The Trust for Public Land has been transforming schoolyards for over 25 years. We have worked with more than a dozen school districts around the country and have successfully created nearly 300 Community Schoolyards to date. The guidance in this report comes from multiple dedicated staff who have decades of experience on team building, designing, constructing, and stewarding Community Schoolyards. We have assembled the best guidance from these to help you navigate the process of transforming an existing underutilized schoolyard into a vibrant community schoolyard.

Community Schoolyards are a center for health and climate resilience and a hub for equitable community cohesion. In order to achieve this standard, they need to be green, open to the community and involve the school and community in design and activation. A successful community schoolyard is not a product, but a process.

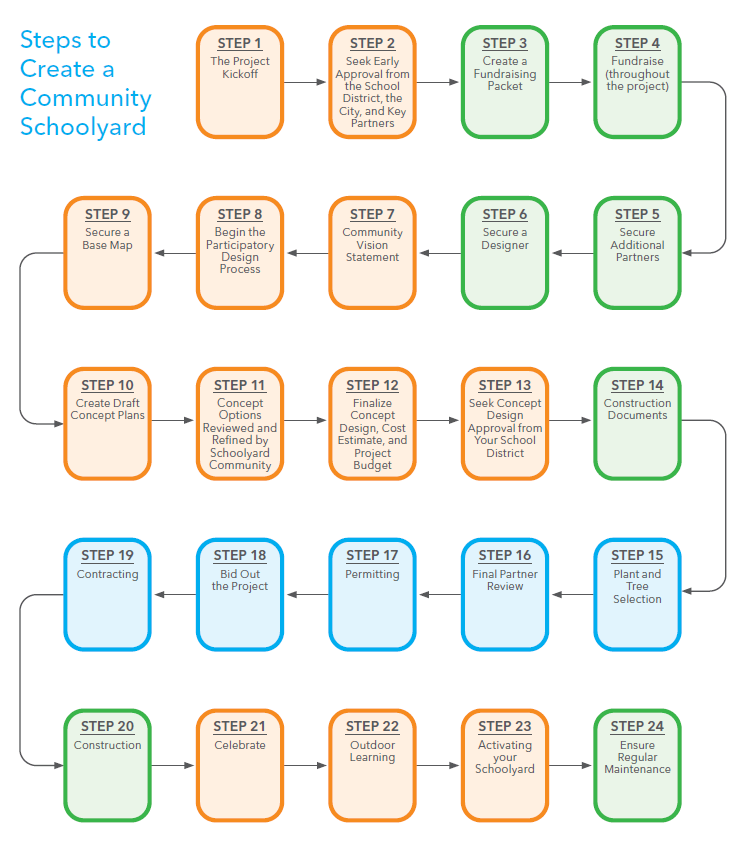

The process for creating a successful community schoolyard is outlined in detail in the following pages.

Many communities choose to remove some asphalt from a schoolyard and replace it with trees, plants, seating, ponds, or gardens. Community Schoolyards often include pollinator gardens, stormwater capture, traditional play equipment, nature play areas, edible gardens, trails, and trees and shrubs. Some schools create outdoor classrooms with chalkboards, tables, sinks, and large seating areas where teachers can ead lessons outdoors. In other cases, the school community may identify the need for calming spaces where children can relax or de-escalate. A range of approaches can be integrated to create healthy and environmentally sound spaces.

America’s typical public schoolyard is, sadly, often a sea of asphalt, perhaps with a few cracks sprouting weeds. Bare schoolyards bake under the hot sun. They flood during downpours. Some have little to no play equipment, and rarely inspire active, creative play. Educational leaders have shared that the condition of the schoolyard correlates with student behavior and attendance rates.

When you create a community schoolyard, you improve the educational setting and thereby educational outcomes, you make your school and community more resilient to climate change, you improve opportunities for physical and mental health and you create a place that will bring the school and community together.

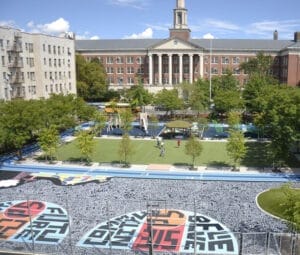

When community members and stakeholders partner to build a community schoolyard, they can transform a space. Check out this before-and-after shot from New York’s School of Science and Technology/School of the Performing Arts (Brooklyn, New York’s P.S. 152/315K). © Maddalena Polletta

Park access can sound like a tricky concept, but it is actually pretty simple. Can a person walk to a park from their home in 10 minutes or less? If they can, then they have park access. Why 10 minutes? Research has shown that 10 minutes is about the distance most people are willing to walk.

Through The Trust for Public Land’s 10-Minute Walk® Campaign, mayors all over the country have agreed to work toward the shared goal of providing park access to 100 percent of their residents within a 10-minute walk of their homes. This is an ambitious goal that will provide close-to-home parks for millions of people, but is it realistic? The process of building a new park can be expensive and slow, particularly in areas where land is scarce and expensive.

This is where Community Schoolyards can help. Many schools choose to make their Community Schoolyards open to the public, particularly after school hours and on weekends. When these schools are in neighborhoods without adequate park access, cities can significantly increase their park access and the multiple benefits that parks have to offer. Since school districts are often one of the largest landowners in cities and much of their exterior spaces are asphalt expanses, this is a big opportunity to create a community schoolyard.

One hundred million people people lack access to a park within a 10-minute walk. If all schools had a community schoolyard, 20 million more people would gain access to a park within a 10-minute walk.

In neighborhoods without an existing park, Community Schoolyards™ can provide access to outdoor recreation.

© Jenna Stamm

Absolutely! Across the country, passionate community members are making a major impact by improving their local schoolyards and parks. It will take hard work, collaboration, and perseverance, but if you follow the steps outlined in this guide, you can make your community schoolyard project a reality.

The steps below are organized chronologically, though some steps can move forward at the same time. We recommend that you read through the entire guide and adapt the process to meet your particular situation. Please note that while there are less intensive improvements that a group of volunteers could make to a schoolyard, this guide outlines the process for a major schoolyard renovation project, requiring a professional designer, contractor, and likely a fundraising plan to ensure that you start with an adequate budget. This stepper guide provides all steps in the process to create a Community Schoolyard, however each organization will have different levels of experience and capacity to take on these steps. Use the guide below to decide which of the three team types best describes your group.

You can do this! © JENNA STAMM

Limited Project Development Experience

![]()

Limited Project Development Experience

- Your group has a vision, but is not formally organized.

- Your group has experience organizing diverse groups of people.

- Your group has completed small projects (e.g., installed garden beds, organized school events, or hosted fundraisers).

Considerations

If your schoolyard team is an informal group, it can be helpful to seek “umbrellaship” under existing trusted 501(c)(3) organizations, such as the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) or other community-based groups equipped to manage and receive funds (see Step 1a). Nonprofit status will allow your group to bring in taxdeductible donations and solicit grants. If you choose not to work under an existing nonprofit at this stage, your team should focus on organizing the community around the project tasks described in orange. Additionally, you should seek to partner with a nonprofit with project development experience or advocate for your school district to take on the roles outlined in the green and blue highlighted tasks.

Moderate Project Development Experience

![]()

![]()

Moderate Project Development Experience

- Your team has a vision and experience organizing diverse groups of people.

- Your team is led by an existing nonprofit, organized under 501(c)(3) of the U.S. tax code.

- Your team leader has project development experience, including the holding of professional design contracts.

Considerations

If the statements above apply to your group, and you have school district approval, your team has the credentials, skills, and experience to complete the orange and green colored tasks. Additionally, you should advocate for your school district to take on the roles outlined in the blue colored tasks.

Extensive Project Development Experience

![]()

![]()

![]()

Extensive Project Development Experience

- Your team is led by an existing nonprofit, organized under 501(c)(3) of the U.S. tax code.

- Your team leader has experience with holding professional design contracts, public bidding, and managing the construction process for school district projects.

Considerations

If the statements above apply to your group, and you have school district approval, your schoolyard team has the credentials, skills, and experience to complete the orange, green, and blue colored tasks.

You will see these three colors used for section headings throughout this guide. For example, on page 14, STEP 6: SECURE A DESIGNER is written in green. This indicates that this step should be carried out by a Type 2 or Type 3 team, while Type 1 teams should look to partner with a more experienced organization before getting started.

You will see these three colors used for section headings throughout this guide. For example, on page 14, STEP 6. SECURE A DESIGNER is written in green. This is a reminder that this step should be carried out by a type 2 or type 3 team, while type 1 teams should look to partner with a more experienced organization before getting started.