The Delaware River’s revival

The Delaware River’s revival

The Delaware River, the longest free-flowing waterway east of the Mississippi, meanders more than 300 miles from the Catskill Mountains in New York to Delaware Bay. Along the way, it serves as a major port, provides drinking water to 13 million people, and beckons hikers, kayakers, and birders. But it wasn’t always this way.

By the early 20th century, the river was so filthy that it stained the hulls of boats a dark brown and sickened visitors just from its stench. Dead zones were devoid of fish and other aquatic life. But thanks to a remarkable turnaround, American Rivers this spring named the Delaware its River of the Year for 2020. The organization credited tougher environmental laws and collaboration among government agencies and nonprofit groups for the decades-long transformation.

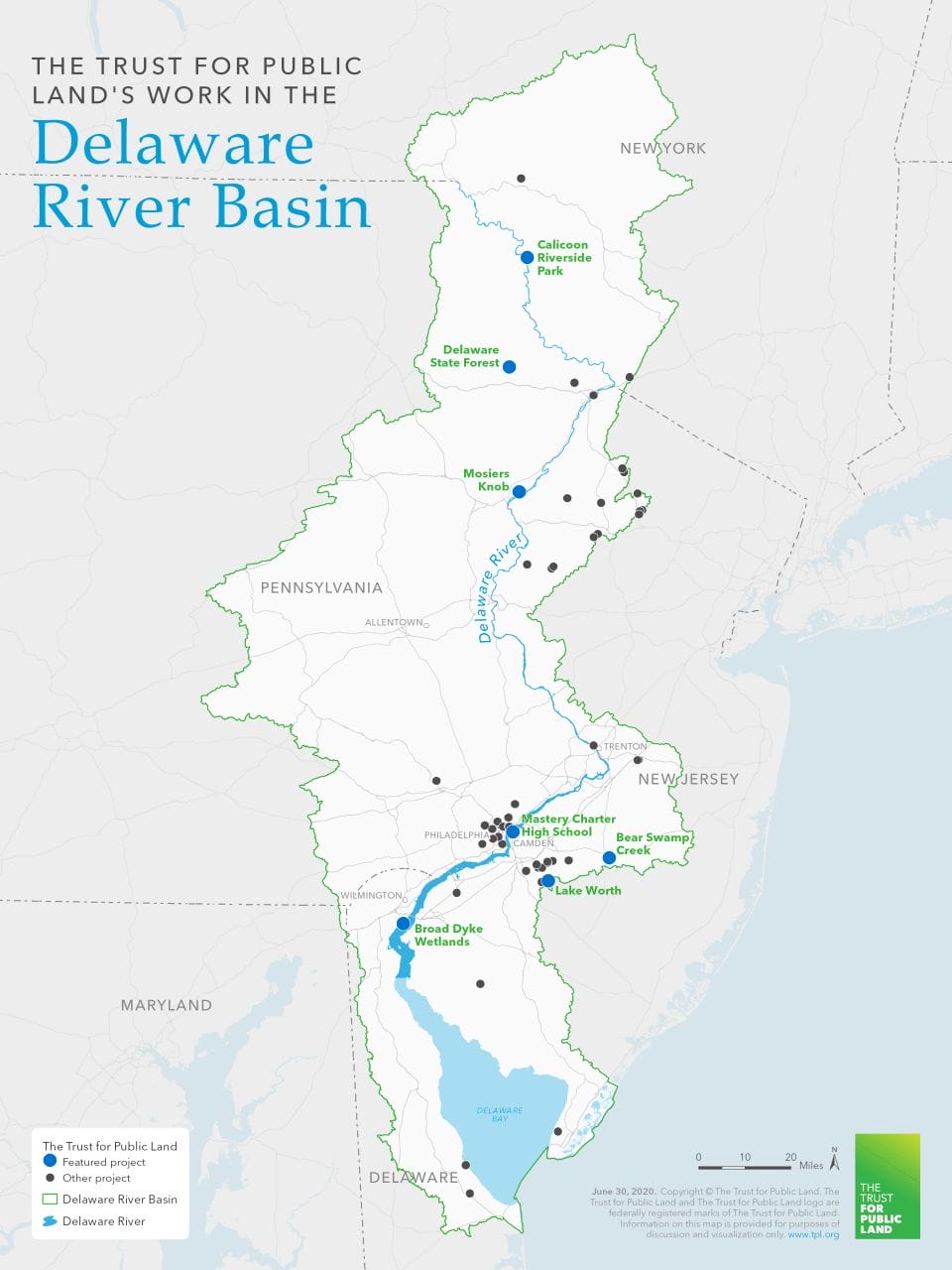

The Trust for Public Land is proud to have had a hand in the Delaware’s rebirth, protecting hundreds of acres of land in more than a dozen locations. We have built parks along the river’s banks and conserved land in the river’s 14,000-square-mile basin. Land protection is key to improving water quality, as it stanches the flow of stormwater runoff and other pollutants.

We’ve created more access to the outdoors, and preserved land that keeps water cleaner, throughout the Delaware River Basin. Photo credit: The Trust for Public Land

We’ve created more access to the outdoors, and preserved land that keeps water cleaner, throughout the Delaware River Basin. Photo credit: The Trust for Public Land

Here are just a few of the Delaware projects we have led or partnered on in the watershed.

Lake Worth

In 2001 we launched an initiative to create a 70-mile greenway in southern New Jersey, extending from the Delaware River in the city of Camden to Barnegat Bay next to the Atlantic Ocean. That same year, we negotiated the purchase of a 43-acre property in Camden County that includes Lake Worth, a longtime private bathing beach that had ceased operation in the late 1980s and had been drained of its water.

Located within the Delaware River basin, the property was then turned over to the Camden County Parks System, officially becoming a county park. Lake Worth, as the park is called, was one of the parcels identified for protection under the multi-use River to Bay Greenway, which provides connections to existing parks, creates new parks, and conserves land.

Callicoon Riverside Park

Situated on the Upper Delaware River, the town of Callicoon, New York, is blessed with natural beauty: mountains, farmland, forests–and, of course, the river itself, which teems with trout. But as in many rural areas, much of that landscape is privately owned, and therefore off limits.

We’re trying to rectify that by building a new riverfront green space, to be called Callicoon Riverside Park. The 48-acre tract, in northwest Sullivan County, currently houses a rundown RV park that suffered severe flood damage during Hurricane Irene in 2011. We are now embarking on an ambitious public process with the town, county and state to transform the neglected property. When completed, the park, with 4,000 feet of river frontage, will include a boat launch and more than two miles of trails. It will be one of the first parks in Sullivan County with direct access to the Delaware River.

The park project will also improve water quality in the Delaware by relocating a nearby wastewater treatment plant to higher ground. (The plant can flood.) Native plants will replace invasive species, absorbing stormwater runoff.

Photo Credit: Steve Aaron Photography

Photo Credit: Steve Aaron Photography

Green Schoolyard at Mastery Charter High School

In a green schoolyard project right on the banks of the Delaware River in New Jersey, we are working with students and staff at Mastery Charter High School in the city of Camden to transform the 11-acre campus into an inviting and ecologically friendly green space.

The project is one of our first green schoolyard renovations aimed at a high school—most involve elementary and middle schools. This year, the Mastery Charter community will have the chance to contribute ideas for the design so the schoolyard expresses the recreational needs and desires of students and local residents.

Among the considerations for the project are solar panels on the school’s roof, as well as green infrastructure to soak up stormwater and pollutants that would otherwise enter the two rivers converging at the school—the Delaware and its tributary, the Cooper River. When completed, the schoolyard will also serve as a green jobs incubator, providing skills and training to prepare interested students for careers in solar energy, ecology and environmental sciences.

Read more about our ongoing work and see detailed maps of our projects in Camden and Philadelphia.

Mosiers Knob

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, which straddles the Delaware River on the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border, draws millions of visitors a year to its mountains, ravines, beaches, and waterfalls.

In 2009, 550 acres of land in Smithfield Township, Pennsylvania, known as Mosiers Knob, was slated for 200 new residential units. The planned development, adjacent to the Water Gap, threatened not only the river’s water quality, but scenic vistas enjoyed by hikers on the nearby Appalachian Trail. In 2015, working alongside a number of conservation partners, we bought the land from the developer for $4.33 million, using money from a variety of sources. The property was then transferred to the National Park Service.

Mosier’s Knob overlookPhoto Credit: TPL Staff, Kathy Haake

Mosier’s Knob overlookPhoto Credit: TPL Staff, Kathy Haake

Broad Dyke Wetlands

There aren’t many pieces of riverfront property on the Delaware that have been in the same hands for more than 300 years. But such a parcel became available in 2011 when Emmanuel Episcopal Church on the Green, located in New Castle, Delaware, decided to sell 60 acres it had owned since 1719.

The church did not want to see the land developed, however, and asked the city for help. The city, in turn, reached out to us, which arranged funding for the $1.2 million purchase from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Delaware Land and Water Conservation Trust Fund.

The City of New Castle now owns and manages the land as a natural area, called Broad Dyke Marsh. The deal ensured the protection of one of the few remaining undeveloped tracts on the Delaware River, one that includes freshwater and saltwater wetlands, forested uplands, and tidal mudflats. It also allowed New Castle to extend its Riverwalk bike and pedestrian path for more than a quarter mile.

Bear Swamp Creek

In a rugged corner of New Jersey’s Pine Barrens, Bear Swamp Creek was recently threatened when longtime property owners in the area wanted to build a subdivision on 413 acres. The parcel, in Southampton Township in Burlington County, was important for a few reasons. Lying in the Delaware River watershed, the land includes the headwaters of Bear Swamp Creek and sits atop an aquifer that supplies drinking water to a million residents. It is also a stopover for migratory birds and home to the endangered Pine Barrens tree frog.

In 2016, we protected the property, which is now part of the Bear Swamp at Red Lion Preserve, owned and managed by the New Jersey Natural Lands Trust. Visitors can see a large wetland forest comprised of pitch pine lowlands and rare Atlantic white cedar swamps that occur in a narrow band only on the East Coast.

Delaware State Forest: Blooming Grove addition

Named for the nearby Delaware River, Pennsylvania’s Delaware State Forest measures over 80,000 acres. Its glacial lakes, bogs and abundant plant and wildlife are spread across four counties. Conservationists in Pike County had long sought to expand the forest by adding 310 acres in the township of Blooming Grove, Pennsylvania.

In 2012, after buying the parcel, we transferred it to the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry, marking our second conservation project in the county. The Blooming Grove addition also extended a seven-mile trail system developed by the Pike County 4-H Club and the Bureau of Forestry.

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.