But even as Chattanooga’s transformation is held up as a model, stark disparities persist in measures of mobility, education, and health. White households in Chattanooga earn twice as much as black households. Black residents are 30 percent more likely to die from strokes or heart disease. For working-class residents and minorities, wages have remained stagnant and housing prices have ballooned.

They reached a bend in the river called Blue Goose Hollow, where they sat on rocks and took in the view.

To the south, Lookout Mountain ascended above the trees. Across the river, barges lay moored against the shore. Behind them, rows of new condos lined the path that led northeast to the city’s center. Two large, colorful sculptures anchored the trailhead, and the kids posed for a photo among the steel whorls of green, purple, red, yellow, and blue.

“They kept saying, ‘It’s so pretty,’” recalls Raquetta Dotley, who led the field trip. “I just watched them take pictures and I kept thinking: ‘This is just a couple of miles from your house, but you had no idea it was here.’”

The children live in Alton Park, a neighborhood less than a mile from the Riverwalk, but the busy roads that surround the neighborhood make it difficult and dangerous to walk to downtown. “These kids live so close to this trail, but they are still so disconnected from it,” says Dotley, who directs an Alton Park–based community organization called Net Resource Foundation.

Today Chattanooga is at a crossroads. For thirty years, the city—with help from The Trust for Public Land—has steadily grown its trail system, transforming the bones of its industrial past into a thriving greenway network that has sparked a remarkable urban renaissance. But many Chattanoogans—especially those living in low-income communities of color—can’t access these trails and still don’t meaningfully benefit from the significant investments their city has made.

Now, The Trust for Public Land is helping Chattanoogans prioritize park investments and community engagement with an eye to closing these gaps in access and opportunity. The goal? Ensuring that all kids growing up in Alton Park, and every neighborhood throughout this city of 180,000, have a safe, healthy, convenient way to get where they’re going—and feel proud, welcome, and at home on their trails.

Jeannine Alday Grogg grew up near the Tennessee River in the 1940s and ’50s but can’t remember ever spending time at the waterfront. Back then, that realm belonged to the booming foundries and factories that gave Chattanooga its moniker, “the Dynamo of Dixie,” and its reputation as one of the most polluted cities in the nation.

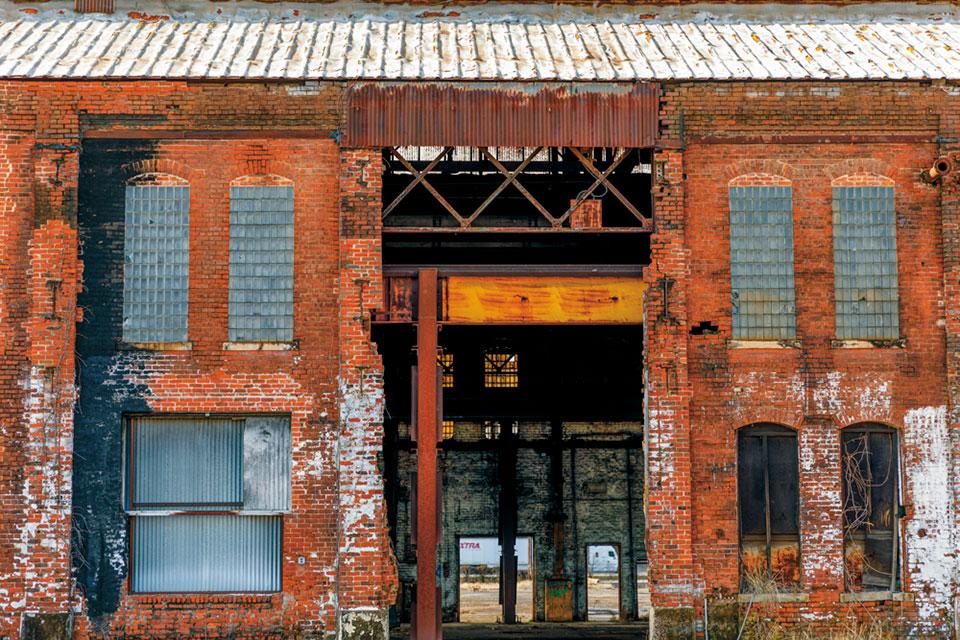

As coal furnaces died out and factories shuttered over the next decades, they formed a long barrier of warehouse hulls, wire fences, and boarded-up windows. Downtown commerce drained to suburban malls, and by the early 1980s local leaders worried about the city’s future. Where had they gone wrong?

“We realized we had turned our backs on our greatest asset,” says Grogg. “The river.”

As chief of staff for the county mayor’s office in the 1980s, Grogg joined the coalition creating a vision for a future riverside park. Throughout the decade, hundreds of people showed up at planning meetings to share their ideas. And in 1989, the first section of the Tennessee Riverwalk opened northeast of downtown. Grogg remembers surveying the crowd that opening weekend, her eyes welling with tears.

“There were people there to exercise, and people there to fish for supper. And I just thought—this, this is what we wanted to do. One of our goals was to bring people together from all walks of life.”

Over the years, the Riverwalk stretched north to the Chickamauga Dam and south into downtown. In 1994, the Trust for Public Land opened an office in Chattanooga to support the expansion. Soon, the organization took the lead on creating the South Chickamauga Creek Greenway, a trail that runs perpendicular to the Riverwalk, reaching 13 miles into the southeastern outskirts of town. Together the Riverwalk and the South Chickamauga Creek Greenway form a 25-mile network of off-street trails winding along waterways, old rail lines, business districts, and residential neighborhoods throughout the metro area.

Today this trail network hosts high-profile events like the Ironman triathlon, which generates approximately $11 million for the city with each race. Music festivals, the Tennessee Aquarium, a children’s museum, and new hotels draw thousands to the waterfront each season. This riverfront revival is a case study for city planners worldwide, who call it the “Chattanooga Way.”

“We’re trying to help our kids to reclaim ownership of these spaces.” Inside the community center at Cromwell Hills, a public housing community in northeast Chattanooga, Latonia Grant points to a big map of the city depicting the two halves of South Chickamauga Creek Greenway. For 25 years, The Trust for Public Land has led the creation of this 13-mile trail, gradually cobbling together and paving abandoned rail lines and vacant lots to form a near-continuous route that cuts diagonally through the city from southeast to northwest.

All that remains is a single one-mile gap, scheduled to be completed later this year. It’s marked on the map by a dotted yellow line—running right past Cromwell Hills.

“The map shows both how extensive the trails are, and how so many neighborhoods are cut off from them, even in the core of town,” says Jenny Park, The Trust for Public Land’s Tennessee state director, tracing a finger around the belt of busy roadways and industrial zones that isolate Cromwell Hills from the rest of the city.

which means gravel trucks and 18-wheelers barrel 50 miles per hour down the road that’s also the main passage for people walking to the nearest grocery store. Grant, the longtime manager of the Cromwell Hills community center, has picked up residents on the side of the road because she is concerned for their safety. Traffic and infrastructure contribute to a sense of alienation for residents, especially kids, seniors, and others who don’t drive. “People here want to be more a part of their community,” says Grant in her office at the community center. “It’s just hard because of how we’re situated.”

That’s why a completed greenway “could be a really big deal for folks here,” Grant says. Residents need safer routes for shopping, getting to Chattanooga State Community College, or commuting to jobs downtown. “It gets us connected to the rest of the city.”

Cool, calm, and connected: Nelson Barrios has a bike commute to aspire to.

“It changes my day. I arrive at work, and I’m smiling,” he says. As he rolls into work flush with endorphins, many of his colleagues enter battle-weary from the morning’s traffic. The interstate interchange in Chattanooga is considered one of the worst bottlenecks in the country, and still, 82 percent of commuters in the county drive themselves to work solo.

Barrios has come to recognize many of his fellow weekday commuters—some in medical scrubs, others in business wear—as they begin and end their workdays. One fellow commuter heading farther up the road is Chris Lykins, who regularly bikes seven miles from his home downtown to his work as a design instructor at Chattanooga State Community College.

The greenery, the views, the $200 million residential development, the direct link to downtown, the sculptures—all are the fruit of decades of effort to carve out public access along a river long obstructed by industrial sprawl.

“We meet people who have chosen to pick up and move close to the Riverwalk,” says Jenny Park, with The Trust for Public Land. “And then we find many longtime residents who have never stepped foot on it, or even heard of it.”

That’s why, Park says, the next frontier of trail building is right in the heart of the city. With the South Chickamauga Creek Greenway nearly complete, Park’s team is turning its focus to creating a series of shorter greenways as Riverwalk “tributaries,” threading deeper into neighborhoods that are cut off from the main stem of the trail by highways, rail lines, or industrial zones.

The Alton Park Connector will follow an abandoned CSX rail line that arcs north of the neighborhood, creating a safe bypass of the five-lane thoroughfare that is currently the main access to the trail.

Dotley said that as news of the connector spreads in the neighborhood, excitement is growing about better access to grocery stores, pharmacies, and jobs in the city’s burgeoning south side. But physical barriers like highways and train tracks aren’t the only hurdles The Trust for Public Land is working with Alton Park residents to overcome.

“It’s not enough to have this extensive trail system if people don’t feel welcome and comfortable once they’re there, or if our parks and public lands aren’t meeting the needs of all communities,” says Jenny Park. The Trust for Public Land has convened advisors from underserved neighborhoods to lead its next stage of trails planning. The organization is also helping with events—from after-school programs to church services—at Southside Community Park, the planned entry point for the Alton Park Connector Trail.

“Alton Park has been its own little bubble, and this finally offers hope that we get to be a part of our city,” Dotley says. “We need our kids to know that their neighborhood is important, but it’s also a part of a greater Chattanooga.”

“I would have never known this trailhead was back here,” said Vivian Lozano, who guided her dog, Gary, to a bend where the women paused to pass around a trail map. They were each there as part of a Trust for Public Land–supported program called Outdoor Ambassadors, which equips community leaders with a broad knowledge of the city’s parks through hikes, paddling trips, and other outings. “We’re sharing some of what we know, and inviting ambassadors to go out and share with their communities—especially those who feel isolated from Chattanooga’s outdoor opportunities,” said Daniela Peterson, an Outdoor Ambassador leader who works for The Trust for Public Land.

That often includes immigrant families, said Lozano. “We all have parents or families back in home countries who are really connected to the land. But somehow in the process of moving here, many of us have lost that,” said Lozano. “I think for most families it’s just understanding where these spaces are, and how to get here.”

While we navigated a flooded section of the trail, Lozano and Peterson told me about an Outdoor Ambassador who’d spent a bunch of time outside before he emigrated from Mexico— but felt less comfortable on the trails around Chattanooga because he never saw anyone who looked like him. “He encountered this common narrative of, ‘We don’t do that, we don’t belong there,’” said Peterson, who moved to Chattanooga from Chile. “We want to break down those social barriers and help people build familiarity and feel welcome on trail.”

I thought back to something Raquetta Dotley told me about her visit to the Riverwalk last year: she pointed out how special it was to see residents in the condos along the river hanging out with her students, and people stopping to let the kids pet their dogs. It’s reminiscent of what Jeannine Grogg saw that first day on the Riverwalk thirty years ago: people of many ages and backgrounds all enjoying a day at the park.