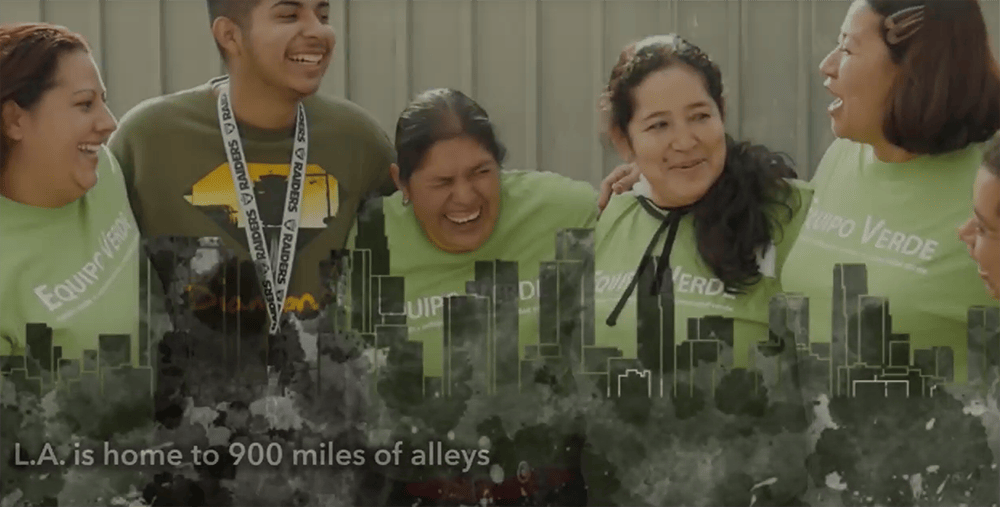

Sonia and the Equipo Verde turned a dangerous, polluted alleyway into their community’s source of pride.

By Amy Kunz

Published April 1, 2023

Potential is a matter of perspective. For decades, centuries even, the back alleys of most U.S. cities have been regarded as purely utilitarian service corridors where the less sightly aspects of daily life take place. It’s no wonder they’re often trash-strewn, unsavory, and even unsafe. That was the case in South Los Angeles until Sonia Rodriguez and the Equipo Verde (the Green Team) began to see themselves and these neighborhood passageways with fresh eyes.

Sonia, whose pride runs as deep as her family’s roots in South Los Angeles, realized the potential of a disregarded alley near her children’s school, where she worked as a parent coordinator.

“It’s the same school my husband and several members of his family went to, so it’s like history,” she explains. “That school has a legacy in our family and the community itself. And why not give back to what has given so much to us?”

The school’s principal at the time keenly understood the power of nature, of getting outside, and growing something from seed, Sonia says. “She was always making sure that the kids had a little bit of a grass to play on, an outdoor area, because we didn’t really have [safe] local parks nearby.”

Inspired by a small teaching garden that they had created and maintained on the campus with the principal, Sonia and other parents and grandparents began working on an urban forest project at the school with the L.A. Unified School District and the nonprofit TreePeople. And when they saw its impact, they expanded their lens to find opportunities elsewhere in the community. That’s when they learned about Trust for Public Land’s innovative Green Alleys project.

If you look at the west side of Los Angeles, you see trees, Sonia says. “But there’s nothing over here with us.” She adds that, while there was a park just two blocks from the school, gang and drug activity made it an unsafe and unwelcoming place. “It’s like someone else took over what belonged to the community.” To make matters worse, the alley—which they used to get to the school and to the only grocery store in the area—had become unsafe.

Sonia, who’d seen the school principal approach her teaching garden with the same attitude, encouraged others in the neighborhood to ask: “Why not our city? Why not our children? Let’s take back something that’s going to be there for the kids in the long term.” She adds that parents shouldn’t have to take the weekend off to take their kids to a faraway park, especially because some don’t have money for transportation.

That’s when Sonia and several other dedicated and concerned neighbors in South Los Angeles formed Equipo Verde. The group teamed up with Trust for Public Land and the L.A. Sanitation Bureau and made it their mission to create safer pedestrian routes by transforming—first one, and now many—unsightly, trash-strewn, dimly lit, dangerous alleys into clean, welcoming, art-filled walkways and community gathering places.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to pass the Outdoors for All Act to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities!

They started with a single mile-long alley in Avalon, where they cleaned up trash, discarded furniture and mattresses and even the occasional dead animal carcass. Then they placed permeable paver stones where there was only a dirt path and planted shrubs and other greenery along the alley’s edges to make the space more pleasant, more healthy.

Known as Green Alleys, these innovation projects not only add publicly accessible green space where there was none, they also capture and infiltrate stormwater into the local aquifer. And in a state where droughts linger, that’s welcome news.

Completed in 2016, the Avalon Green Alley served as a demonstration project; it showed what was possible and laid the foundation for three future Green Alleys that have now been completed in Pacoima, in the San Fernando Valley, and, South Los Angeles.

It also helped Sonia and her neighbors realize their potential to serve their community. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Equipo Verde’s network of leaders helped residents get hard-to-obtain essentials like food, water, masks, vaccines, and—arguably most important of all—accurate information to neighbors in need.

Dayana Molina, TPL’s community organizer of parks design and development in Los Angeles, remembers having the resources to secure supplies but admits that not as much of it would have been distributed so efficiently and into the hands of the people who needed it most without connected, trusted folks like Sonia and the Equipo Verde.

To ensure their neighbors were receiving and understanding information about the virus and the vaccine and learning how to recognize fear tactics and disinformation, Equipo Verde created a text group on WhatsApp. Sonia remembers that Molina helped the team sort through the chaos on social media and in the news. “She would always tell us, ‘Trust the 311 source.’ She would say, ‘If it doesn’t come with the city logo, do not trust it.’”

For all they did for the community, the Equipo Verde volunteers say the alley project also did a lot for them. “The alley brought a lot of resources to the community,” says Sonia. “It gave us all these connections and resources that we didn’t know were out there.” She notes that some of the volunteers have since become leaders in other organizations, including herself. Molina introduced Sonia to the Urban Peace Institute, where she is part of the 2022 Leadership Institute cohort.

And now, thanks to those connections and their commitment to making their community stronger, Sonia and the Equipo Verde have an even longer, broader perspective. They’re looking well beyond their own backyards, so to speak.

In 2014, Equipo Verde and other community leaders from the area made their case with the L.A. City Council to get approval to redesign a public alley into a pedestrian mall. Two years later, they traveled to the state capitol in Sacramento to speak with lawmakers about parks and open space and addressed county leaders supporting a water conservation measure. And in 2019, Equipo Verde members testified before the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors in support of directing more funding from a countywide parks bill to South Los Angeles, where far too few people have access to a park close to home.

“Neither Sonia nor the Equipo Verde members see themselves as leaders, or at least they won’t admit it,” says Molina. “They are too humble, and in many ways, this is why the group continues to grow. They are experts, but they don’t flaunt it, and I think this is why Equipo Verde, since 2012, continues to be a force for good and change.”

Although Sonia and the team are proud of what they’ve been able to accomplish at the state level, it’s the hyperlocal earth-shifts happening right outside their back doors as a result of the Green Alley that mean the most. She recounts a story about a family who lived on the alley years before its transformation. After the father was killed in a gang-related incident in front of the house, the family moved away, but his daughter continued attending the local elementary school. At first reluctant to allow the girl to join a school-sponsored field trip to the Green Alley, her grief-stricken mother changed her mind after Sonia reached out personally to the girl’s uncle and, through him, convinced the mother it would provide an opportunity to heal, to do something positive, and to turn a place of fear and grief into a place of hope.