Along the Southern edge of San Francisco, the last undeveloped stretch of the India Basin shoreline is being transformed into a 10-acre waterfront park.

Taking shape along a newly constructed pier is Lady Bayview, a 5,500-square-foot image of a female figure whose hands encircle a glittering sphere. She is dressed in a swarm of shifting wind barbs and ships that represent the site’s layered history of innovation, perseverance, and community. Artist Raylene Gorum, whose family once lived in the neighborhood, was selected by the San Francisco Arts Commission to create a public artwork for the park. Gorum’s Lady Bayview is intended as a talisman that reflects the community’s history and the legacy of five women who sought to save it. When complete, Lady Bayview will be visible from Google Earth.

Visibility is what generations of women in Bayview–Hunters Point have fought for in a neighborhood marginalized by physical isolation and racial discrimination.

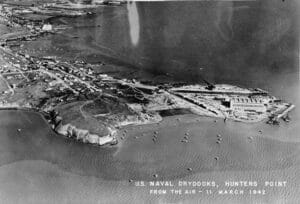

The U.S. Navy dry docks at Hunters Point, as seen from the air in March 1942. Photo: San Francisco Public Library

Historically, Hunters Point was known for its scow schooners, flat-bottomed boats built there in the 1870s. The shipyard was converted to a U.S. Navy facility in 1940 to fuel the World War II defense industry, bringing many new jobs. In 1942, the San Francisco Housing Authority constructed a massive development to temporarily house 14,000 naval dockworkers and their families on Hunters Point Hill. Some 40,000 Black people migrated to the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1940s—many of them settling in the Bayview–Hunters Point neighborhood—seeking work and escape from the prejudice of the Jim Crow South.

Among those migrants were the “Big Five,” commonly identified as Elouise Westbrook, Ruth Williams, Bertha Freeman, Osceola Washington, and Julia Commer. Other notable community leaders, including Marcelee Cashmere, Ethel Garlington, and Essie Webb, have also been considered part of the group. Although the members of the Big Five are vague, it’s clear that their work has been taken up by many women—then and to this day.

One of their biggest battles was the fight for affordable housing. Post-war, the barracks weren’t upgraded to support long-term housing needs. In 1948, just six years after it was built, the development was condemned. However, some 650 families were still living in it more than two decades later.

Ruth Williams coauthored a report for the Redevelopment Agency in which she describes the broken state of the neighborhood, saying, “The 125-acre area is devoid of amenities. One must go as far as six or seven blocks to get the basic grocery shopping. Schools are deficient, the recreation facilities are limited, and the area is bleak and forbidding. Of course, in such run-down housing with leaking roofs, sagging foundations, rotting plumbing, rodents and vermin, the residents can have little respect for their area. But they have great confidence in getting their community rebuilt to suit their needs.”

Living conditions in Bayview–Hunters Point were not unusual in American cities. In The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein recounts how redlining, combined with restrictive covenants and other racially biased housing policies, prevented Black people from owning private housing in many cities and segregated public housing facilities. These legal forms of discrimination created “Black ghettos,” that were consistently deprived of resources, Bayview–Hunters Point among them.

Donate to support our work in California, including India Basin Waterfront Park.

As described in Rachel Brahinsky’s The Making and Unmaking of Southeast San Francisco, the Big Five are legendary for their fight to bring access to education, job opportunities, decent housing, and a healthy environment to Bayview–Hunters Point. They led the movement for racial justice in the 1960s after decades of segregation and disinvestment made living conditions in their community intolerable.

As conditions worsened, tensions rose. In 1966, a white police officer shot and killed a Black teenager as he fled the scene of a car theft. A protest erupted, demanding the officer be charged with murder.

Governor Pat Brown imposed martial law, and the National Guard patrolled neighborhood streets. Locals were distressed by the hostile occupation of their neighborhood and appalled that the city’s reaction was not to right the injustice of a child killed, but to criminalize the neighborhood.

After the uprising, Bayview–Hunters Point gained national attention. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson’s Kerner Commission surveyed riots in 23 cities. As framed by New York Mayor John Lindsay, the commission’s report indicted American race relations, saying “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

Clay Risen describes these events in his book, A Nation on Fire. Despite the loud call to expand national programs aiding Black communities, including Bayview–Hunters Point, federal politicians did not heed them. Instead, Richard Nixon made the protests a rallying point in a presidential campaign that stoked white fears of Black violence—calling for “law and order” rather than social programs.

“If you are from Hunters Point, you get no chance at all.”

— Osceola Washington

It was amid this volatile political climate that the Big Five traveled to Washington, DC, to lobby Housing and Urban Development (HUD) officials to fund new housing in their community. Both State Senator George Moscone and Director of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency Justin Herman had previously failed in securing these investments. The Big Five were successful. They returned to San Francisco with a promise from HUD of $40 million for affordable housing. It was an extraordinary victory for Bayview–Hunters Point.

“It’s been a long struggle, a long struggle.”

— Julia Commer

Their efforts didn’t stop there. The Big Five demanded that the residents of Bayview–Hunters Point shape the new investments in their community. They sought to reverse long-term patterns where city policies and civil servants “do for you instead of doing with you,” in the words of Osceola Washington.

“We want to have a real part in planning our area. We don’t pretend to have the answers, but we know what we want. One thing we want is for you to recognize us as partners in the planning process.”

— Collaboratively Planning at Hunters Point (Report co-authored by Ruth Williams for the Redevelopment Agency)

“In Hunters Point, we are not only trying to build good houses, but we are also trying to build a better image where we have that cooperation and communication with the other part of the city.”

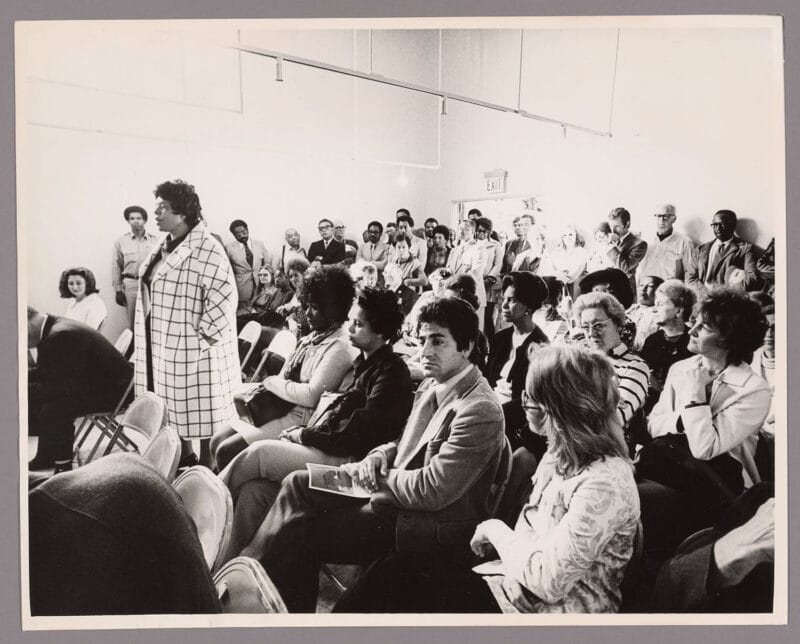

Photo: Joe Rosenthal/UC Berkeley Bancroft Library

The Big Five secured investments, created opportunities, and demanded leadership—bringing dignity and voice to their marginalized neighborhood. In a country that continues to deny Black people and neighborhoods equality, they began a fight to remedy their oppression. Together, they triumphed over odds that were stacked against them. This legacy of self-determination and insistence on partnership with San Francisco’s governors, advocates, and people has been lasting. It courses through the efforts shaping Bayview–Hunters Point today.

“I think it is a great honor for these people that they can say ‘I have it myself and I don’t have to wait for a handout.'”

— Bertha Freeman

These effort are directed by the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department, Trust for Public Land, and the San Francisco Parks Alliance, and the A. Philip Randolph Institute San Francisco, and created in partnership with the Bayview–Hunters Point community. As India Basin Waterfront Park takes shape, Trust for Public Land is supporting a process in which the community of Bayview–Hunters Point directs their neighborhood’s development. It has resulted in the creation of an Equitable Development Plan that aims to guide resources and benefits to long-term residents.

In From the Ground Up, TPL California State Director Guillermo Rodriguez makes clear, “You can’t have a true community engagement process if you’re not listening to the whole story. We set out a [metaphorical] picnic blanket and invited folks to bring their ideas to it. We needed to listen, hear, acknowledge, and provide a platform for creating a bigger vision. We wanted to understand the community’s interest in the entire waterfront. Although we may not be able to solve it all ourselves, we can certainly bring the people who have answers to the picnic blanket to sit with us.”

“You can’t have a true community engagement process if you’re not listening to the whole story.”

— Guillermo Rodriguez, TPL’s California state director

The work to make Bayview–Hunters Point equitable is not over. The charge the Big Five began more than 60 years ago has been renewed by many since. It has been sustained by generations who have continued to uphold their legacy and reinforce their commitment to the people of their community. Today, as a talisman is built to acknowledge these women, their efforts will be visible not only to their neighborhood, but to all who seek a guide to community leadership.

This is a two-part article written by Alison Sant, author of From the Ground Up: Local Efforts to Create Resilient Cities (Island Press, 2022). Part II features the legacy of the Big Five and the stories of community leadership shaping Bayview–Hunters Point today as the construction of India Basin Waterfront Park galvanizes new opportunities for long-term residents.

The Big Five of Bayview

Click on the images below to see videos and articles about the Big Five.

Julia Commer was known as an advocate for housing and schools. Her family was one of the first to move into the neglected housing barracks on Hunters Point Hill. After years of advocacy, when the project was demolished to make way for new housing, she said, “It’s been a long struggle, a long struggle.” Today, Commer Court on Hunters Pont Hill is named after her.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.