

In the pages that follow, we present the results of these four research efforts—beginning with some overall findings on social connectedness and continuing with findings that support four key strategies for building social connections.

Mariano Rodriguez (left) and Collin McSpirit stroll on the boardwalk in Bridgeport, Connecticut’s Seaside Park. At a time when Americans express

feelings of loneliness, isolation, and disconnection from neighbors, shared public spaces are important in helping people form and maintain

relationships. Photo: Kristyn Miller

THE RESULTS: Key Strategies & Case Studies

Table 1

Data source: TPL analysis comparing two measures of social capital from the Social Capital Atlas (https://socialcapital.org/), economic connectedness (‘cross-group’ relationships) and volunteering rate, with TPL’s measure of park system quality—the ParkScore Index.

Trust for Public Land’s research reveals that residents of cities with the highest ParkScore® rankings are more socially connected and engaged with their neighbors than residents who live in cities with lower-ranking park systems (Table 1).

In the top 25 ParkScore cities, for example, there were, on average, 26 percent more social connections between low- and high-income individuals (“cross-group” relationships) than in lower-ranked cities.

Also in the top 25 ParkScore cities, people were 60 percent more likely to volunteer than those living in lower-ranked cities.

These patterns held after controlling for race/ethnicity, education, poverty, urbanicity, family structure, and transiency.

In layering those findings with TPL’s 2024 survey responses and with reports from the nine On Common Ground communities, four key strategies for building social connections emerged. They are:

Developing civic infrastructure

Developing civic infrastructure Investing in community engagement and organizing

Investing in community engagement and organizing Activating and creating bespoke park programs that reflect the community’s needs and preferences

Activating and creating bespoke park programs that reflect the community’s needs and preferences Building strategic partnerships

Building strategic partnerships

Dr. Hahrie Han, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University who studies democracy and civic engagement, said that over the past half-century, American society has seen a withering of the sorts of common spaces that allow people to engage with one another.

“The audacious, beautiful, and exciting promise at the heart of democracy is the idea that putting people into community with each other creates opportunities to learn the capacities, skills, and motivations needed to forge a common life together,” she said. “So it’s ever more important that we have places like parks where people naturally encounter other people. It’s through those encounters that common interests can emerge that are grounded in, but also transcend, self-interest. I see things like parks as an integral part of our civic infrastructure. When we don’t have a multiplicity of those spaces, we know that people can revert back to more parochial tendencies that can create the kind of divisiveness we see in some parts of our society.”

This idea—that parks are an integral part of our civic infrastructure—is more than an accidental by-product. In the ParkScore survey, nearly all cities (91 of 100) reported they’re actively developing civic infrastructure, such as hosting voter registration drives and polling sites in their park systems (Table 2). Other examples include training community members in civic engagement, allowing public protests at park facilities, and welcoming community organizers. These efforts engage people as citizens and thereby revive the democratic ideal of the public square.

Table 2

Data source: 2024 TPL City Park Facts Survey of all public and private park organizations across the 100 most populous cities. The counts reflect the number of cities with at least one organization reporting the given activity.

The 15 advisory council members reflect the city’s rich racial and ethnic diversity. Using some of their On Common Ground funds, BREC compensated committee members with $1,000 stipends, hired a consultant to lead conversations, and paired up the council members to plan community engagement events.

“It was really important for us to introduce the council to [the issue of racism] as soon as possible,” said Andrea Roberts, BREC’s chief operating officer. “We have an unfortunate history here in Baton Rouge, where segregation was a thing even after the federal government said it was illegal. This continued in our community for years. So people are hurting from that and there’s resentment. Those things need to be talked about.”

The work of the community advisory council, which met every month for a year, included a series of community events, each hosted by two council members from different geographic areas and different racial or ethnic backgrounds. BREC provided a budget and guidance, but the teams were given creative freedom. Events ranged from a party for children to make mini-Mardi Gras floats to a Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration in a local park.

“We all think differently, right?” said Levar Robinson, a member of BREC’s Community Advisory Council. “But when you sit down and have a conversation, [you’d be surprised by] the similarities you may have. I think when you go with an open mind, you’re thinking positive, you’re respecting the person. You’re not attacking the person, [you are attacking] the problem.”

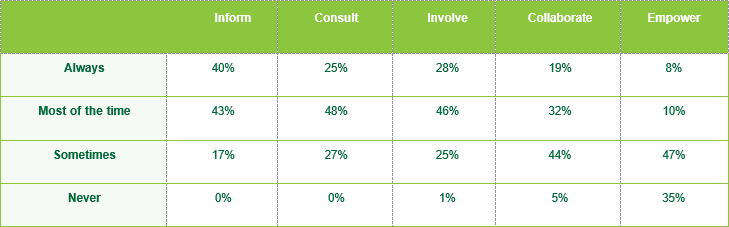

In most ParkScore cities, park agencies’ primary community engagement tools are public meetings. This can result in a top-down approach in which the community is only superficially engaged.

Some parks departments employ the International Association for Public Participation’s (IAP2) “Spectrum of Public Participation” model, which features a continuum of citizen engagement: inform, consult, involve, collaborate, empower. In the 2024 TPL survey of the nation’s 100 largest cities, public park agencies were nearly five times more likely to inform the public (“always” or “most of the time”) than to empower the public (Table 3). Only 18 percent of responding cities said they empower the local residents by placing final decision-making in the hands of the public.

Table 3: When planning park projects, systems, and recreation programs, how often does your agency inform, consult, involve, collaborate, and/or empower local residents?

Data source: 2024 TPL City Park Facts Survey of all public and private park organizations in the 100 most populous cities. The percentages in this table reflect only each city’s primary park and recreation agency. Sample size = 81 unique cities.

According to TPL data, these trends are on the upswing as park officials actively engage resident collaborators. TPL’s research suggests that cities that shift their efforts toward the right end of the spectrum are more likely to move the needle on measures of social capital.

Across the country, about two-thirds of ParkScore cities are investing in community engagement, either paying community members for their input or hiring full-time community engagement staff (55). Park leaders are hiring and training community organizers and activators to pro- gram their green spaces as hubs for community connection.

“If you show up and say, ‘Here is your brick box of a rec center,’ for example, and the community says they hate it, you won’t get any buy-in to whatever it is you’re building,” he explains. “If you include the community from the outset, you build in participation, volunteerism, advocacy, and stewardship.”

Baltimore City Recreation and Parks now includes the community at every stage. It holds periodic “participatory urbanism” forums, giving residents an opportunity to weigh in on big-picture issues like policy and capital programs. It also invites community members to charrettes—design workshops with park professionals and landscape architects to brainstorm ideas for new green spaces or park renovations. Increasingly, Baltimore is asking children what they think, too.

“When we did playground designs, there was a roomful of adults,” Almaguer says of past projects. “But what do the kids want?” For two new playgrounds at Leon Day Park and Alhambra Park, the department held charrettes at a local rec center for 5- to 12-year-olds. The children designed and built their own playgrounds using popsicle sticks, pipe cleaners, marshmallows, and gumdrops. “We gave them dot stickers to place on things they wanted, like swings and tall towers for climbing,” he added, “and they also voted.”

Baltimore is also taking steps to strengthen its network of park friends groups—and to nurture new ones. The parks department invites 30 such groups to quarterly “Grow” workshops. Each meeting has a different theme—permits, say, or maintenance. “Even though we have a topic, we leave it open for cross-pollination between the groups,” Almaguer added. “So they might say, ‘Hey, what do you do about insurance?’ or ‘How do you write a grant or run an event?’ It’s an opportunity for peer-to-peer conversations.”

Since 2019, the department has also helped three under-resourced neighborhoods start new friends groups. “We all cherish and love parks,” he said. “It is your place of social capital; it’s your respite; it’s your oasis.

Whether you come from an affluent community or a low-income community, there are the same needs.”

TPL has sought to elevate community in all its projects, whether large-scale land protections or small city parks. Community engagement—in public meetings, at farmers markets, in classrooms, and elsewhere—begins long before a formal park design is created or a shovel goes in the ground. It often endures—to propel programming and stewardship—after officials snip the ribbon on opening day. Increasingly, TPL is identifying resident experts in the communities where it works, compensating them for conducting surveys, assisting in workshops, or serving as a liaison with fellow residents.

A little more than half of ParkScore cities (51) are responding to division and polarization by activating their parks—creating programs or facilitating events—with a heavy focus on bringing unlikely groups together, through a series of creative and culturally specific programs that engage new audiences and park user groups. The data suggest that creating high-quality, accessible parks isn’t enough. If cities want to improve and grow social cohesion, they need to create opportunities for residents to come together, and those opportunities should reflect the cultures, interests, and priorities unique to that community.

Tulsa’s weekly Global Gatherings, which drew nearly 4,500 people, highlighted traditions from around the country and the world, including Native American dress and dancing in order to immerse community members in the many rich cultures present throughout the city. Photo: Courtesy of Gathering Place

One of the 100 cities evaluated by TPL’s ParkScore® index, Tulsa developed its five-year-old Gathering Place park with the goal of uniting Tulsans of all backgrounds. The 66-acre park, which had a $465 million price tag, may well be the most expensive local park in U.S. history. (About $200 million of the cost was covered by the George Kaiser Family Foundation, while the city, as well as other foundations and businesses, picked up the rest.)

All programs are free. Chief among them is Global Gatherings, a 13-week program that last year featured weekly events highlighting traditions from more than a dozen regions of the world—Southeast Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, Native America, and others. The program drew nearly 4,500 people and involved more than 80 community partners in activities that featured food, music, dance, traditional attire, storytelling, and crafts.

“Global Gatherings is a collaborative celebration of cultures, and we were ecstatic with the community’s response to the multi-week program,” said Julio Badin, executive director of Gathering Place. “Tulsans of all global backgrounds gathered at the park to share and highlight their traditions to immerse other community members in their rich cultures through art, storytelling, food, music, and dance.”

Jacque Riggs, a jewelry designer and silversmith, arrived in Tulsa from Peru in 2002. Last summer, Riggs and her daughter, Zadith Rodriguez, a 28-year-old printmaker, participated in Global Gatherings. Riggs, 50, helped children make bracelets from brightly colored huayruro seeds. Such bracelets are considered protective amulets, given to newborns to ward off evil spirits. Zadith, for her part, showed children how to make prints of llamas and mountain scenes using paper and inks. There was even a map of Peru.

“It’s always nice to be able to talk a bit about your culture,” Riggs said. “The children were excited and seemed really interested in what we were doing. I also took some bracelets to people at the festival who were from Brazil and Venezuela and said, ‘Hey, I want to give this to you for good luck.’”

Park leaders across the country report employing partnerships with organizations that deliver park stewardship (74), arts and culture (61), public health (55), and literacy (45) programming. But partnerships that leverage green spaces to address underlying community- level challenges like housing stability (15) and immigrant inclusion (22) are relatively scant (Table 4).

An emerging group of cities report fostering partnerships between park professionals and outside agencies in order to offer a wider array of programming and resources, such as English-as-a-second-language classes, mindfulness workshops, and job training.

Trust for Public Land examined the connection between a city’s ParkScore ranking and two key indicators of social capital, including volunteerism rates . Parks systems that create and facilitate opportunities for residents to volunteer in their communities can contribute to greater cohesion among neighbors . Photo: Justin Bartels

Table 4

Data source: 2024 TPL City Park Facts Survey of all public and private park organizations across the 100 most populous cities. The counts reflect the number of cities with at least one organization reporting the given activity.

Trust for Public Land research indicates that parks departments should engage residents at every phase of park development, from design to programming. Such was the case at San Geronimo Commons, a former golf course turned community green space in California. Photo: Kevin Quach

CONCLUSION: Community on the Cusp — What Can Be Done

Parks hold tremendous potential for repairing our frayed social fabric, making it incumbent upon the entire parks and recreation field, as well as nonprofit and philanthropic organizations, government agencies, the private sector, and private citizens, to lean into funding and programming opportunities.

The following strategies can optimize the power of parks to elevate social connectedness.

At the local level: Prioritize community engagement. This must be a priority, included in master plans and set forth in local park policy. The process of reaching out to residents and cultivating relationships takes time and intention, so local governments need to dedicate adequate resources in the form of staff, money, and training.

Parks departments should engage residents at every phase of park development, from the spark of an idea for a new park to the creation of park-based programming. This can happen through a one-time design workshop, for example, or through an advisory council or planning committee that meets for months or years. Park professionals should also make full use of friends groups and help establish new ones in under-resourced neighborhoods. And they should consider compensating resident liaisons.

The TPL survey found evidence that there’s a strong public will for funding these efforts. Parks budgets were up across the board in the past year. Total public and private spending on parks and recreation in the 100 most populous cities climbed to $11.2 billion, up from $9.7 billion in 2022 and $8.7 billion five years ago.

At the federal level: Park advocates, administrators, and users can support the Outdoors for All Act (O4A). Among other things, O4A would improve the Outdoor Recreation

Legacy Partnership (ORLP), a grant program run by the National Park Service that provides funding for communities that need parks the most. Specifically, the legislation, which TPL is championing in Congress, would make ORLP permanent, avoiding the need to renew the program annually. If passed, the bill would also allow federally recognized tribes to apply to the funding program for the first time, while letting tribes, cities, and nonprofits apply directly to the National Park Service (instead of having to go through their state governments). Finally, the legislation would lower the population requirement to 25,000, meaning smaller cities and towns would be eligible for funding.

“One thing our research reveals is that parks are among the best places to foster community and safeguard democracy,” says TPL Community Strategies director Cary Simmons. “The fact that parks and public spaces are neutral makes them very strategic for investing your time or energy or philanthropic dollars if you want to see a community overcome division.”

Trust for Public Land is working in close collaboration with several partners, city officials, and community groups on a new park on a former brownfield in San Francisco. When completed, the 10-acre India Basin Waterfront Park, in the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood, will offer boat access, as well as walking and bike paths, an extensive picnic area, basketball courts, playgrounds, restrooms, a food pavilion, a history museum and community center, lawns, piers, and a floating dock. The park also features restoration of wetlands, expansion of wildlife habitat, and naturalization of the waterfront edge. The park was designed with extensive community input and will protect residents from sea level rise, as well as offer needed resources.

The park is emerging in an area that, from the 1850s to the 1900s, thrived as its shoreline was used as a civilian and military shipyard and slaughterhouse. Those industries, now defunct, left significant environmental damage, however, impacting the land and cutting off residents from the waterfront. The neighborhood, which is one of the few remaining historically Black neighborhoods in San Francisco, has also suffered from deep neglect of basic infrastructure and generations of social injustice.

The goal in developing the new park is as much to create a spectacular new green space as it is to strengthen the neighborhood—economically, socially, and politically. To achieve that, an Equitable Development Plan informs every aspect of the project and was developed by the community and the four project partners: TPL, the San Francisco Parks Alliance, the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department, and the A. Philip Randolph Institute. Local residents receive training in construction jobs through a robust workforce development program. And a tech hub within the park is now providing free Wi-Fi, loaner laptops, and tech support, even before the park’s official opening.

The vision for India Basin Waterfront Park, when completed, calls for a diversity of programming to strengthen the community’s bonds. Dr. Han said that without such programming, fleeting interactions in parks—a quick greeting, say, or a remark about someone’s dog—are missed opportunities.

Contributors

Tim Almaguer, Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks, Community Engagement and Strategic Partnership Division | Julio Badin, Gathering Place | Melissa Rhodes Carter, Walmart Foundation | Howard Frumkin | Dr Hahrie Han, Johns Hopkins University | Linda Hwang | Will Klein | Hannah Kohut | Keith Maley | Dara Murray | Kevin Niu | Cary Simmons | Sherry Taylor | Diane Regas | Jacque Riggs | Andrea Roberts, East Baton Rouge Parish Parks and Recreation Department (BREC) | Levar Robinson, BREC Community Advisory Council | Zadith Rodriguez | Geneva Vest | Šárka Volejníková | Dan Walsh | Deborah Williams

Across the United States, people are divided by politics, economics, race, ethnicity, and ideology. A looming presidential election and contentious wars abroad have raised those tensions further.

Across the United States, people are divided by politics, economics, race, ethnicity, and ideology. A looming presidential election and contentious wars abroad have raised those tensions further.