When Trust for Public Land opened its doors with one employee, in San Francisco, in the early 1970s, Jimmy Carter was on the other side of the country becoming a charter member of the Georgia Conservancy, an organization that also focused on conservation, economics, stewardship, and sustainability.

President Carter’s love for the land, and his commitment to serving and protecting it, was rooted in his faith. His grandson Jason Carter reflects, “Both his faith and his life on this earth have been about connecting him to the earth in a fundamental way…In my family, we’ve always looked at the land as something that brings people together, as the most sacred obligation that we have.”

In his life, President Carter has fulfilled this calling in many different ways: as a farmer, who knew intimately the connection between the health of our land and the sustainability of our lives; as a naval officer on the open seas; as a governor and a president who protected more natural spaces and created more parks than the six previous presidents combined.

There are hundreds of stories to be told about President Carter’s legacy of service to the land.

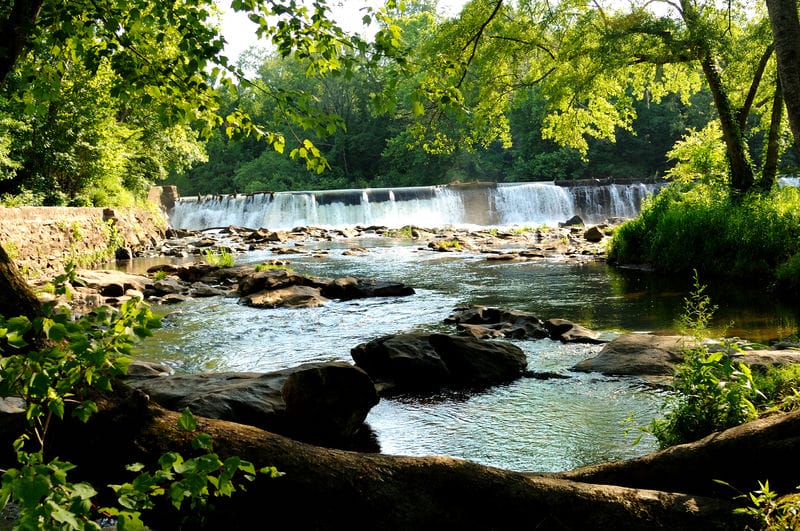

This story is about a river.

In the Beginning, There Was a River

The Chattahoochee River begins in the Blue Ridge Mountains and flows southwest along the Georgia/Alabama border and into Florida. Humans have lived alongside the river since at least 1000 BC, building cultures and economies on its banks.

Rivers have always brought people together. Indigenous tribes grew so close while living on the banks of the same river that they developed a united tribal name: The Creeks, of Chattahoochee.

To this day, anyone who lives in the Southeast in some way relies on the Chattahoochee River for their wellbeing. It is the primary water source for the region surrounding Atlanta; the smallest water source for any industrial area in the country, according to the Georgia River Network. Its water also serves to power the farms and industries that drive the economy. President Carter recognized the critical importance of this river to the region when he signed a law in 1978 establishing the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, a 48-mile segment of the Chattahoochee River, through the heart of Atlanta, Georgia.

But the river has always been vulnerable, flowing through the industrial heart of the new South. Aggressive growth in the 1980s put the river at risk with so much of its land still unprotected, pollution rising, the ecosystem under siege. In 1991, American Rivers named the Chattahoochee the most endangered river in America. President Carter had started the work, but it would take more than one person to save the river.

“Trust For Public Land helped us understand the possibility, years ago, of protecting the Chattahoochee right through the middle of Atlanta, and Newt Gingrich went and got the money,” remembers P. Russell Hardin, President of the Woodruff Foundation, a leading advocate and ally in the quest. Says Hardin, “You know, conservative and conservation have the same root.”

House Speaker Gingrich may have worked on the other side of the aisle from Carter, but he fished from the same river banks, and he shared the same deep love of land.

Gingrich issued a challenge to Atlanta’s conservation community: if you can raise $25 million, I’ll get the government to match it.

In fact, the river’s advocates, working across lines of business and conservation, across party politics, from private sector to public, far exceeded their initial goal. In total, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, the team raised $50 million in private funds, and $175 million in public funds. With these resources, they preserved 18,000 acres and 80 miles of riverfront.

“It was an audacious concept that has been wildly successful,” Hardin remembers, with pride.

Thanks to the intervention of Woodruff and Speaker Gingrich and scores of advocates and allies, we saved the river. The river is healing.

But what about us?

We Save Rivers, Then Rivers Save Us

Jackie Cushman grew up playing on the banks of the Chattahoochee with her father, an environmental studies professor better known as eventual Speaker of the House Gingrich. From her father, she knew the power of nature, and water in particular, to heal people and communities. Ms. Cushman and other advocates and partners purchased and protected the 18,000 acres along the Chattahoochee. But they also saw a community fractured and increasingly separated from it. They saw children who live just a mile from the Chattahoochee who have never put their feet in the water.

“On things like conservation, we actually had a genuine bipartisanship that was very effective. The Chattahoochee repays us for our effort of conservation every single day,” says Gingrich.

Speaker Gingrich taps into something elemental here. The point is not only that we can save the river. The truth is that the river may be able to save us. That is the mission we are working towards today. Help us realize the promise of the Chattahoochee RiverLands.

“We had preserved all this land, but not enough people were using it,” she remembers. “We wanted to change that dynamic.” Trust for Public Land partnered with the City of Atlanta and local metro planning organizations, and created a vision for a hundred-mile greenway through the heart of metro Atlanta. This coalition of more than 80 organizations launched an effort known as the Chattahoochee RiverLands, and together they are imagining a transformation of this ancient river, and all the people who live alongside it.

“I think the most important thing is that we are providing access to the greatest natural internal resource in Georgia to millions of people, says Jackie Cushman, TPL Georgia advisory board member. “I think we all understand after COVID that human beings need to be in nature. We need to be outside. And not only do we need to be outside, we need to be outside with people… You want the shared experience of being somewhere safe together outside in God’s creation.”

The historian Rebecca Solnit notes that our ability to create a better future begins with our imagination. And the ability to create a better world, as President Carter always knew, begins with the ability to imagine a better world. “It’s really important for humans to get to natural spaces, and if everyone does it, a generation from now, we’ll be a better country,” says Speaker Gingrich. This is the core of the RiverLands project. It is an audacious work of imagination.

Its champions imagine a hundred-mile continuous greenway and blueway that will reunite the river with the community around it. They imagine an ecological refuge, a trail network that will connect 40 different parks. They imagine breweries and restaurants. They imagine children who have never felt their feet in a current, standing in the river, and understanding the world in a different way.

It’s an ambitious project: the most ambitious in TPL’s history.

George Dusenbury, TPL’s Georgia state director, has found deep success in connecting with people from every stage of life and every point on the political spectrum, to create the Chattahoochee RiverLands Trust. “This is something that transcends politics,” he says. “Parks are something that you can see and feel; they’re tangible. There’s a permanence to that. You’re protecting and creating this special place. I think every political value aligns with this.”

Jason Carter’s family may be associated with one political party, but he likes to think about all the ways that land, and rivers, can connect people across all kinds of boundaries. “As we talk about equity—what equity really means, I think—is that…there’s groups of people that have become disconnected from the type of opportunities that other people have. And that goes in both directions. When you talk about healing people, when you talk about bringing people together, those things are about finding the best ways to connect.”

Centuries since tribes first built communities along its banks, 60 years since President Carter took the first step to preserve this sacred waterway, the Chattahoochee is showing us that rivers have the power to unite us still. Two of the people who are helping to lead the work of the RiverLands are Jason Carter and Jackie Cushman. The grandson of President Carter and the daughter of Newt Gingrich, but more than that, two people who, regardless of their family’s political differences, grew up understanding our shared alliance.

“All of us have lives now in 2023 that get covered up with all kinds of things that divide us from our fundamental nature. And being able to get back to that, and to reconnect with that, is sort of a very important way to build back those reservoirs of patience and love and commitment,” says Jason Carter.“When you build those spaces and let people get back to them, it’s a sort of a reawakening of who we are at our core.”

Jackie Cushman knows how much work awaits to realize this vision. But she also knows how much work has already been done. And she knows that the river is ready. “If you’ve seen the right of way where they’re doing the work, it looks like it’s just sitting there waiting for trails. It’s so incredibly beautiful, and it has this huge canopy of trees and this cleared green pathway. It’s just sitting there waiting for people to come. It’s so beautiful.”

Jimmy Carter has left us with so many legacies, and history will record them all, but perhaps none will be greater than this river, this living symbol of what can happen when we come together across generations and across politics. When we are resilient and determined and imaginative because no matter what divides us, we recognize the power of rivers, the power of nature, to unite and connect us. Just as President Carter always imagined, just as he set out to do, more than 60 years ago.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.