Earthly miracles: preserving a pilgrimage in New Mexico

Earthly miracles: preserving a pilgrimage in New Mexico

The road to the village of Chimayo winds through the foothills of New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains. It’s usually a quiet highway, linking this slow-paced village of adobe houses and rickety toolsheds with the city of Santa Fe 30 miles to the south.

But once a year, in the week before Easter, tens of thousands of people converge on this route—journeying on foot. Their destination is the Santuario de Chimayo, a humble adobe chapel known to some Catholics as the “Lourdes of America.” Inside, pilgrims visit a shrine and gather sandy soil from the floor of a tiny room adjacent to the chapel: the earth here is said to promote healing, even of terminal diseases and permanent disabilities.

Twenty years ago, the well-tended potrero—or pasture—that formed the backdrop to the chapel was at risk. A developer had approached Modesto Vigil, a lifelong Chimayo farmer who owned the property, with a proposal to build a mobile home park behind the santuario. Instead, the Vigil family worked with The Trust for Public Land to protect the pasture, which is now owned by the County of Santa Fe and preserved as open space.

Before the santuario was built in the early 1800s, these peacful potreros were a place of healing for the pueblo people who’d lived in the area for millennia. Photo credit: Don Usner

Before the santuario was built in the early 1800s, these peacful potreros were a place of healing for the pueblo people who’d lived in the area for millennia. Photo credit: Don Usner

“Modesto was an artist. He cared for his potrero with the deep wisdom he’d inherited from countless generations of his family who’d farmed the land before him, and did a superb job,” says Don Usner, a writer, photographer, and Chimayo’s unofficial local historian. Cut by a clear-flowing stream and shaded by towering cottonwoods, the potrero is more than picturesque. “It’s so integral to the experience of the santuario,” Usner says, “as much for pilgrims as for lifelong residents who go to mass at the chapel every week.”

Some say the pilgrimage to Chimayo began in the late 1940s, when a handful of World War II veterans and their families made the trek on Good Friday to grieve for their fallen comrades and show gratitude for their own safe return. Today, 60,000 people of many different faiths and traditions walk to Chimayo during Easter week, making it the largest ritual pilgrimage in the United States.

Most of the pilgrims begin their journey in Santa Fe, walking 30 miles to reach Chimayo. Some come all the way from Albuquerque or Taos, more than 90 miles away, while others may only be able to walk the final hundred yards. The Department of Transportation blocks off a lane of the highway to protect pilgrims from traffic, and locals along the route offer pilgrims food, water, and blessings.

“People walk all the way from Albuquerque, from Taos, from Truchas, from Cordova,” a pilgrim named Orlando Romero told NPR. Romero, in his late 60s, seeks “blessings for my family, the blessings that this place provides.”Photo credit: Flickr user Larry Lamsa

“People walk all the way from Albuquerque, from Taos, from Truchas, from Cordova,” a pilgrim named Orlando Romero told NPR. Romero, in his late 60s, seeks “blessings for my family, the blessings that this place provides.”Photo credit: Flickr user Larry Lamsa

The santuario itself is an adobe structure that dates to about 1813. It was built by one of Usner’s ancestors, Bernardo Abeyta, who led a band of Catholic devotees known as Los Penitentes. According to legend, Abeyta was strolling through the pastures one evening when he saw a light radiating from the dirt. He dug toward the light and uncovered a glowing crucifix, and decided to build a chapel on the site.

“In Bernardo’s letters about the chapel, he never mentioned a miraculous apparition,” says Usner. “He did say that it was a holy site long recognized by the Tewa people, and that the healing dirt legend was established long before Los Penitentes arrived. It seemed like the right place to build a church.”

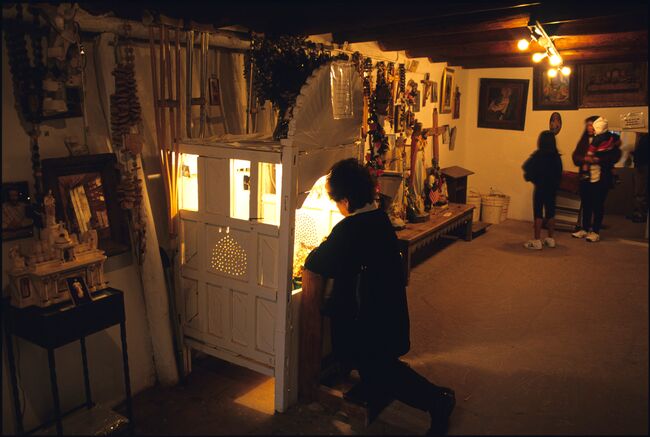

Today, the chapel and its pastoral setting still captivate visitors. Walls in the santuario are covered with notes offering praise and asking for healing for loved ones. A rack holds crutches left behind by pilgrims as a statement on miraculous healing. But for many, the value of the pilgrimage is in the journey. “The act of pilgrimage is highly personalized today. Every person who undertakes it has their own reasons,” says Usner.

Pilgrims leave notes, offerings, and even crutches behind at Chimayo, testaments to faith and gratitude.Photo credit: Don Usner

Pilgrims leave notes, offerings, and even crutches behind at Chimayo, testaments to faith and gratitude.Photo credit: Don Usner

He says for Chimayo residents, the santuario is a bright star in the constellation of a unique local culture that’s thriving, despite challenges.

“Chimayo is one of the most extreme, unusual, quintessential New Mexico places,” says Usner. Many of the town’s 800 residents can trace their heritage back to the Tewa pueblo people and the Spanish colonists who arrived in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the early 1600s. Today, locals practice traditional crafts like weaving, along with more contemporary art forms like lowriding—restoring old cars and painting them with elaborate, colorful designs. Foodies throughout the Southwest seek out the Chimayo chili, a kind of pepper that only grows here, for its smoky, sun-dried heat. Chimayo isn’t far from modern Santa Fe, but as Usner puts it, “it’s another culture entirely.”

“Chimayo gets a bad rap sometimes. Outsiders associate it with drug use, crime, and poverty,” says Usner. “So to have this sanctuary, in such a beautiful setting, and a meaningful tradition that’s admired by the outside world—it’s a point of pride. It can’t be overstated how important it is to remember that, hang on to it, and keep it intact.”

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.