“What has been missing in environmental policy is the link between environmental restoration and economic growth, both in our own country and around the world. There will be no peace without ecological restoration, and with restoration, over time will come the economic growth to eliminate poverty and build societies that value human rights.” – Statement from Huey Johnson upon receiving the Sasakawa Environment Prize from the United Nations Environment Programme in 2001.

In the early 1970s, Huey Johnson learned about an effort to protect the Marin Headlands—the iconic rolling green hills that flank the north end of the Golden Gate Bridge. To the dismay of the local community, including hikers and environmentalists who treasured the landscape, the Headlands had been slated for a massive housing complex—including high-rise apartment towers and hundreds of houses and townhomes, a mall, and an upscale hotel.

Huey Johnson, a key player in the protection of the Marin Headlands, later recruited lawyers and conservationists to start Trust for Public Land, which would go on to protect more than 5,000 places, including nearly a dozen within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Photo: Robert Campbell

Huey Johnson, a key player in the protection of the Marin Headlands, later recruited lawyers and conservationists to start Trust for Public Land, which would go on to protect more than 5,000 places, including nearly a dozen within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Photo: Robert Campbell

Local attorneys had mounted a lawsuit in opposition to the development, eventually proving it was improperly zoned. At the same time, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) was just taking shape. Recognizing an opportunity, Huey Johnson convinced The Nature Conservancy, where he served as western regional director and later as president, to option the property for acquisition by the National Park Service and incorporation into the GGNRA.

The protection of the Marin Headlands property occurred prior to Trust for Public Land’s inception, but the project came to loom large in the organization’s consciousness as a precursor to its founding. Protecting close-to-home parks such as GGNRA would become a signal part of TPL’s mission, one founded on the belief that all people need access to nature and the outdoors in the cities and communities where they live as a matter of health, equity, and justice.

Joining together with a diverse coalition of recruits, Huey Johnson created TPL. We completed our first land protection project—at Bee Canyon in Los Angeles—in 1973, and Johnson served as president until 1977.

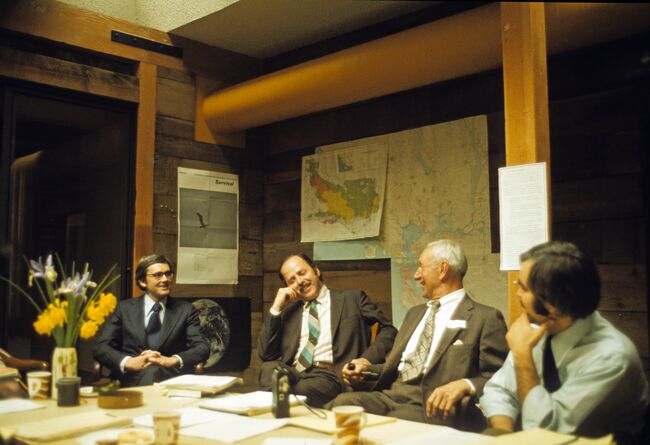

Huey Johnson, second from left, in an early Trust for Public Land staff meeting. Photo: Trust for Public Land archive

Huey Johnson, second from left, in an early Trust for Public Land staff meeting. Photo: Trust for Public Land archive

While many conservation organizations focused on setting aside land for biodiversity or habitat restoration, Huey Johnson and TPL’s founding staff sought to bring the benefits of parks and nature to the places, people, and communities that needed them most.

“He was a swing-for-the-bleachers kind of thinker,” said Felicia Marcus, who served as COO for TPL from 2001 to 2008. “Huey Johnson operated on the idea that you only have one life, so live it, and make the biggest difference you can, take risks, and, if they pay off, you’ve changed the world. He came up with a revolutionary idea that saving land wasn’t the objective—the land was the vehicle by which this magic happens between place and people. And what he created has been a gift to thousands of communities all around the country—an enormous legacy.”

This spirit of innovation would drive Johnson throughout the remainder of his long and storied career following his time with TPL, first as California’s natural resources secretary from 1978 to 1982, under then-Governor Jerry Brown, and later as founder of the Resource Renewal Institute, an organization dedicated to strengthening society’s ability to secure the future health of the planet by fostering innovative solutions to increasingly complex environmental problems.

One accomplishment exemplifying Johnson’s ingenuity happened in the early days of TPL, when he took a phone call from Nicholas Charney, founder of Psychology Today magazine and owner of 1,300 acres of ranchland overlooking Bolinas Lagoon and the Pacific Ocean. The property—40 miles north of San Francisco—was ideally suited to add to the new Golden Gate Recreation Area—but there was no guarantee that Johnson could make that goal happen. On the other hand, if the National Park Service had waited for the wheels of government to turn, the site would be lost. Johnson decided the risk was worth taking and agreed for TPL to option the land, drafting the agreement on a paper napkin over lunch with Charney.

Huey Johnson’s protection of Wilkins Ranch, one of three projects Trust for Public Land completed in its first year of existence, typified the advantages the newly formed nonprofit could bring to conservation—including speed and the assumption of risk. Photo: Robert Campbell

Huey Johnson’s protection of Wilkins Ranch, one of three projects Trust for Public Land completed in its first year of existence, typified the advantages the newly formed nonprofit could bring to conservation—including speed and the assumption of risk. Photo: Robert Campbell

This humble transaction helped generate momentum for an important new type of federal public land. Historically, national parks had been located in remote areas, not within an hour’s drive of millions of people. The GGNRA would be followed by big but accessible federal parks such as the Columbia River Gorge National Recreation Area near Portland, Oregon; the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area on the edge of Atlanta, Georgia; and the Cuyahoga Valley National Park, south of Cleveland, Ohio.

In pursuit of our mission to connect everyone to the joys and benefits of the outdoors, Trust for Public Land would help build all of these federal open spaces over the next 50 years, including nearly a dozen additions to the GGNRA, which is now among the largest and most iconic urban parks in the world.

Johnson died in 2020 at the age of 87. “All of us at Trust for Public Land are deeply indebted to and inspired by Huey and the legacy he created, which lives on in the conversations that families have at the local park, in the smiling faces of children running down the neighborhood trail, and in the breathtaking awe that people feel when they connect to the natural world,” shared TPL President and CEO Diane Regas.

Feeling Inspired?

Donate today to continue our legacy and support 50 more years of connecting everyone to the outdoors.

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to pass the Outdoors for All Act to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.