Cavers crave the crazy-weird wilderness beneath your feet

Cavers crave the crazy-weird wilderness beneath your feet

Lisa Bauman-Cook has spent thousands of hours crawling, shimmying, scrambling, and rappelling into caves across the western United States. But do not call her a spelunker.

That term, she says, was coined by mid-20th-century tourism boosters to entice customers into caves. As a result, in today’s caving culture, “spelunker” has taken on an unfortunately onomatopoeic connotation: “It’s sort of a dark joke among us that ‘spelunk’ is the sound of the uninitiated falling into puddles on the floor of the cave,” Bauman-Cook says.

So Bauman-Cook is not a spelunker but a caver, part of a worldwide fellowship of people who explore and study caves safely and sustainably. She first set foot in a cave 15 years ago, on a weekend trip to the Lava Beds National Monument, near the California-Oregon border. The jagged, arid landscape here is shot through with dozens of lava tubes—remnants of ancient volcanic eruptions—and from her first step inside the cool subterranean chambers, she was sunk.

The Trust for Public Land has protected dozens of caves. At Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary near downtown St. Paul, a cave that the Dakota people call Wakan Tipi (Spirit House) gapes from a sandstone bluff.Photo credit: The Minnesota Historical Society

The Trust for Public Land has protected dozens of caves. At Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary near downtown St. Paul, a cave that the Dakota people call Wakan Tipi (Spirit House) gapes from a sandstone bluff.Photo credit: The Minnesota Historical Society

“Right away I became enamored with caves. I remember feeling such a powerful sense of wonder at discovering a whole hidden universe underground,” Bauman-Cook says. She picked up a guidebook by legendary caver Charlie Larson and spent the rest of the summer submerged in her new hobby, following Larson’s directions to dozens of caves in eastern Oregon. Along the way, she joined a local caving club—or “grotto”—and learned the ropes, venturing into increasingly challenging caves.

“Caves host extremely fragile geologic formations, plants, and animals,” Bauman-Cook says. “That’s part of their allure, but it means we have a special responsibility as visitors not to harm the cave while we’re there.” While the wilderness ethos advises travelers to “leave only footprints,” Bauman-Cook says good cavers strive to avoid even that: underground, without wind or weather to erase them, footprints can last eons.

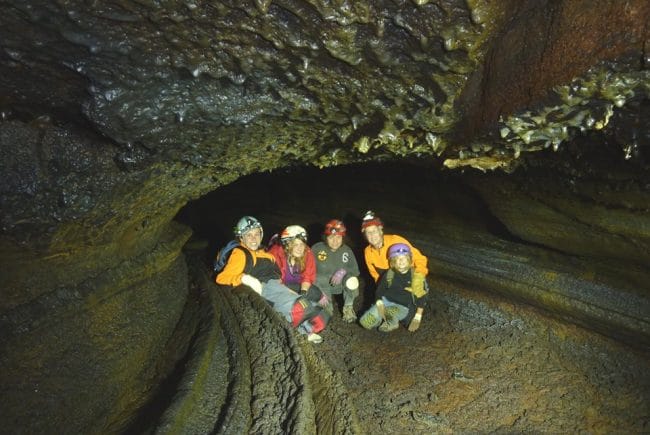

The National Speleological Society reports 45,000 known caves in the lower 48 United States. Caver Tabitha Rossman says that her local club in Oregon finds 6 to 10 new caves a year, “which gives you an idea of how many there are left to discover.” Photo credit: Lisa Bauman-Cook

The National Speleological Society reports 45,000 known caves in the lower 48 United States. Caver Tabitha Rossman says that her local club in Oregon finds 6 to 10 new caves a year, “which gives you an idea of how many there are left to discover.” Photo credit: Lisa Bauman-Cook

Bauman-Cook soon found herself one of the most active members of her local grotto. “I was visiting 30 caves a month. I was learning to conquer my fear of heights, to trust my skill—I was gaining confidence and seeing incredible, spectacular sights on every trip,” she says. Her favorite cave is studded with eight-foot-tall spires of cooled lava. The moisture in the cave has caused the rock to oxidize, so the formations, with gooey-looking fingers of rock protruding from all sides, are firey orange.

Undeterred by the cold, wet, dark, rough, muddy, and sharp conditions in the lava caves around the Northwest, Bauman-Cook has rappelled into deep caverns, hauled out less thoughtful visitors’ trash and debris, and spent 23 straight hours underground. She’s cast the light from her headlamp around caves bigger than a football field and squeezed through spaces barely large enough to admit her frame. And through all her adventures, she noticed a pattern: “I was typically the only woman in the cave.”

Bauman-Cook wanted to help more people—especially more women—tap into the same wellspring of confidence she’s been able to find in caving. So in 2010, she launched Extraordinary Women Leaders in Speleology (EWLS), a group that connects and supports women and girls interested in exploring underground. “It’s nothing against the men who’ve shared their knowledge and experience with me,” Bauman-Cook is quick to say—people of all genders are welcome on EWLS outings—but her passion is developing skills in women and other groups who are not well-represented in caving.

Lisa Bauman-Cook launched Extraordinary Women Leaders in Speleology to connect and support women cavers around the world.Photo credit: Ruth Stickney

Lisa Bauman-Cook launched Extraordinary Women Leaders in Speleology to connect and support women cavers around the world.Photo credit: Ruth Stickney

Tabitha Rossman is one caver who’s benefitted from Bauman-Cook’s drive to inspire others. “I learned about the group online and was so excited to find people to learn from,” she says. A wildlife biologist by training, Rossman takes her responsibility to protect the caves she explores seriously—for example, by preventing the spread of White Nose Syndrome, a deadly fungal infection that’s devastating U.S. bat populations from coast to coast.

“It’s important to decontaminate our gear between trips so we don’t risk transmitting the fungus to a healthy population,” Rossman explains. She has a professional interest in the weird wildlife that lives underground—from bats to salamanders and spiders—but even people who will never set foot in a cave have some good reasons to care about bats: they help control mosquitos and pollinate our crops.

The Trust for Public Land helped protect one of the largest bat colonies, or hibernacula, in the eastern United States: the abandoned Paddock Mine in New Hampshire.Photo credit: Ann Froschauer/US Fish and Wildlife Service

The Trust for Public Land helped protect one of the largest bat colonies, or hibernacula, in the eastern United States: the abandoned Paddock Mine in New Hampshire.Photo credit: Ann Froschauer/US Fish and Wildlife Service

Bauman-Cook and Rossman both say that if you want to get into caving, your first stop should be your local grotto. “The caving community is like one big family,” Rossman says. “We’ll be happy to have you and we love to share what we know with new cavers—as long as you’re not too claustrophobic!”

Among newbies and old hands alike, Bauman-Cook finds that the underground world tends to bring out the philosopher in people. “I talk to cavers all over the world, and time and again people say that being in caves makes them feel connected to something bigger. I feel it, too,” she says. Imagining a superheated subterranean river of magma boiling up from the belly of the earth … well, that has a way of putting things in perspective. “Caves make me feel like all my problems are tiny.”

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to pass the Outdoors for All Act to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.