More than 2,000 miles separate two iconic mountain landscapes that Trust for Public Land recently protected, and in many ways, the properties could not be more different. Fishers Peak—in Trinidad, Colorado, on the New Mexico border—was long a private game-hunting reserve, rising above an old mining town in the arid Southwest. With rocky ledges and stands of pinyon, it teems with elk, mule deer, and mountain lions. On the other side of the country, deep in the dense forests of Central Maine, Moxie Bald Mountain lies far from any human habitation, surrounded by timberland and sparkling lakes that draw moose, Canada lynx, and bobcats.

More than 2,000 miles separate two iconic mountain landscapes that Trust for Public Land recently protected, and in many ways, the properties could not be more different. Fishers Peak—in Trinidad, Colorado, on the New Mexico border—was long a private game-hunting reserve, rising above an old mining town in the arid Southwest. With rocky ledges and stands of pinyon, it teems with elk, mule deer, and mountain lions. On the other side of the country, deep in the dense forests of Central Maine, Moxie Bald Mountain lies far from any human habitation, surrounded by timberland and sparkling lakes that draw moose, Canada lynx, and bobcats.

But in other important respects, the mountains bear striking similarities. Both were beloved by local residents who for decades had sought their protection. Both were privately owned yet accessible to the public—though that access ranged from minimal and tricky, in the case of Fishers Peak, to broad and effortless, in the case of Moxie Bald Mountain. Finally, the two mountains are now forever protected: rewarding adventurers with spectacular views from their respective summits, connecting to adjacent conservation lands, preventing development, and guaranteeing access in perpetuity.

Protected access is crucial. Even though hikers could cross through the properties, there was no assurance that a future owner would have the same laissez-faire attitude. Often, such informal access vanishes when a property changes hands and a new owner no longer wishes to share it. Fishers Peak itself was hit or miss: “The former owner did allow access to climb the peak on occasion, but she was kind of fickle,” explains Tim Crisler, an ardent hiker who helped found the Facebook group Trinidad Trails, with more than 2,000 members. “It wasn’t difficult to get permission, but it wasn’t easy. You always had to sign a waiver.”

Protected access is crucial. Even though hikers could cross through the properties, there was no assurance that a future owner would have the same laissez-faire attitude. Often, such informal access vanishes when a property changes hands and a new owner no longer wishes to share it. Fishers Peak itself was hit or miss: “The former owner did allow access to climb the peak on occasion, but she was kind of fickle,” explains Tim Crisler, an ardent hiker who helped found the Facebook group Trinidad Trails, with more than 2,000 members. “It wasn’t difficult to get permission, but it wasn’t easy. You always had to sign a waiver.”

Here’s a look at how conservation of the two mountains unfolded, with help from local partners, government agencies, and a bit of luck.

Rising some 3,000 feet over the city, Fishers Peak has always loomed large for Trinidad, a city of over 8,000 people. It would be an understatement, in fact, to say the distinctive flat-topped peak is the city’s symbol, given that it figures in business logos and artists’ renderings. But until its protection , only the most determined outdoors people, such as Crisler, had ever made the ascent, which tops out at 9,633 feet above sea level.

Wade Shelton, a senior project manager with Trust for Public Land, started to explore protecting Fishers Peak nearly a decade ago. Conservation of the mountain, which is a three-hour drive from Denver, was running into resistance. “When I first started looking at the property in 2014, there was no way for the state of Colorado to buy more land for state parks,” Shelton says. “So originally, we were going to transfer it to Trinidad.”

But after Trust for Public Land partnered with The Nature Conservancy to acquire the enormous property, containing 19,200 acres (or 30 square miles), politics shifted and the impossible suddenly seemed possible. “Once we bought and held it with The Nature Conservancy, the logic of it becoming a state park became very evident,” Shelton adds, “and the governor agreed.”

In early 2020, the land was conveyed to Colorado Parks and Wildlife; that fall, Fishers Peak State Park opened to the public, albeit with a limited trail network. Work is now underway to extend those trails. Despite the fact that the former reserve had 60 miles of roads for big-game hunting, most were not suitable for hiking trails and are being restored to their natural state.

– Tim Cresler, Trinidad, Colorado, resident

Crisler says that even though the state park remains a work in progress, the feeling among hikers and recreationists is one of overwhelming relief. “This is a huge thing for people here,” he notes. “The overall sentiment is absolute ecstasy—like, ‘Oh my god, this finally happened in our lifetime and now it’s open to the public.’ I can’t wait to be able to take my friends from Denver on a hike up there.”

A resident of Trinidad for more than 20 years, Crisler has climbed all 55 peaks in the state of Colorado that exceed 14,000 feet. Of Fishers Peak, he says: “It’s not an easy climb. This mountain takes a long full day of hiking, from the bottom to the top and down again. And there are places on it that are scary, that are exposed.”

But the payoff is considerable: “Once you get up there, the top is just a big, open, flat area, and in the springtime and summer, it’s covered with wildflowers,” says Crisler, referring to the signature mesa on the summit. “And there’s an amazing view. To the north and northwest, you see all the way to Pikes Peak and the Spanish Peaks; to the west, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and, to the south, Raton Mesa.”

But the payoff is considerable: “Once you get up there, the top is just a big, open, flat area, and in the springtime and summer, it’s covered with wildflowers,” says Crisler, referring to the signature mesa on the summit. “And there’s an amazing view. To the north and northwest, you see all the way to Pikes Peak and the Spanish Peaks; to the west, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and, to the south, Raton Mesa.”

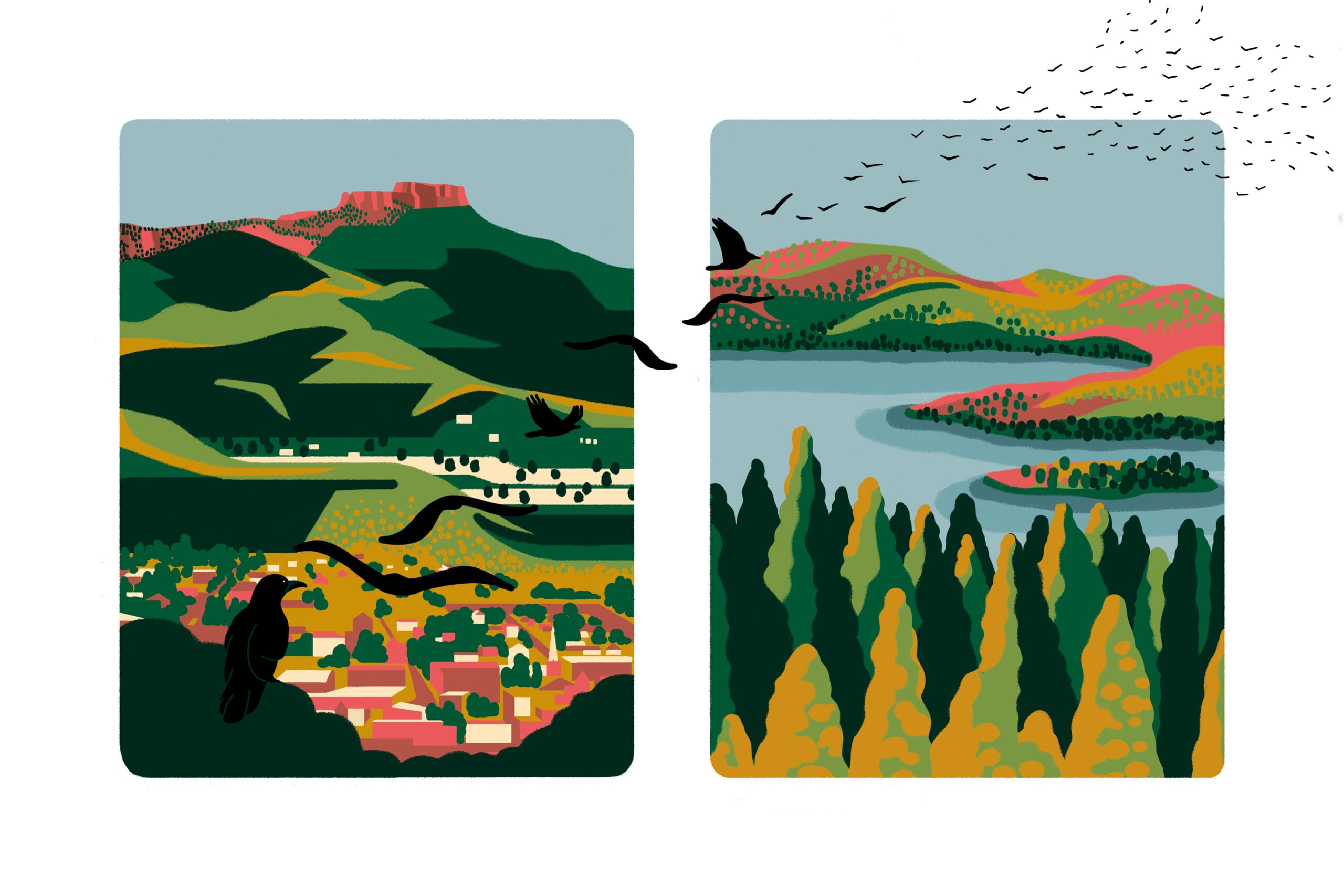

Purchase of the property had something of a multiplier effect for conservation in the Mountain West region. Two protected properties—the Lake Dorothey and James M. John State Wildlife Areas—extend along the eastern edge of Fishers Peak State Park in Colorado. Immediately to its south, in New Mexico, is Sugarite Canyon State Park. “When you add those properties to Fishers Peak, then it’s 50 square miles of protected land,” Shelton points out.

Trinidad’s mayor, Phil Rico, says the new state park has the potential to put Trinidad on the outdoor recreation map. “We believe the city of Trinidad is going to develop into a destination area,” he says. “We have a river that runs right through our community, and we are working to develop the whole outdoor recreation sector. One study that looked at the potential said we could get 50,000 to 100,000 tourists annually, with an economic impact of $12 million a year.”

For Shelton, making sure Trinidad derives all the benefits from the newly protected Fishers Peak is paramount. Indeed, Trust for Public Land remained on the scene after the conservation deal, helping the city draft a recreation management plan. “We want to set up our municipal partners so they can take advantage of the park to catalyze the economy,” he explains.

“The city is going to need physical infrastructure like hotels, restaurants, bars, and parking—things that keep tourists around,” Shelton adds. “To create a diverse economy, Trinidad will also need human infrastructure, so that people can live and work there. The idea is to create a playbook other rural communities can look at and say, ‘How can we take the lessons of Fishers Peak and apply them here?’”

In the end, meaningful change for Trinidad will, hopefully, translate into successes for similar areas, which means greater access to nature for more people—the long game TPL is continually playing (and, in many cases, winning).

Feeling inspired? These places—and many more—are protected thanks to Trust for Public Land supporters. Join us in our mission to bring the profound benefits of equitable access to the outdoors to millions of people across America.

Ten states and two time zones to the northeast, in Bald Mountain Township, Maine, the concern was less about generating commercial activity than keeping it at bay. The Appalachian National Scenic Trail runs along the property at Moxie Bald Mountain that Trust for Public Land recently helped protect. And like many areas around the trail, especially in Maine, development and industrial-scale timber harvesting have crept closer in recent decades.

According to Simon Rucker, executive director of the Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust, the Appalachian Trail (AT) was laid out starting in the late 1920s. The portion in Maine was protected via “handshake deals” with timber companies. But in 1968, the federal government appropriated funds to the National Park Service to buy the trail. There was only enough money to acquire a strip of land, however. “Down south, the AT goes through Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” Rucker says. “In Maine, there is very little of that kind of protection. A lot of the trail is 500-feet wide, just a corridor.”

According to Simon Rucker, executive director of the Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust, the Appalachian Trail (AT) was laid out starting in the late 1920s. The portion in Maine was protected via “handshake deals” with timber companies. But in 1968, the federal government appropriated funds to the National Park Service to buy the trail. There was only enough money to acquire a strip of land, however. “Down south, the AT goes through Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” Rucker says. “In Maine, there is very little of that kind of protection. A lot of the trail is 500-feet wide, just a corridor.”

Such was the case in Somerset County, about three and a half hours north of Portland by car. For years, various timber companies had owned several hundred thousand acres of forest there. But conservationists set their sights on a 2,600-acre corner of the vast timberland, which included the majestic Moxie Bald Mountain, as well as Bald Mountain Pond, and a stretch of the Appalachian Trail that crosses over the summit.

J.T. Horn, director of Trust for Public Land’s national Trails initiative, first learned about Moxie Bald Mountain in 2002 when he was with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is really cool,’ but it wasn’t the right moment,” he recalls. “The timber company that owned it at the time wasn’t ready to sell.”

Fast-forward a dozen years, and the owner was receptive to a conservation deal. The forest surrounding the trail, along with Bald Mountain Pond, had long been available to hikers and paddlers through an informal agreement. But future access wasn’t assured. “It’s a classic Maine adventure—a paddle-hike combination,” Horn points out. “It’s not for the faint of heart. It is a wilderness experience, and it’s way out there. But it’s also one of those experiences that really makes your jaw drop.”

It’s a classic Maine adventure . . . one of those experiences that really makes your jaw drop.” – J.T. Horn, Trust for Public Land’s national Trails initiative director

In 2020, Trust for Public Land announced the permanent protection of more than 2,620 acres of land at Bald Mountain Pond. The conservation deal included three phases—and three different owners. The National Park Service assumed ownership of 1,356 acres of the mountain. The Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust took possession of more than 1,000 acres around the pond, including 9 miles of shoreline. And the state of Maine acquired acreage at the pond’s southern tip, where there is now a parking area and boat launch.

Conservation of the property created an important buffer along 5 miles of the AT and guaranteed public access to Bald Mountain Pond via private logging roads. To access the pond, you either need to be a thru-hiker on the Appalachian Trail—the nearest paved road is days away on foot—or strap a kayak to an all-wheel drive vehicle and navigate the logging road.

Conservation of the property created an important buffer along 5 miles of the AT and guaranteed public access to Bald Mountain Pond via private logging roads. To access the pond, you either need to be a thru-hiker on the Appalachian Trail—the nearest paved road is days away on foot—or strap a kayak to an all-wheel drive vehicle and navigate the logging road.

Either way, the experience is remote, wild, and pristine. “You are on a dirt road that’s in pretty rough shape for 15 miles to reach Bald Mountain Pond,” Rucker says. “That’s an area where there are still active logging operations. But the conservation land forms enough of a buffer, so that when you’re on the pond, you don’t hear any of that.”

A day trip might include kayaking or canoeing north across the pond, which is home to landlocked Arctic char. At the opposite shore is a lean-to, near where you can pick up the Appalachian Trail for the 2,630-foot climb up Moxie Bald Mountain. The hiking app AllTrails describes the 4-mile out-and-back trail as “moderately challenging,” adding that “it’s unlikely you’ll encounter many other people while exploring.”

“From the top, you can see the Bigelow Range, Sugarloaf and Saddleback Mountains, and the 100-Mile Wilderness,” Rucker notes. “When you are up there on a clear day, you can see well into Canada. And then you hike down and get back in your canoe and you can be home by dinner.”

In addition to identifying sources of public money for the conservation project, Trust for Public Land helped raise private funds. Support came from the National Park Trust, the National Park Foundation, and the Elliotsville Foundation, among others.

Lucas St. Clair is president of the Elliotsville Foundation, which focuses on conservation in Maine. He describes Moxie Bald Mountain as a classic northern hardwood forest, with fir and spruce mixed in. “It’s a great trail,” says St. Clair, who also chairs Trust for Public Land’s National Board of Directors. “You see evidence of moose, and there are Canada lynx and bobcats and a whole host of songbirds, especially if you are there in the spring during migration.”

In the late 1990s, St. Clair and his twin sister hiked the length of the Appalachian Trail, from Georgia to Maine. (Tellingly, the AT’s first full thru-hiker was a World War II veteran seeking to “walk off the war,” a testament to nature’s healing power.) “Maine is one of the most wild places along the whole stretch, where you really feel like you are in wilderness,” explains St. Clair. “But there are subtle reminders that you are hiking through industrial forestland. You cross logging roads and you hear machinery and pulp trucks in the distance. Not that we are opposed to forestry, but it can feel disorienting when you are there for an outdoor wilderness experience.”

His family foundation (started by St. Clair’s mother and Burt’s Bees cofounder, Roxanne Quimby) has devoted its resources to preserving a sense of wilderness, protecting some 20,000 acres along the AT in Maine. The foundation gave $1.1 million, for instance, toward conservation of Moxie Bald Mountain. “We work to protect the AT’s treadway and the experience for thru-hikers, but also to provide access points,” he says. “The majority of users of the Appalachian Trail are not thru-hikers, but people who are experiencing it somewhere along the way.”

For TPL, the project at Moxie Bald Mountain was the latest in a string of conservation efforts along the Appalachian Trail. Trust for Public Land has completed more than 140 such projects, protecting 310,000 acres. The Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust had described Bald Mountain Pond as the highest priority conservation project on the AT in Maine.

“The whole reason why people fall in love with the Appalachian Trail extends far beyond the narrow footpath,” Horn says. “Where you have this old-growth forest, these big views and these big lakes, expanding the buffer of protected area is really important so that people can immerse themselves in wilderness.” Now, thankfully, such wilderness experiences are protected indefinitely in Colorado and Maine.

Lisa W. Foderaro is a senior writer and researcher for Trust for Public Land. Previously, she was a reporter for the New York Times, where she covered parks and the environment.

Bea Crespo is an illustrator based in Barcelona. She loves creating drawings with various meanings, representing things that surely exist—although we may not be able to see them.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.