The hazards of park disparities during heat waves

The hazards of park disparities during heat waves

When a heat wave swallowed much of the Eastern seaboard in late July 2020, it broke temperature records from New Hampshire to Virginia and placed further strain on public health and healthcare systems already stretched thin by the coronavirus.

Even in normal times, heat is dangerous: It’s responsible for more deaths in the United States than any other type of severe weather. But during a pandemic, staying cool in the summer is that much harder: To reduce the risk of virus transmission, places like beaches, public pools, air-conditioned office buildings, and emergency cooling centers either closed or had their capacity limited.

A man and his son enjoying the splash pad feature at Historic Fourth Ward Park in Atlanta, Georgia.Photo Credit: Christopher T. Martin

A man and his son enjoying the splash pad feature at Historic Fourth Ward Park in Atlanta, Georgia.Photo Credit: Christopher T. Martin

Parks are helping people cope. In densely populated areas, the shade of a deep green park can be up to 17 degrees cooler than the surrounding neighborhood. You don’t even have to spend time in the park to reap its cooling benefits: In a 2020 report, data scientist at The Trust for Public Land revealed that neighborhoods with a park nearby are up to 6 degrees cooler than those that don’t have a park within a half-mile.

[Download the full report: “The Heat is On”]

“Greenery and trees bring down the overall temperature of an area, and at night they serve to cool the neighborhood rather than trap the heat,” said Surili Patel, director of the American Public Health Association’s Center for Climate, Health and Equity. “Parks will offer some reprieve for those who don’t have air-conditioning.” The bigger and leafier the park, the more potent its cooling powers.

Park disparities are a health hazard

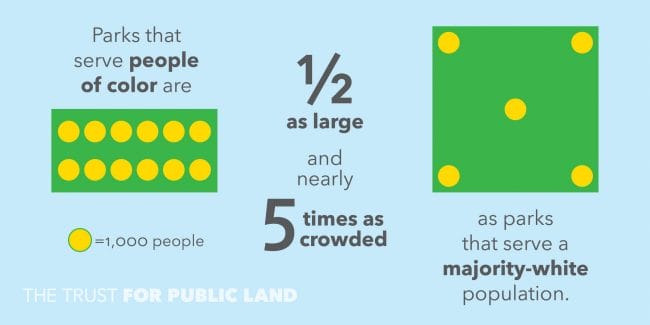

But not everyone has access to the kinds of expansive outdoor spaces that can protect people from summer heat—or allow them to keep a safe social distance from their neighbors. The report also found that across the United States, parks serving primarily nonwhite populations are half the size of parks that serve mostly white populations, and five times more crowded.

Photo credit: The Trust for Public Land

Photo credit: The Trust for Public Land

These findings are troubling—but they come as no surprise to activists like Latino Outdoors founder José González. He’s well-versed in the ways our nation’s history of investment in all kinds of resources has shorted communities of color. “We need to look at how parklands came to be … how they were designed, who they were designed for, and what the historical reasoning was for that,” González says. During a public health crisis that’s disproportionately affecting people of color—Black and Latinx people are three times likelier to contract the coronavirus, and twice as likely to die from it as white people—park inequities both reflect and intensify the effects of structural racism across the country.

[Read more: In a heat wave, parks are literally the coolest]

A recent policy win shows the way forward

We’ve been working alongside communities to close the gaps in park access, size, quality, and investment for almost 50 years. And we’ve long fought for policies designed to fund parks and public lands where they’re needed most. Just this week, we celebrated a huge legislative milestone with the passage of the Great American Outdoors Act. The new law mandates $900 million every year for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, a key federal program for park development and open space protection that’s shaped public spaces in nearly every community in America.

[How well is your city meeting the need for parks? Explore the 2021 ParkScore® rankings.]

This stable, predictable public funding for parks will be an important tool communities can use to invest in healthier, more equitable, more resilient communities for all. “This is an opportunity to continue to see parks as essential, and not just a nicety,’” González told NPR. “In the past, they tended to be one of the first things to get cut. You would see with cities: ‘Protect fire, protect police, parks can wait until the very end.’ We can’t afford to continue to do that.”

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.