Historian Alison Rose Jefferson on the generations-long fight for belonging at one Southern California beach

Historian Alison Rose Jefferson on the generations-long fight for belonging at one Southern California beach

This Earth Month, we’re highlighting people who are speaking up and fighting for equitable access to the outdoors—something that historian Alison Rose Jefferson knows a lot about. Her research, writing, and activism have focused on the ways Black people have fought against generations of discrimination and exclusion for their rights to use public spaces and connect with the natural world.

For Jefferson, and for the many people whose stories she explores in her book Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, access to outdoor recreation is about much more than relaxation. She writes that the places where Black people have historically gathered outdoors should be remembered as “places of commerce, social networks, community, identity, contestation, and civil rights struggle.”

We’re proud to work with Jefferson and other experts and leaders in the movement to lift up a more accurate and equitable history of the nation through The Trust for Public Land’s Black History and Culture Advisory Council. We caught up with Jefferson, who is a member of the council, to learn about the generations-long fight for belonging and representation at one Southern California beach, and how that history is still shaping our experience and understanding of the place today.

Historian Alison Rose Jefferson has researched, written about, and advocated for the public commemoration of Black beachgoers in Southern California during the Jim Crow era.Photo credit: Courtesy Alison Rose Jefferson

Historian Alison Rose Jefferson has researched, written about, and advocated for the public commemoration of Black beachgoers in Southern California during the Jim Crow era.Photo credit: Courtesy Alison Rose Jefferson

You’ve researched, written about, and advocated for a spot called Bruce’s Beach, in the city of Manhattan Beach, California. What drew your interest about this place?

Willa Bruce and her husband, Charles, moved to Southern California sometime between 1900 and 1910. They were part of a wave of people relocating to California, in part for the climate and what its great outdoors had to offer. African Americans in particular, like the Bruces, were also arriving in California looking to get away from anti-Black racism they were facing elsewhere in the country, seeking employment and better social conditions.

In 1912, the Bruces opened a small resort on a piece of beach front land in Manhattan Beach. Initially it was a pretty simple affair: some pop-up tents where refreshments were served and where people could change clothes. Eventually they added a dancehall, a pavilion, a home for themselves, and a few places for overnight guests. By the early 1920s, Bruce’s Beach was a pretty happening place. Black people from all over the Los Angeles region were coming there to enjoy the beach, and the Bruces were making a livelihood from creating this space where Black Angelenos could enjoy the fruits of their labors and everything California’s outdoors has to offer.

Sweethearts Margie Johnson and John Pettigrew at the crowded Pacific Ocean shoreline in 1927. This photograph and others at Bruce’s Beach were featured on a page in the scrapbook of LaVera White who lived in Los Angeles for most of her life.Photo credit: from the private LaVera White Collection of Arthur and Elizabeth Lewis featured in Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, 2020 by Alison Rose Jefferson.

Sweethearts Margie Johnson and John Pettigrew at the crowded Pacific Ocean shoreline in 1927. This photograph and others at Bruce’s Beach were featured on a page in the scrapbook of LaVera White who lived in Los Angeles for most of her life.Photo credit: from the private LaVera White Collection of Arthur and Elizabeth Lewis featured in Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, 2020 by Alison Rose Jefferson.

What kinds of discrimination did the Bruces and their guests have to endure?

From the first days of their resort, the Bruces faced discrimination and conflict from their white neighbors. A nearby property owner named George Peck got constables to patrol the public beach to keep resorts guests from using the ocean. The town passed ordinances limiting parking near the resort to one hour, or banned changing clothes in your car. People had their tires slashed—there were years and years of harassment.

[Read more: When a fight to “free the beaches” rippled beyond the coast.]

In the early 1920s, the press and white neighbors used the term “Negro invasion” to describe their campaign against the Bruces and their guests using space in Manhattan Beach. It was a phrase used all over the country during the Jim Crow era to talk about African Americans who—despite harassment and discrimination—were asserting their rights to enjoy the fruits of American society.

What became of Bruce’s Beach resort?

By 1924, white residents of Manhattan Beach got the city council to seize the Bruce’s land and that of other African American families through eminent domain—ostensibly to create a public beach park at the site. By 1925 the city had razed everything the Bruces and other Black landholders had built. Still, Black residents and visitors kept asserting their rights to use the public beaches that their tax dollars were funding. In 1927, the local chapter of the NAACP even staged a wade-in, where a dozen protestors entered the water in an area where a white property lessor had illegally posted “No Trespassing” signs. It was the first organized action of civil disobedience by the Los Angeles chapter of the NAACP.

What was the outcome of the protest?

Police arrested protestors and four were eventually charged with resisting arrest and disturbing the peace. But during the proceedings it came out that the white resident who’d posted the “No Trespassing” signs had no legal right to do so, and affirmed that African Americans had the right to use this beach and any public beach in California. So it was a victory, from that standpoint. Of course, there had been laws as early as 1893 to protect public use of the beach, but those laws were typically not enforced for the benefit of Black people, so this case offered an important clarification and reinforcement of Black beachgoers’ rights.

[Read more: Explore 15 parks honoring Black history]

Bruce’s Beach was one front in the national mass movement to open recreational facilities and space to all Americans. People forget that discrimination has never just been about jobs and the economy. It’s in all aspects of life—even, or especially, free time, which is one of the most treasured parts of our lives.

From left to right, Mrs. Willa Bruce, with her daughter-in-law Meda and her sister enjoying the sunshine at the seashore near Bruce’s Lodge in Manhattan Beach, California, ca. 1920s.Photo credit: The California African American Museum Collection featured in Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, 2020 by Alison Rose Jefferson.

From left to right, Mrs. Willa Bruce, with her daughter-in-law Meda and her sister enjoying the sunshine at the seashore near Bruce’s Lodge in Manhattan Beach, California, ca. 1920s.Photo credit: The California African American Museum Collection featured in Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, 2020 by Alison Rose Jefferson.

What about the city’s plan to build a public park on the site of Bruce’s Beach?

The park plan was just a subterfuge to get African Americans out of the area. At the time, there were nearby beachfront lands that hadn’t yet been developed that the city could have seized if they really wanted to. What’s more, the town didn’t get around to building a park for another forty years. It wasn’t until the late 1950s that they did some landscaping and put in what was called Bayview Terrace Park, which is more or less what you see today.

Was the Bruces’ experience an outlier?

What happened to the Bruce family is part of a pattern that was repeated all over the country—a white supremacist mentality that attempts to legislate and discriminate against Black people enjoying themselves. During Jim Crow, some national parks had signs up separating areas white people could use from areas that Black people were supposed to use. So why would Black people want to visit those parks? Aside from not being welcome in these outdoor spaces, there’s was also the hurdle of travel to remote places being expensive, and of the lack of safety that Black travelers faced at the hands of white residents and law enforcement in remote areas.

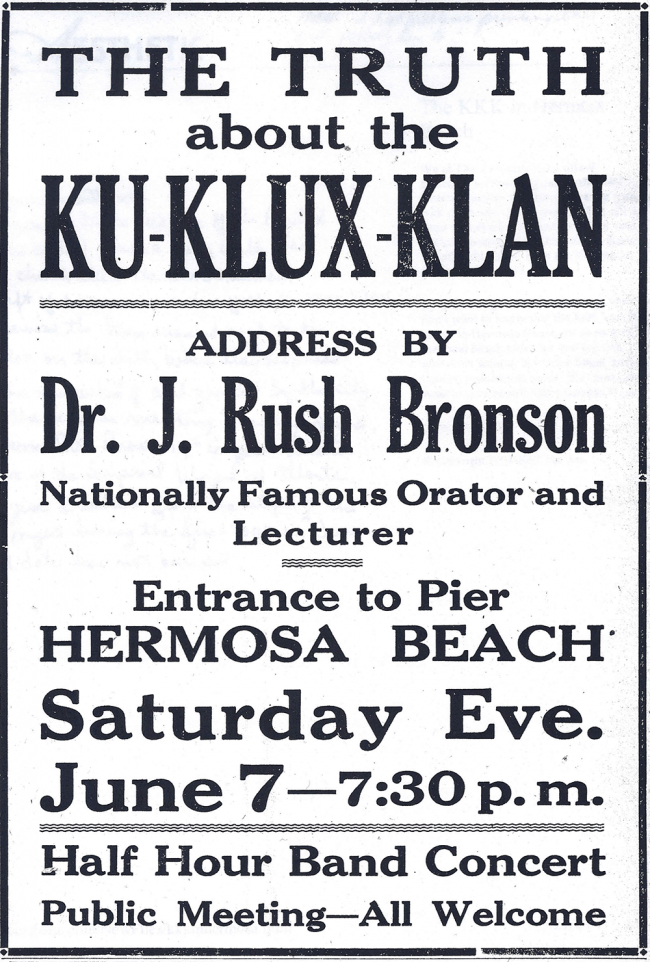

Klu Klux Klan meeting advertisement, Manhattan Beach News, June 6, 1924. An intimidation campaign was organized by the Klu Klux Klan, or at least their sympathizers, to terrorize the Bruces and other American Americans who visited Manhattan Beach.Photo credit: The Manhattan Beach Historical Society Collection featured in Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, 2020 by Alison Rose Jefferson.

Klu Klux Klan meeting advertisement, Manhattan Beach News, June 6, 1924. An intimidation campaign was organized by the Klu Klux Klan, or at least their sympathizers, to terrorize the Bruces and other American Americans who visited Manhattan Beach.Photo credit: The Manhattan Beach Historical Society Collection featured in Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, 2020 by Alison Rose Jefferson.

This history is important to keep in mind when you think about the makeup and lack of representation in the contemporary conservation movement. Black people were and still are excluded from outdoor spaces, and conservation organizations themselves have not been welcoming to African American participation.

You’re part of the effort to research and share the true history of Bruce’s Beach. What’s happened in recent years?

In the mid-2000s, a few Manhattan Beach residents launched an ultimately successful campaign to revive the name “Bruce’s Beach” for the park. I started researching the history of the area around then, and attended city council meetings in support of the name change. The city also put up a plaque at the time, but it misrepresents actions of white citizens, and doesn’t mention that the City seized the land from a successful Black business owner. So I’ve researched and been part of a group that’s working to get that story straight. I also have written op-eds about this issue for outlets like the Los Angeles Times. The Manhattan Beach City Council recently agreed to install new plaques that include a more accurate history of this park.

Bruce’s Beach is just one of the many places where Jefferson’s research, writing, and advocacy has made a difference. In 2019, she jointly led the campaign to get Santa Monica’s Bay Street Beach Historic District, long a favorite destination for Black beachgoers from around the Los Angeles region, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today she’s working alongside artists and community members to produce Belmar History + Art, a project that educates visitors and neighbors about Black life in South Santa Monica Beach neighborhoods in the first half of the 20th century.

[Keep reading: Preserving Black history for a more equitable future]

Meanwhile, a movement is growing to return Bruce’s Beach to Willa and Charles’s descendants. California State Senator Steven Bradford introduced a bill last week that would allow Los Angeles County to transfer the land to the Bruce family. “We stand here today to introduce a bill that will correct this gross injustice and allow the land to be returned to the Bruce family,” Bradford said. “It is my hope that this legislation will not be the last in a series of actions by the state to address centuries of atrocious actions against Black Americans.”

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.