Lisa Brown, a high school math teacher in western Montana, tracks the seasons according to the good things she can harvest from nearby woodlands and forests.

In spring, that’s morels—wrinkly, wild mushrooms that thrive in moist, shady areas. In summer, there are huckleberries, chokecherries, and blackcap raspberries, which she turns into a variety of jams and jellies. Fall finds Lisa and her husband, Scott, gathering firewood as well, enough to heat their house all winter.

“It makes you appreciate the foundation of life, and why you live here,” says Lisa, referring to her ability to access lands for foraging, hunting, and fishing.

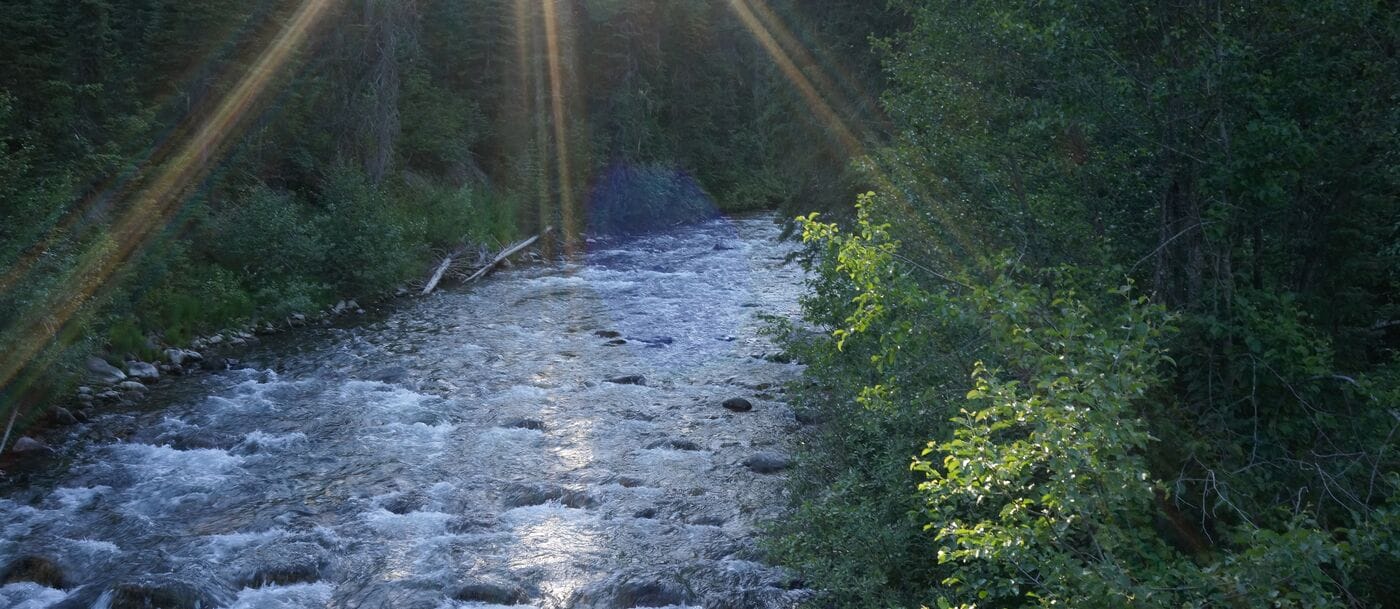

In Montana, with its vast stretches of forests, lakes, and streams, many residents turn to nature to supplement the pantry and refrigerator. Lisa, for instance, hunts elk; the meat of one animal lasts an entire year. She also fishes for kokanee salmon, canning the rosy flesh for future meals.

But the self-reliant, nature-loving lifestyle cherished by Montanans is at risk. People are pouring into the state, snapping up land for second homes. And land owners are selling forests to meet the rising demand for housing.

When that happens, public access to land—for all kinds of recreation, including hunting, hiking, skiing, and birding—is jeopardized. Traditionally, for instance, timber companies with large tracts of land in Northwest Montana have allowed the public to use their properties, but developers and private owners have other ideas.

Join us to support TPL’s work in Montana and across the nation.

“Some of the timberland that’s been purchased—it’s shut off now,” explains Lisa who lives in the town of Plains, about an hour and a half southwest of Kalispell. “Those areas where we used to be able to go and camp; it’s all gated. More than half of the shoreline of one of our favorite lakes is no longer accessible.”

Pressures like these are why Trust for Public Land is stepping up its commitment to protect land in the state. We’ve already secured public access to 600,000 acres in Montana; now, we’ve set an ambitious goal to conserve an additional 200,000 acres over the next three years. Land conservation, with guaranteed public access, is key to ensuring that Montana’s remarkable natural resources remain available to future generations, including Lisa’s grandchildren.

Lisa Brown enjoying the great outdoors. Photo: courtesy of Lisa Brown

In fact, she has already instilled a love of berry picking, and eating, in her six grandchildren. “Huckleberry pancakes are a favorite of our grandkids,” she notes. “The youngest will be 2 next month, and the oldest will be 16. They are not all mushroom fans. But they all love the berries.”

Lisa’s favorite berry is the blackcap raspberry, which she describes as darker than a raspberry and sweeter than a blackberry. “They are called blackcaps because they are so purple that they are almost black,” she explains. “You find those in late July or early August on bushes in old logging areas. Around Thompson Falls, if you go back into the old logged areas before the new trees take over, you can pick 10 or 15 gallons of blackcaps in a good year.”

The payoff? “You make jelly, juice, jam—anything you would do with a raspberry,” she says.

Morels are more of an acquired taste. You don’t forage morels; you hunt them. (At least that’s the term favored by aficionados.) And Lisa has hunted them since childhood. With a taste described as earthy and nutty, morels are found in woodlands, especially under decaying ash and elm trees. They emerge in previously logged or disturbed areas, as well as lands raked by wildfire.

“It’s pretty easy to find them now, with the amount of forest fires we’ve had,” Lisa points out. “It’s the instant crop that pops up after a fire—as long as you have the right environment. And western Montana is a great environment for morels.”

In May and June, Lisa will harvest morels she finds along creeks and trails while she is out fishing or hiking. “When you get into a good patch, you might see 50 to 100 morels within a hundred square feet,” she says. In other words, it can take a lot of searching to find only a small amount. “But a half pound goes a long way,” she attests. “Sautéed morels with butter and garlic are the best.”

As her grandchildren grow into adults, she hopes to teach them the ways of the Montana woods and mountains. In a culture increasingly oblivious to the source of its food, the ancient practices of foraging and hunting connect us to nature and deepen our appreciation for its many gifts—something Lisa is well aware of.

“There’s nothing like walking downstairs, going into the pantry, and asking yourself, ‘Do I feel like chokecherry jelly or huckleberry jam this morning?’” she says. “‘Or canned salmon or elk tonight?'”

There’s also nothing like knowing you created those stores, an act that depends on access to land.

Lisa W. Foderaro is a senior writer and researcher for Trust for Public Land. Previously, she was a reporter for the New York Times, where she covered parks and the environment.

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!