In Los Angeles, a new park by the people, for the people

In Los Angeles, a new park by the people, for the people

A flock of kites has taken up residence in the sky over Los Angeles. You can find them out there on any sunny Saturday, held aloft by the steady breeze off the Pacific Ocean, and trace their strings to the rambling lawn at the Los Angeles State Historic Park. Since its grand opening this spring, California’s newest state park has quickly become a mainstay for kite pilots—not to mention picnickers, joggers, yogis, Frisbee-throwers, and tai chi practitioners, all drawn to this 32-acre oasis in the heart of the city.

“When I go to the park, it already feels like a given—like it’s so well-loved that what it is now is the only thing it ever could have been,” says artist Rosten Woo, who lives nearby. When he was commissioned to create an art installation for the new park, he started by reading up on its history—and was surprised by what he found. “I really couldn’t believe how so much work, struggle, and effort got poured in by so many people over the course of decades to make this park happen,” he says. “It’s a remarkable story.”

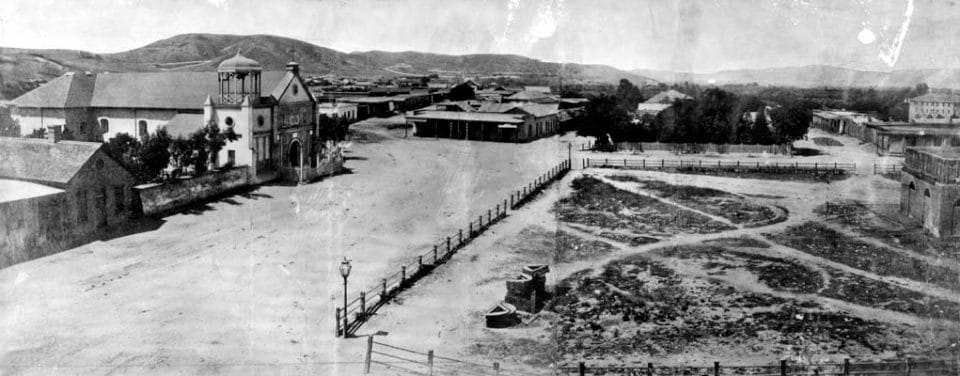

El Pueblo de Los Angeles in 1869. Archaeologists uncovered traces of the ditch that settlers dug to bring water from the Los Angeles River to the pueblo running through the new park.Photo credit: Los Angeles Public Library

El Pueblo de Los Angeles in 1869. Archaeologists uncovered traces of the ditch that settlers dug to bring water from the Los Angeles River to the pueblo running through the new park.Photo credit: Los Angeles Public Library

Where that story begins depends on who you ask. “This piece of land has been the nexus of so many forces that shaped our city,” says park deputy superintendent Stephanie Campbell. Back when the Los Angeles River was still wild, this was a broad, green valley bursting with wild roses and grapevines. The Tongva/Gabrieleno people had made it their home long before Spanish settlers established a pueblo less than a mile away—a settlement that would become the city of Los Angeles. What’s now the park was once farmland, which is why some locals know it as “the Cornfield.”

In the 1870s, the Cornfield became the terminus for the Southern Pacific Railway. “For much of the 20th century, while L.A. was growing from a small town to the multinational city it is today, this was a hub of commerce and industrial growth,” Campbell says. “The Cornfield played an important role in that development.”

In the 1870s, the Cornfield was the terminus for the first passenger rail in Los Angeles. “Anyone coming to L.A. from the East or Midwest was coming by rail, and this was the first place they would disembark and encounter the West Coast,” says Campbell. Photo credit: Bruce Petty and CSRM Locomotive and shop workers

In the 1870s, the Cornfield was the terminus for the first passenger rail in Los Angeles. “Anyone coming to L.A. from the East or Midwest was coming by rail, and this was the first place they would disembark and encounter the West Coast,” says Campbell. Photo credit: Bruce Petty and CSRM Locomotive and shop workers

As central Los Angeles grew and filled in with working-class families, the largely immigrant population more than once found itself on the short end of development plans. Residents of Chavez Ravine, a pastoral neighborhood overlooking the river, were evicted from their homes to make way for Dodger Stadium in the 1960s. Chinatown was relocated to build a train station, and the “new” Chinatown—which borders the park to the south—is one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the city. Until this year, most of Chinatown’s 25,000 residents did not have a single park within walking distance of home.

So by the time the last trains had pulled out of the decommissioned railyard in the late 1990s, local residents were ready for a change. When a real estate firm bought the site and announced plans for a large warehouse complex, neighbors knew they were in for a fight to secure the public green space they’d long needed. Chi Mui, a legendary Chinatown organizer, assembled a coalition of more than 30 groups—like the Mothers of East Los Angeles, the Latino Urban Forum, Save the Bay, and Tree People, and national conservation and religious organizations—into the Chinatown Yard Alliance to tackle the formidable task of halting development plans already backed by the mayor and several city council members.

By the late 1990s, the Cornfield was a vacant railyard with acres of potential to connect central L.A. residents with nature—but a real estate firm had plans to turn it into a warehouse development.Photo credit: Rich Ried

By the late 1990s, the Cornfield was a vacant railyard with acres of potential to connect central L.A. residents with nature—but a real estate firm had plans to turn it into a warehouse development.Photo credit: Rich Ried

The alliance also relied on everyday people from nearby neighborhoods—like Solano Canyon and the Meade Homes, the city’s oldest public housing development. Park advocate Arthur Golding got involved through his early work to restore the Los Angeles River, which runs just north of the site. “This piece of land had huge potential to help people reconnect with nature right in the heart of the city,” Golding says. “You think about the inequitable history of the area’s development, and that Chinatown and the other neighborhoods surrounding the area have so few places to experience nature. Well, here was a big piece of land right on the river that was already open space, that had always been open space. We thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if this were a park?’”

Over the next three years, the Chinatown Yard Alliance organized protests and fought the developer in court. In the face of the community’s opposition, the warehouse plan that once seemed inevitable began to flounder. That’s when The Trust for Public Land approached the property owner with an alternative: sell. “When the legal issues … became an obstacle for [the developer], they responded to the idea of a community park,” said The Trust for Public Land’s Larry Kaplan at the time. In 2001, Kaplan and his team negotiated a sale and helped transfer the land to California State Parks.

“I wanted to emphasize that this park didn’t happen by accident. The signs undercut the idea of a park being something that the government does for you. It’s for you, yes, but people like you worked so hard to make it happen,” says Woo of his installatio.Photo credit: Frank S. Bathis

“I wanted to emphasize that this park didn’t happen by accident. The signs undercut the idea of a park being something that the government does for you. It’s for you, yes, but people like you worked so hard to make it happen,” says Woo of his installatio.Photo credit: Frank S. Bathis

Earlier this year, we joined thousands of Angelenos who turned out to celebrate the grand opening—at last—of the Los Angeles State Historic Park. On the site of the old railyard, the downtown skyline now rises dramatically over groves of fruit trees, open lawns, and a restored wetland. “Our city’s big parks are all up in the mountains, and they’re great,” says Rosten Woo. “But Los Angeles has never had a big ‘Central Park’ down here where a lot of people actually live—and now we do.”

Woo’s installation for the new park draws inspiration from the people who fought for decades to realize their vision of a more livable community. The colorful, multilingual signs recall the placards carried by neighbors protesting the warehouse development back in the 1990s. They’re simple, with a deliberate, handmade aesthetic, and they stand askew in a cluster in a corner of the park. The largest declares,“A Park Is Made By People.”

“I wanted to create something that would honor the original rabble rousers, like Chi Mui and Arthur Golding, and remind newcomers of what it took to create this place,” says Woo. “It’s easy to think of parks as something pleasant that the government does for you—people don’t always think of themselves as having an active role to play. But this would be warehouses today if everyday people hadn’t gotten deeply involved.”

This raw, beautiful landscape in Southern California is home to Indigenous heritage sites, and it provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species. Urge the administration to safeguard this extraordinary landscape today!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.