Generations of my mother’s family came from Colorado. As a kid, my heroes included well-known cowboys, pioneers, smoke jumpers, and the men of the 10th Mountain Division. When we visited Clear Creek, Cañon City, or the Western Slope—or ventured east to Colby or Hays—those places brought my childhood heroes’ stories to life.

As we celebrate Black History Month, however, we must acknowledge the stories that were not reflected in those places, the stories of the Black cowboys and settlers of the West whose communities had largely vanished from Colorado’s physical landscape, to say nothing of its collective consciousness, by the time I was studying our state’s history.

One in four cowboys was Black. Thousands of Black “Exodusters” came West seeking their fortunes in the late 1800s. There were 25 Black settlements in Colorado alone, and even more in Kansas. Now, with the exception of one—Nicodemus—these places remain only in a scant few history books and the family stories of their descendants.

Martin Luther King National Historic Site in Atlanta, GA. Photo: Christopher T. Martin

Martin Luther King National Historic Site in Atlanta, GA. Photo: Christopher T. Martin

What would it be like if those homes, community halls, and settlements were still there, illuminating my childhood and those of future generations with the stories of courage, struggle for freedom, and hard work of those who occupied them? What if Ida B. Wells’ legacy had been visible in the landscapes that shaped the narrative that I learned about the West?

History is often thought of as primarily a matter of oral traditions and written records, yet tangible spaces, whether buildings, structures, or properties, also play a critical role in constructing our collective memory. The scarcity of places that evoke Black history isn’t unique to my home state. Of the 95,000 sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places, only 2 percent focus on the experiences of Black Americans, according to the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund. This denies all of us the ability to reflect on, learn from, and honor a more complete view of the past.

Many of the sites that we do have center on the injustices—and horrors—that enslaved African people and their descendants experienced. But as important as it is to highlight those injustices, we also have an opportunity to highlight a much fuller story that emphasizes African Americans as agents in their own story. As Brent Leggs, executive director of the Action Fund, explained in a talk last year at Rutgers University: “It’s true that the Black experience is partly about racial inequality. That’s real. Yet the African American story reveals a rich historical narrative that extends far beyond this history of suffering and marginalization.”

Conserving sites of significance to Black culture and history has long been a part of our work—protecting land and creating parks, with community and equity at the center. Throughout our nearly fifty-year history, we have fought to ensure that all Americans are represented in and connected to outdoor spaces, and that includes the nation’s rich array of historic sites.

Clearly, though, our historic preservation movement has not made sure all Americans can see their racial and ethnic groups’ experiences reflected when they visit historic sites. Black churches, schools, and settlements were not prioritized by agencies and groups calling the shots about what to save. Instead, preservationists focused on the kinds of grand homes, imposing cultural institutions, and august government buildings that were themselves the products of the racially exclusive institutions that dominated American history. Given the other inequities and challenges they faced, Black communities often had neither the time nor the money to advocate for and fund the restoration of Black historic sites. As a result, many sites have been lost to decay or demolition, lending an urgency to protect those that remain. A window is closing, too, on opportunities to tap into the knowledge and elevate the voices of members of the generation that led the Civil Rights Movement.

Photo: Kesha Lambert

Photo: Kesha Lambert

Our most recent Black history project, called Meadowood, saved a 285-acre former tobacco farm in Connecticut where a young Martin Luther King Jr. worked during college summers. King’s time there—his first outside the segregated South—proved transformative, reshaping his worldview and inspiring him to social activism. We are now working with local partners to restore and provide interpretative experiences in the weathered barns still standing on the property.

Meadowood was a fitting bookend to an even more ambitious effort we led over the course of several decades in Atlanta, where we protected more than a dozen properties around Martin Luther King Jr.’s birth home. Today, those properties form a core part of a National Historical Park dedicated to his life and legacy that receives more than a million visitors a year.

Since then we, along with other nonprofits and community partners, have protected more than a dozen other Black historical and cultural sites. In Chicago, we helped the National Park Service acquire the brick homes and warehouses that made up the Pullman railcar company town. In 2015, President Obama designated the area as the Pullman National Monument, commemorating one of the first planned industrial communities and birthplace of the first Black labor union. In Kansas, we are now working to establish a new visitor center at the Nicodemus National Historic Site, which showcases the oldest—and only remaining—Black settlement west of the Mississippi River.

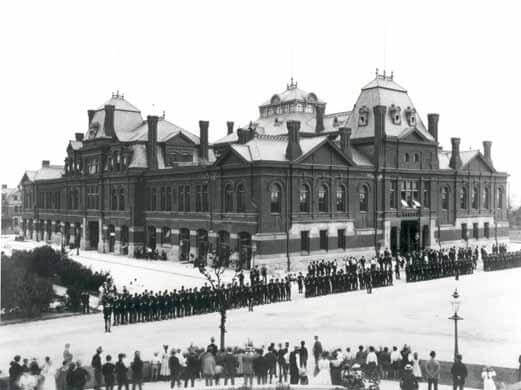

Pullman strikers outside Arcade Building in Pullman, Chicago. The Illinois National Guard can be seen guarding the building during the Pullman Railroad Strike in 1894. Photo: Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project

Pullman strikers outside Arcade Building in Pullman, Chicago. The Illinois National Guard can be seen guarding the building during the Pullman Railroad Strike in 1894. Photo: Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project

Today there is broad awareness that accelerating the preservation of Black historical sites is critical to telling the full story of America. Walking in the steps of a young MLK Jr., sitting in a pew in an African American church, peering into a segregated officers’ quarters, gazing at the rafters of a tobacco barn where Black college students once worked, stepping onto a restored Pullman railcar. Visceral experiences like these—in places we can see and touch—amplify and expand our connection to this country and to one another. Although much has been tragically lost, thousands of important and meaningful sites remain.

Let’s all play our role in making sure that in the future, children in this country have the opportunity to experience historic and cultural sites that tell the full American story.

Diane Regas is president and CEO of Trust for Public Land.

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!