River-trip reflections on conservation battles past and present

River-trip reflections on conservation battles past and present

The steady current of the Green River pulls our rafts and kayaks toward what looks like a geologic impossibility.

Ahead of us is a gigantic gap, a thousand feet deep, where the river appears to flow placidly right through the Uinta Mountains of northeastern Utah. As we enter, we crane our necks to look up at the cracked cliffs on either side. A great blue heron stalks fish by the riverbank. Box elder, juniper, and a few cottonwoods grow on broad sandbars. We notice movement on our left and glance over to see two bighorn sheep sprinting up a steep scree slope with mind-boggling speed and agility.

These are the Gates of Lodore, inside the Dinosaur National Monument. My group of friends and family—along with a handful of river guides—are here to experience one of the West’s most celebrated wilderness whitewater river trips. The first afternoon finds our boats gliding into the roaring throat of a Class III rapid, squeezing between two boulders and skirting an intimidating “hole” where recirculating water can flip a fully loaded raft.

I watch my 15-year-old son, Nate, his expression serious and focused, as he paddles his kayak flawlessly through the trip’s first big rapid. Nearby in one of the rafts, my 13-year-old daughter, Alex, screams with excitement and delight.

Nate, 15, is unphased by the name “Upper Disaster Falls.”Photo credit: Michael Lanza/TheBigOutside.com

Nate, 15, is unphased by the name “Upper Disaster Falls.”Photo credit: Michael Lanza/TheBigOutside.com

On our third day on the river, we float through Echo Park. Here the Yampa River joins the Green between sheer walls of gleaming, golden Weber sandstone. As is the custom for boaters, we shout at the soaring cliffs and listen to our voices bouncing back at us seconds later.

Echo Park would have been submerged under a reservoir hundreds of feet deep if not for a conservation battle now recognized as one of the great victories of the environmental movement. In the 1950s, the proposed Colorado River Storage Project would have erected two dams inside Dinosaur National Monument: one a few miles downstream from Echo Park, and a second dam at Split Mountain, where our trip ends.

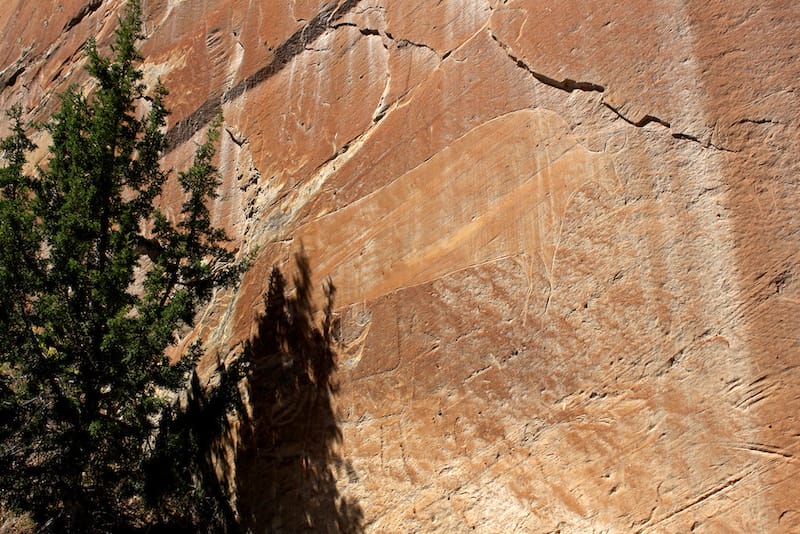

The dams would have completely inundated these magnificent canyons—submerging the rapids, this rich habitat for bighorn sheep and other wildlife, and scores of pictographs painted by the people who lived here a thousand years ago. But a coalition of conservation groups fought the proposal, rallying public opposition. In the end, they persuaded Congress to remove the dams in Dinosaur from the project.

The proposed dams would have flooded the canyons, submerging wildlife habitat and ancient art. Photo credit: Dinosaur National Monument

The proposed dams would have flooded the canyons, submerging wildlife habitat and ancient art. Photo credit: Dinosaur National Monument

Today, these canyons testify to the wisdom of protecting special places in perpetuity—rather than exploiting them for short-term economic gain. So as I stare up at the imposing walls, I feel a welling anger and disappointment to think that they may come under threat again.

We are in the midst of a new political battle over our public lands. At stake is our access to resources that belong to all of us, as citizens. These are the places we use for rafting and kayaking; for hiking, backpacking, and camping, for climbing, hunting, fishing, horseback riding, and more. These are the places that support an outdoor industry that generates $646 billion in consumer spending—more than U.S. auto sales.

In Idaho, where I live, a small but persistent group of politicians contend that the state can manage these federal lands better than the U.S. government does now. In reality, the state budget could not accommodate even the cost of managing a major wildfire in a national forest. The end result of a state takeover of federal lands, therefore, would likely be the sale of those lands to private interests—free to cut off public access and exploit the land to maximize profit.

New legislation threatens public access to land that’s long belonged to all of us.Photo credit: Michael Lanza/TheBigOutside.com

New legislation threatens public access to land that’s long belonged to all of us.Photo credit: Michael Lanza/TheBigOutside.com

In an 1897 article in the Atlantic Monthly, John Muir wrote: “Any fool can destroy trees. They cannot run away, and if they could, they would still be destroyed—chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides.” That sentiment—the recognition of the vulnerability of the land—informed the founding of the U.S. Forest Service a few years later.

If not for such efforts decades ago, my family and our friends would not be floating down this remarkable canyon today. On our last afternoon in Dinosaur National Monument, as we bounce down smaller rapids with our journey’s end in sight, I think about the battles of the past and the ones at hand. I hope we, too, will have the foresight to see through the false promises of those who would sell off our national heritage—that we, too, will choose to protect places like this.

Trust For Public Land media partner Michael Lanza blogs about his outdoor adventures, including many with his family, at The Big Outside. His award-winning book Before They’re Gone—A Family’s Year-Long Quest to Explore America’s Most Endangered National Parks, chronicles his family’s wilderness adventures in national parks threatened by climate change.

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.