A landmark case comes to life on the new Civil Rights Trail

A landmark case comes to life on the new Civil Rights Trail

When she was in the third grade back in 1950, Linda Brown Thompson rode the school bus to Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Linda is black, and although her neighborhood at the time was integrated, the city’s elementary schools were not. It rankled Linda and her parents, Oliver and Leola, that she had to ride the bus rather than walk a few blocks to a much closer school with her friends.

Linda Brown at Monroe School in 1954.Photo credit: Washington Post Magazine via University of Virginia

Linda Brown at Monroe School in 1954.Photo credit: Washington Post Magazine via University of Virginia

Linda’s father, Oliver Brown, became the first named plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit by 13 parents who sued the Topeka Board of Education to reverse its segregationist policy. The case—along with similar suits from four of the other 21 states with segregated schools—eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1954, the court issued a unanimous decision in Brown v. the Board of Education: “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

At age ten, Katherine Sawyer testified before a Topeka court in the early stages of the case that would become Brown v Board of Education.

Katherine Sawyer Interview Topeka, KS from Civil Rights Trail on Vimeo.

Brown v. Board was a major blow to institutionalized segregation in the United States and is considered one of the earliest legal victories of the civil rights era. The precedent set by this landmark case changed the world. But by the early 1990s, the landmark itself—the solid hull of Linda Brown’s Monroe Elementary School, once a stately brick building—was vacant and crumbling, in danger of being torn down. We rallied with community members to save the building and transferred it to the National Park Service, which today welcomes visitors to the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site.

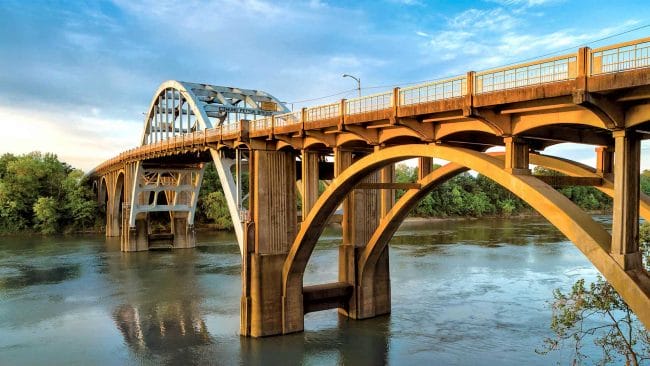

Monroe School is one of a hundred sites across 15 states included in a new effort to tell the story of the civil rights movement on the ground, from the very schools, businesses, homes, churches, and streets where it happened. Designated on January 1, 2018, the United States Civil Rights Trail includes famous places—like the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, and the Woolworth’s department store in Greensboro, North Carolina, that launched the student sit-in movement—as well as lesser-known sites like the West Virginia home of NAACP board member Memphis Tennessee Garrison.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, was the site of a violent confrontation between civil rights marchers and law enforcement in 1965.Photo credit: Civil Rights Trail

The Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, was the site of a violent confrontation between civil rights marchers and law enforcement in 1965.Photo credit: Civil Rights Trail

We’ve long helped communities preserve the places that tell the story of the civil rights era. Several of these sites—like Monroe School in Topeka, John Brown’s Fort at Harper’s Ferry National Historical Park, and the Atlanta neighborhood where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. grew up—are included in the new Civil Rights Trail. Others, like Boston’s African Meeting House and Florida’s American Beach, continue to welcome locals and visitors to explore the history of the movement elsewhere.

“It’s great to see coordination between civil rights landmarks that will allow people to visit and explore sites that have shaped our country,” says Jay Wozniak with Trust for Public Land’s Atlanta office. Wozniak is part of the team that’s building the 16-acre Cook Park in Atlanta’s Vine City neighborhood, a center of activism during the civil rights era. “We’ve helped communities save places like these so that future generations can learn from our past—and it’s rewarding to see that happen.”

The seed for the trail was planted more than two years ago, when the director of the National Park Service challenged historians to create a thorough inventory of landmarks associated with the civil rights movement. Researchers from Georgia State University joined forces with tourism departments from several southern states to create a list of places that bring the greatest triumphs and tragedies of the era to life.

The sites are listed and described on a new website that also offers sample itineraries for visitors hoping to explore different themes of the civil rights movement, such as the pivotal campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, or the bravery of the Freedom Riders. Monroe School in Topeka is a stop on a trip through eight sites that played a role in school integration.

Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, is a stop along the Civil Rights Trail that carries the story of the movement’s fight to desegregate public schools.Photo credit: Civil Rights Trail

Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, is a stop along the Civil Rights Trail that carries the story of the movement’s fight to desegregate public schools.Photo credit: Civil Rights Trail

The National Park Service oversees several groupings of historic sites, including the Trails of Tears National Historic Trail, which traces the routes of Native Americans forcibly expelled from their homes in the Southeast to present-day Oklahoma in the 1820s and 30s. But until last month, there was no such system for the sites that contributed to the civil rights movement.

“Hopefully when people hear about the civil rights trail, it will make them aware there are locations near where they are that changed the world,” said Lee Sentell, Alabama’s state tourism director, in an interview with the New York Times. “I’m just surprised this hadn’t been done earlier.”

That the Civil Rights Trail is new may be surprising, but the tourism industry’s role in helping make it easier to visit the movement’s landmarks is not. The industry is responding to many Americans’ growing interest in learning about and paying respects to civil rights heroes—and see for themselves the places where history was made.

At the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, visitors can stroll the same streets as the civil rights icon. Trust for Public Land has helped conserve and restore the district’s historic homes.Photo credit: Christopher T. Martin

At the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, visitors can stroll the same streets as the civil rights icon. Trust for Public Land has helped conserve and restore the district’s historic homes.Photo credit: Christopher T. Martin

For her part, Linda Brown Thompson was in junior high by the time the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board. She eventually attended Washburn and Kansas State universities and has continued to speak up for equality and civil rights—and share her family’s story—throughout her life.

Remembering the day of the Brown decision, Thompson has said, “I learned about it when I got home from school, and I knew that my sisters would not have to go to a segregated school. That evening in our house there was much rejoicing—I remember tears of joy from my father, who kept repeating, ‘Thanks be unto God! Thanks be unto God!’”

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to pass the Outdoors for All Act to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.