How New Orleans nuns joined the fight against climate change

How New Orleans nuns joined the fight against climate change

Since 1855, the Sisters of St. Joseph lived and served in the heart of a New Orleans neighborhood called Gentilly, their congregation based on a 25-acre oasis of pines and maples. But for the nuns, as for so many people throughout the Gulf Coast region, Hurricane Katrina changed everything.

“The convent was under eight feet of water,” says Sister Joan LaPlace. The pews floated away in the flood, along with the organ and the altar. Just getting the water out cost a quarter of a million dollars. Less than a year later, the convent was struck by lightning and burned to the ground.

With developers lining up to purchase the property, the sisters gathered to divine a solution in line with their calling to serve. “Just make it clear, Lord,” says Sister Pat Bergen, recalling their prayers. “Tell us how you want us to use this land to minister to the people of New Orleans.”

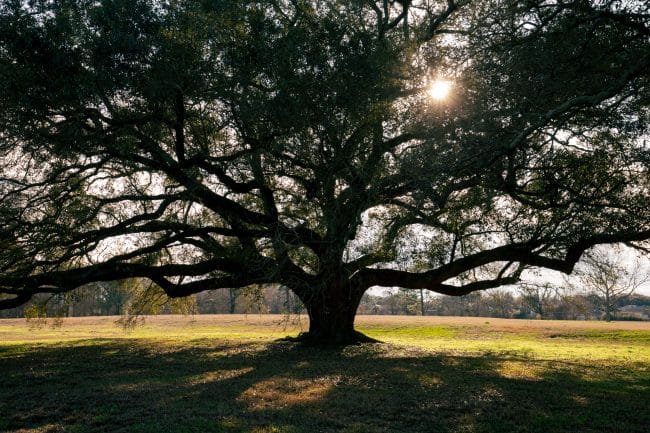

Today, the convent of the Sisters of St. Joseph is a 25-acre open space in Gentilly. Since Katrina, the sisters have sought a way to put their flood-damaged property to use for the good of their community.Photo credit: Bryan Tarnowski

Today, the convent of the Sisters of St. Joseph is a 25-acre open space in Gentilly. Since Katrina, the sisters have sought a way to put their flood-damaged property to use for the good of their community.Photo credit: Bryan Tarnowski

The answer to the sisters’ prayer took the unlikely form of the architect David Waggonner. He told them about the city’s plan to use “green infrastructure” to help control flooding, and how the congregation’s property—one of the largest unpaved spaces in the neighborhood—might fit in. Convinced, the sisters decided to allow the city to transform the land into a public park. Their terms were charitable, to say the least: a 99-year lease for a dollar.

When the new park—dubbed the Mirabeau Water Garden—is complete, it will retain up to 10 million gallons of stormwater, reducing flood impacts throughout Gentilly. “The water is your friend, you can’t just fight it,” Sister LaPlace says. “You can see from the [empty] streets and the terrible conditions of many houses just falling apart—the land sinks when there isn’t enough water. If we can provide this place it would help this neighborhood—our neighborhood.”

With half their land below sea level, New Orleanians today rely on an aging, imperfect network of pumps and canals to keep them dry.Photo credit: Bryan Tarnowski

With half their land below sea level, New Orleanians today rely on an aging, imperfect network of pumps and canals to keep them dry.Photo credit: Bryan Tarnowski

With 64 inches of rain a year on average and half its land below sea level, New Orleans is one America’s wettest cities. Building green infrastructure on the scale needed to keep residents safe from flooding will require hundreds of millions of dollars in public investment—and it has to start somewhere.

In 2016, The Trust for Public Land helped the City of New Orleans secure a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to fund a pilot project in Gentilly. The Gentilly Resilience District will include new, water-absorbing parks—such as the Mirabeau Water Garden—permeable pavement, and incentives for residents to invest in stormwater retention on their own properties, too.

You can learn more about how New Orleans residents are coming together to forge a more resilient future—and how The Trust for Public Land is pitching in with big data and green infrastructure expertise—in “Taking On Water,” a story by Julia Kumari Drapkin in the latest issue of Land&People magazine.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to pass the Outdoors for All Act to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.