Schoolyards: The park access solution that’s hiding in plain sight

America has a park problem. Nature is essential for healthy, happy communities, but today, 100 million people in this country—a third of us!—don’t have a park within a 10-minute walk of home.

The Trust for Public Land is focused on fixing this problem. That’s why we created the world’s most comprehensive geospatial database for park access—and we’re putting it to work to pinpoint where parks are needed most, and where and how to invest for a future in which everyone has nature nearby.

To close our country’s gaps in park access will definitely require the creation of some new parks. But it will also require us to get the most use from the open space we already have, in places like forgotten alleyways, postindustrial waterfronts, and asphalt-covered schoolyards.

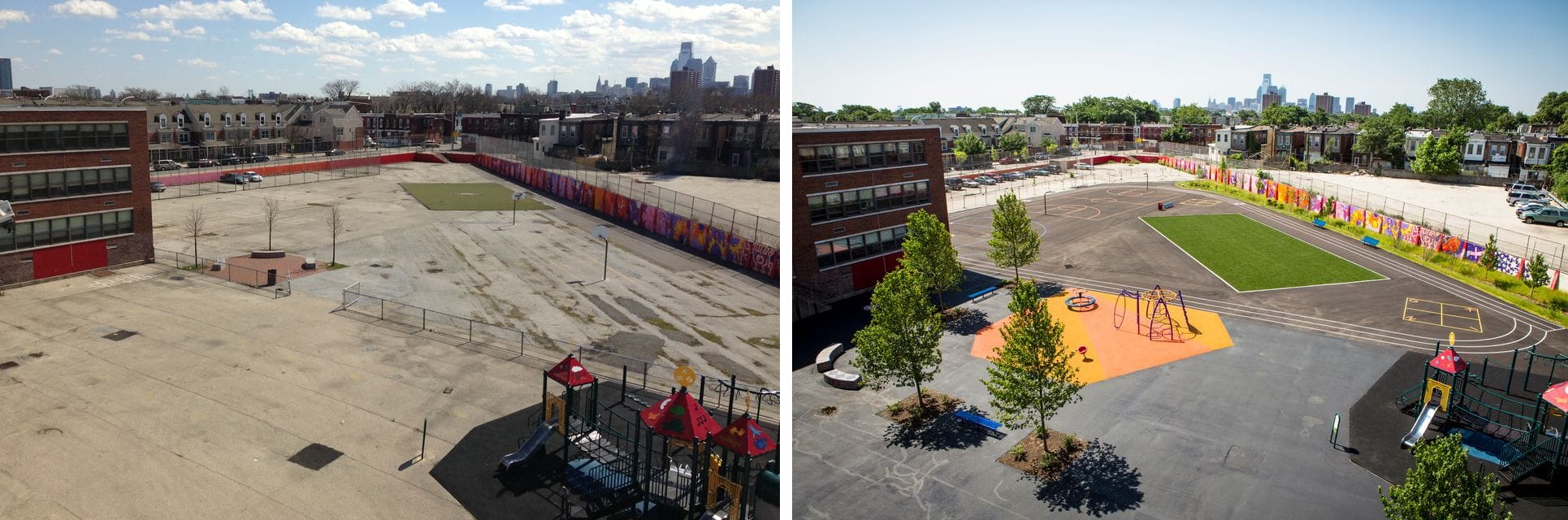

Today, America’s schoolyards are packed with potential. Collectively, public school districts own tens of thousands of acres across the country. In a few places, schoolyards are vibrant community hubs, open to the public after school hours and designed to meet the needs of neighbors as well as students. But in too many communities, schoolyards look more like parking lots than playgrounds, and their gates lock as soon as students head home for the day.

The Trust for Public Land has been helping communities make the most of their schoolyards for nearly 50 years. Every school in every neighborhood in every city is different, but over time, we’ve developed a few guiding philosophies:

1. Schoolyards should be designed for the community, by the community

For the most part, schoolyards have been designed—IF they’ve been designed—to meet the needs of students alone. But there’s a better way: we help communities transform their schoolyards using a participatory design process that invites the whole community—from students and teachers to neighbors and other local groups—to weigh in on what the space can be. The result? A place brimming with one-of-a-kind artwork, custom play areas, plenty of space to run around, and useful features for neighbors of every age. When neighborhoods unite to design their schoolyards, they create places that reflect what’s important to the whole community, where everyone feels welcome.

Over a three-month participatory design process, we rounded up ideas from students, neighbors, and staff at a nearby community center to imagine a brighter future for the schoolyard at P.S. 7 in the Bronx—one of the more than 200 playgrounds we’ve created in New York City. The result is a custom play area, plenty of shady benches and tables for families and seniors to hang out, and a running track where anyone in the neighborhood can work out when school isn’t in session.

2. Schoolyards should be shared

If a community comes together to imagine a great schoolyard, they should be able to use it! But it’s not as simple as leaving the gates unlocked: public access can mean more maintenance costs, and raises questions around liability—and public school districts shouldn’t be expected to take on the added burden alone. That’s why The Trust for Public Land helps communities implement “shared-use agreements,” contracts between a school district and other local agencies that can resolve liability concerns and shift the burden for increased costs and maintenance away from school districts.

In Houston, the SPARK School Program works with schools and neighborhoods to develop community parks on public school grounds. In the past 30 years, SPARK has built over 200 parks throughout the Houston metro area, improving access to the outdoors for nearly half a million people.

3. Schoolyards should be green

Opening schoolyards to the public can help fill in some big gaps in the map of park access in America. But access alone isn’t enough. In many cities, the typical schoolyard is a fenced-in expanse of blank asphalt—a featureless space more akin to a prison yard or parking lot than a park. That’s why we help communities imagine, fund, and build schoolyards packed with trees, grass, gardens, and other climate-smart features that capture stormwater. Green schoolyards reduce the risk of flooding, and combat the urban heat island effect, keeping our cities cooler. They’re places where birds and pollinators find refuge, and double as outdoor classrooms where kids can learn about the natural world every day, all year long. And since every green schoolyard we build is open to the public when school isn’t in session, green schoolyards serve as neighborhood parks, where anyone is welcome to pause, breathe, and experience nature’s benefits, even in the heart of the city.

“Right now the typical schoolyard in Philly is just asphalt, and it’s usually in bad shape,” says Helaine Barr, a policy analyst with the Philadelphia Water Department. “But they’re often the only open spaces in dense neighborhoods, so they offer a great opportunity to capture stormwater.” At William Dick School in north Philadelphia, we helped students design a cooler, greener—and way more fun—schoolyard.

Of the 100 million people in this country today who do not have a park within a 10-minute walk of home, almost 20 million of them do live that close to a public school. That means if every public schoolyard were designed for the broader community, with greener features, and open to the public, we’d already be a fifth of the way to solving the problem of outdoor access for everyone in America.

Want to learn more about how we’re using data to help connect more people to nature? Check out tpl.org/parkscore.