Casting Flies

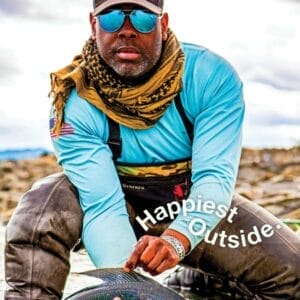

“There’s this thing among anglers—it’s kind of like the fish becomes the by-product. Going fishing becomes spiritual. You’re searching for fish, but you’re also searching for happiness.”

The river accepts everybody.

That’s what Chad Brown likes to tell his teenage students as they follow him into the water. In those moments, these are words of encouragement to first-timers—a talisman against the foreign feel of the fly fishing rods and the unfamiliar pull of invisible currents. But for Brown himself, it’s a belief that saved his life.

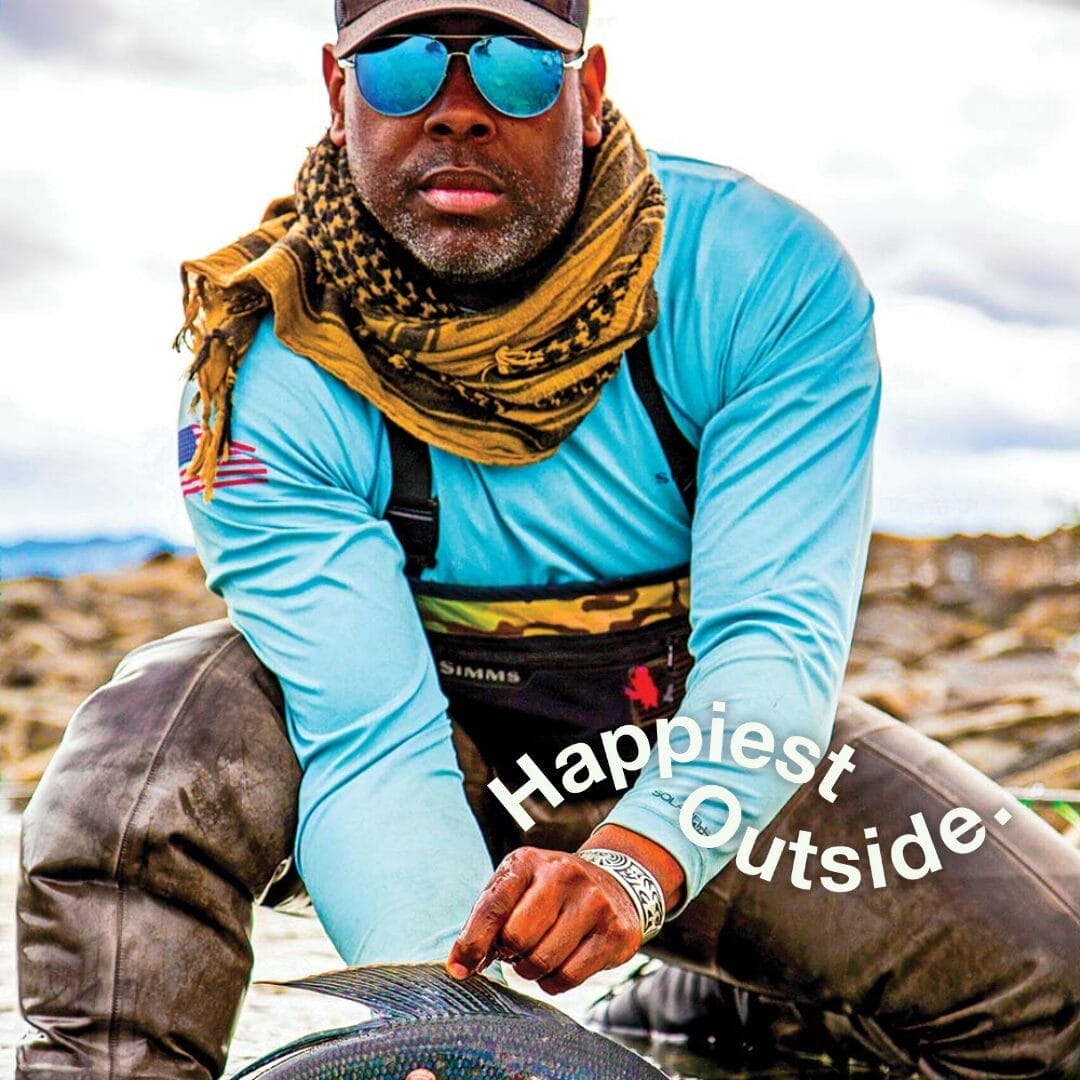

Brown is a U.S. Navy veteran who in the 1990s served in the Middle East, Guantanamo Bay, and Somalia. Years after he returned home to the states, the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder caught up with him. He struggled with alcohol and homelessness. He contemplated suicide. But at his lowest point, Brown discovered fly fishing and the rivers of the Pacific Northwest.

“Whatever medication I was on at the time,” he says, “I remember wading into the middle of that beauty and feeling really alive for the first time in I don’t know how long.”

Brown chased that feeling, returning to the rivers until his head started to clear. A few years after he first picked up a fly rod, he launched what would become a successful business, designing fly-fishing gear that reflects his urban roots and military experience. He named the venture Soul River Runs Deep—an homage to all he’s discovered on the water.

And he didn’t stop there. With profits from the business, Brown started a program that brings fellow military veterans together with students from predominately African American and Latino neighborhoods in his home city of Portland. Together, they study the art, science, philosophy, and discipline of fly fishing.

Though busy preparing for a summer packed full of these “deployments”—river trips from Portland to Michigan and all the way up to Alaska—Brown took some time out to talk about what he found when he went looking for fish.

Was nature a part of your childhood?

I’m from Texas, and I grew up in the city. But on weekends my family would head out to see the grandparents, who had some property outside of town. My dad’s side is hunters, so I spent a lot of time outdoors with my dad and my grandfather and learned a lot about nature and wildlife from them. Age eight, nine, ten, I thought I was a little Daniel Boone or Teddy Roosevelt, mounting expeditions by myself in the woods behind my grandparents’ house, setting traps that never caught anything. I was a tough, wild little kid. I didn’t realize it at the time, but now I recognize that mine was not a typical childhood for a young African American boy in that era.

After you retired from the Navy, you earned your degree, worked for a time in New York advertising, and then moved to Portland. But that was a tough time for you.

Yes. Moving to Portland—the slower pace and the distance from my family—it dislodged some of the darkness that I’d been carrying around with me from my time in the navy. I started drinking; I lost my job and then my housing. I was on and off heavy medications.

I started going fishing in part because I didn’t have a lot else to do. I’d done some rod and reel fishing with my dad when I was younger—where we’d dig up a can of worms and go fish for perch—but I learned to cast a fly from watching YouTube and reading books. I spent hours and days hanging around in fly shops. They became like my living room: good conversation, people coming around to talk about this fly and that river. People there didn’t necessarily know my story, but they accepted me for who I was, and they were down to share what they knew. My friends on the river became like my family.

How did you get back on your feet?

One thing I did learn from my military service was to never give up the fight. Life has dealt me an interesting deck of cards, not all of them good. I can say that life has stripped me down to the skin, to the point where all I’ve had left was that ability to punch through to the other side of the pain. And I tend to fall back on that discipline the military has given me to persevere.

Things changed for me when I launched my business, which melds my two passions: design and fly fishing. Now I’m able to direct a lot of the profits from that toward supporting our program that brings together kids from inner-city Portland with volunteer leaders who are military veterans.

What is it about fly fishing that makes it a good introduction to the natural world?

What is it about fly fishing that makes it a good introduction to the natural world?

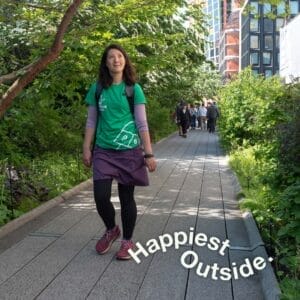

Fly-fishing is something that kids from Portland’s predominately black and Hispanic neighborhoods have not typically been exposed to. It’s a totally new environment, which helps set the stage for learning about themselves and their relationship to the natural world.

To be a keyed-in angler, you need to approach it from a scientific perspective—but also as an art and as a devotion. If you care about catching a fish, then you better care about that fish having clean water to swim in. So we start by talking about ecology and conservation and climate change. Fly fishing is a thread that weaves so many of these important aspects of our lives together out on the river.

What do you hope the students take away from their time on the river with you and the other veterans?

What do you hope the students take away from their time on the river with you and the other veterans?

There is a certain bond that develops when kids and veterans are out in nature together, but that weekend deployment on the river is just the start. We’re forming a tribe of people that stick around for each other. As a veteran, that means going above and beyond the call of duty to stay involved in that kid’s life, their family’s lives. Our vets are showing up to the kids’ school assemblies, football games—even a court date.

And for their part, when kids come home from the program, they’re talking about their conversations with the veterans and what they’ve experienced in nature, and they’re bringing that like a bottle of medicine and dumping it right into the nucleus of the living room. They are becoming advocates for the environment and bringing their families along with them.

All that from a fishing trip?

All that from a fishing trip?

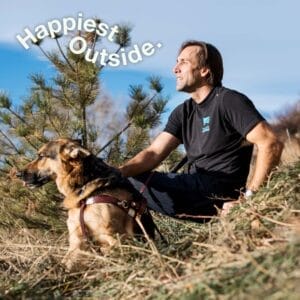

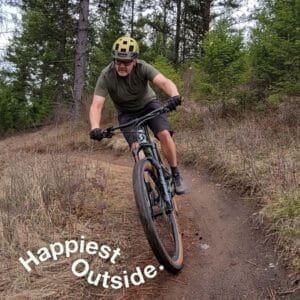

I’m not really out there pushing fly fishing. My soul river is fly fishing, but your soul river could be backpacking, or it could be mountain biking, or writing a poem, or getting real into birds. What I want to highlight for people is that there’s a place in the outdoors where you can find your healing. It’s about knowing where to go so you can find the strength to deal with whatever life might send your way.

I think that’s why I like fishing for steelhead. It’s not for the faint of heart. You’ve got to be a little nuts to go out there in the dead of winter, submerge yourself waist deep in freezing water so that half your body goes numb while sleet and ice blow in your face. You’re standing there for eight hours trying to hook into that one fish, and chances are you won’t catch it. Guys go three, four years of not even hooking one. It took me five years before I hooked a steelhead. But you remain consistent in your approach, getting back to that river every opportunity you can get, regardless of the weather. It’s kind of like the wild is calling you and you’ve got to be constantly answering that phone.

This Q&A is excerpted from the original version that ran in the 2017 spring/summer issue of Land&People magazine. All photos courtesy of Chad Brown.

What do you hope the students take away from their time on the river with you and the other veterans?

What do you hope the students take away from their time on the river with you and the other veterans? All that from a fishing trip?

All that from a fishing trip?