Water-smart park points to a drier future for a neighborhood plagued by floods

Water-smart park points to a drier future for a neighborhood plagued by floods

This year’s Super Bowl played out at the new Mercedes-Benz Stadium in downtown Atlanta, a gleaming 30-story structure that opened in 2017.

The new stadium is visible from pretty much anywhere in Vine City, a residential neighborhood on the edge of downtown Atlanta. It looms large from the corner of Vine Street and Joseph E. Boone Boulevard, site of the future Cook Park. Once complete this summer, the new city park will have features like a dynamic playground, an outdoor classroom, and a rock climbing wall. And beyond providing a much-needed public space in a neighborhood where safe places to play are too few and far between, Cook Park will also help control flooding, a persistent problem for generations of neighborhood residents.

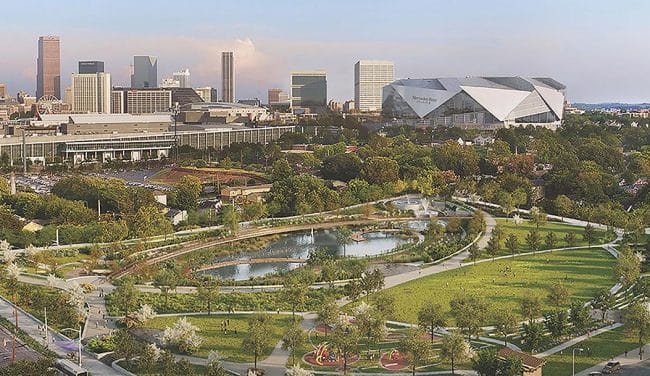

Mercedes-Benz Stadium gleams on the skyline in Vine City. We’re working to create a brand new city park that will reduce the risk of flooding on Atlanta’s historic Westside.Photo credit: Christopher T. Martin

Mercedes-Benz Stadium gleams on the skyline in Vine City. We’re working to create a brand new city park that will reduce the risk of flooding on Atlanta’s historic Westside.Photo credit: Christopher T. Martin

Vine City and nearby English Avenue have long been home to African American academic, religious, political, and business luminaries. The area boasts four prominent historically black colleges and universities. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. lived here, alongside fellow civil rights leaders Julian Bond and Maynard Jackson.

But today, the neighborhood has among the lowest incomes and highest crime rates in Atlanta. Abandoned buildings and vacant lots outnumber occupied homes. Despite its proud legacy, more recent memories reflect the outcomes of decades of disinvestment and inequality, says Tony Torrence, an environmental activist who’s lived on the Westside for decades.

One of those memories is of a rainstorm in 2002 that sent a flash flood tearing through Vine City and English Avenue, destroying dozens of homes and damaging hundreds more. “People were swimming out of their homes,” Torrence recalls. “Trying to climb out of windows. We had to drag people out of their houses.” In the aftermath, the City of Atlanta razed 60 homes, and relocated hundreds of residents.

Torrence says the 2002 disaster was an outlier, but English Avenue and Vine City are no strangers to high water. “We’re on low ground here,” he explains. “And right downstream of downtown, which is all paved over. So all the rain that falls downtown funnels right into the Westside.”

Catastrophic floods like the one in 2002 pose immediate risks to life and property, but Torrence says the long-term effects of badly managed stormwater are no less hazardous: “The ground slumps. The foundations of your house crack. The roof leaks, and rain gets in. Then you have mold and mildew, and that stirs up your asthma. If your health isn’t good, it’s harder to go to work,” he says. “So you see how the stormwater situation in this neighborhood is contributing to some of the social challenges that we’re facing.”

Torrence has long worked to spread the word about the health hazards of stormwater, and connect his neighbors to resources to protect themselves. But addressing the causes of flooding—like an archaic combined sewer and stormwater system that can’t handle bigger, more frequent rainstorms—call for big investments, says Cory Rayburn, Watershed Manager with the City of Atlanta.

“Instead of only building big vaults and tunnels, which are expensive and really only serve the aim of flood control, we’re also looking everywhere in the watershed for places we can use parks and natural systems to manage flooding and water quality,” says Rayburn. Using “green infrastructure” reduces flood risk, while providing all the other benefits of a great city park.

The new Cook Park will have a specially engineered pond to collect and filter stormwater, reducing the risk of flooding throughout the neighborhood. The approach has worked well across town at the Historic Fourth Ward Park, which opened in 2011.Photo credit: Darcy Kiefel

The new Cook Park will have a specially engineered pond to collect and filter stormwater, reducing the risk of flooding throughout the neighborhood. The approach has worked well across town at the Historic Fourth Ward Park, which opened in 2011.Photo credit: Darcy Kiefel

One of the best examples of this approach is Cook Park, which is being built on the same ground as the homes that were destroyed in the 2002 flood. Today, after years of activism by neighborhood residents like Torrence, we’re helping transform those 16 acres into a state-of-the-art city park, engineered to absorb millions of gallons of stormwater, through engineered green space and a retention pond. “The people who live in these low-lying areas have been the ones advocating for this park the longest,” says Torrence. “It started with community groups saying, ‘Hey, we have to do this. These floods are impacting our lives.’”

Atlanta’s political and corporate leaders agree. “When the mayor announced the location of the stadium, that gave city leaders a renewed imperative to invest in and lift up Westside neighborhoods nearby,” says John Ahmann. He’s CEO of the Westside Future Fund, a group working to revitalize English Avenue and Vine City through targeted, coordinated investments and programs. Addressing flooding on the Westside is high on Ahmann’s list of priorities—and green infrastructure projects like Cook Park are an important part of the solution.

The new Cook Park will be part of a coordinated effort to revitalize Vine City, where Martin Luther King Jr. lived as an adult. “Our vision is to develop a community that Dr. King would be proud to call home,” says Ahmann with the Westside Future Fund.Photo credit: HDR, Inc.

The new Cook Park will be part of a coordinated effort to revitalize Vine City, where Martin Luther King Jr. lived as an adult. “Our vision is to develop a community that Dr. King would be proud to call home,” says Ahmann with the Westside Future Fund.Photo credit: HDR, Inc.

“We’re working toward a shared vision of a healthier, more equitable, more prosperous future on the Westside, which will be hard to do if environmental justice issues like flooding persist,” says Ahmann. “The stormwater problems in this neighborhood are tied to health, they’re tied to property values, they’re tied to public safety and housing availability. You can’t address any of these challenges in isolation.”

One-third of Americans, including 28 million children, lack safe, easy access to a park within a 10-minute walk of home. Urge your senators to pass the Outdoors for All Act to create parks and enhance outdoor recreational opportunities!

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.

See how our supporters are helping us connect people to the outdoors across the country.