Don Hamann knows a thing or two about forests. A logger and longtime resident of Butte Falls, Oregon, he has watched over the past 40 years as the area’s timberlands—its main economic driver—were bought and sold and full-time local logging jobs transitioned to contract jobs. He has also witnessed the rising interest in ecotourism, with backcountry hiking and mountain biking gaining new adherents across the Pacific Northwest.

So when the town of Butte Falls, population 450, had the opportunity to purchase the 430-acre forest surrounding the municipality from the timber company that owned it, residents asked Trust for Public Land to help arrange the acquisition. TPL also hired a consultant to draft a forest management plan. Adopted by the city council, the plan calls for reducing the risk of wildfire by thinning trees and clearing brush, as well as planting a variety of native tree species to avoid the devastation wrought by invasive pests. A recreation plan is also underway, with the city eager to reap the benefits of the forest’s scenic beauty—along with its potential for hiking, mountain biking, and fly fishing.

Hamann was on board from the jump. Not only does preserving the forest as a public asset provide a shot of adrenaline to the ailing economy; it also protects Butte Falls from the ever-growing threat of wildfire.

“We have a plan that maps out all of the highest risk communities in the state for wildfire, and Butte Falls is bright red,” says Kristin Kovalik, TPL’s Oregon state program director.

“This forest is a key piece for protecting our community from a catastrophic wildfire,” Hamann points out. “That is our main concern—fire. So doing fire resilience work automatically moves us to an older forest succession, which fits well with ecotourism, and everything comes together.”

— Don Hamann, logger and longtime resident of Butte Falls, Oregon

Helping towns buy so-called community forests—so that the benefits accrue to residents rather than far-flung real estate investors—is just one part of Trust for Public Land’s wide-ranging conservation work. Over the past 50 years, we have partnered with urban and rural communities to protect more than 3.7 million acres of land, from the rugged coast of Hawai‘i’s Big Island to the fir forests of Oregon to the gentle banks of Atlanta’s Chattahoochee River.

But David Patton, associate vice president for TPL’s national Lands initiative, is quick to point out that we don’t conserve land for its own sake. Protecting forests, grasslands, working farms, mountain peaks, wetlands, and viewsheds is a powerful way to deliver social impact in the form of health, environmental, and economic benefits for urban and rural communities. According to Patton, when done thoughtfully, land conservation that also guarantees public access is so effective because it promotes equity, ensuring that towns and cities can reap the benefits of close-to-home outdoor access.

In fact, connecting environmental stewardship with social justice has been one of TPL’s notable differentiators from the very beginning. “As you go through the years, so many great projects at TPL have a similar story: there was a threat to a landscape that people liked to use, and the community called up Trust for Public Land to ask if we could help,” says Patton.

At the same time that we do this work, we are aware of and committed to acknowledging and rectifying centuries of injustice that displaced tribal and Indigenous people from their homelands and historically left them out of conservation efforts across the United States. Trust for Public Land seeks opportunities to restore sovereignty to Indigenous communities and their ancestral lands.

The need to intentionally and inclusively protect America’s iconic landscapes and historic sites has never been greater. According to the United States Forest Service, every day an estimated 6,000 acres of open space in the United States are converted to other uses. The agency’s definition of “open space” includes any property that is devoid of buildings, whether publicly or privately owned, such as forests, grasslands, farms, deserts, mountains, ranches, rivers, and parks.

Even before the pandemic, outdoor recreation was increasing, putting pressure on existing open spaces. But COVID-19 nudged many more people into parks and wilderness areas. The outdoors beckoned Americans who felt cooped up during government lockdowns and offered a reasonably safe way to socialize. “Over the past five years, recreation has become an important outlet for people for social and emotional health,” Patton says. “But we are seeing impacts to the user experience and impacts on the landscape.”

Emphasis: Equity. Unlocking the Power of Place to Create Community Cohesion

In Georgia, Trust for Public Land is helping to expand outdoor access along 100 miles of the Chattahoochee River, which flows through metropolitan Atlanta.

A study commissioned two years ago by the Chattahoochee Working Group, led by Trust for Public Land, called for a 100-mile greenway connecting the communities along the river and greater Atlanta. Among the priorities: making the river accessible for people of all backgrounds, abilities, and ages, and improving the ecological health of the river basin.

With towns and counties undertaking a spate of new projects, Trust for Public Land is focused on three miles of riverfront across from Atlanta. There, we will undertake a showcase project featuring parks, trailheads, and overlooks, all connected by the greenway. We are also creating a 48-mile camp-and-paddle trail, with boat launches and campsites, that will provide first-time river access for the city of Atlanta.

The northern half of the 100-mile greenway runs through suburban communities where there is currently abundant access, explains Walt Ray, TPL’s Chattahoochee program director. “It’s the southern half that has traditionally lacked any access and that also coincides with diverse communities,” Ray says. “So TPL is working to balance the equation and create equitable access there.”

Ray Thomas, president of the Mableton Improvement Coalition, is a member of the Chattahoochee Working Group. Mableton is an unincorporated area in Cobb County with 40,000 residents, just five minutes from the Atlanta city line. The coalition is determined to provide residents with more river access along Mableton’s 2 miles of riverfront, including a new green space called Discovery Park at the River Line. The community is remarkably diverse; its population is 44 percent Black, 28 percent white, and 23 percent Latinx. About 12 percent of residents lived in poverty in 2018. According to TPL’s own data, across the United States, parks in majority-nonwhite neighborhoods are half as large and serve nearly five times more people than parks in majority white neighborhoods.

As Climate Threats Increase, the Holistic Conservation Imperative Grows

Across the country, in California, Trust for Public Land is planning a similarly ambitious series of land protections in coastal regions between Los Angeles and San Francisco. There, the TPL-led Central Coast Climate Conservation Initiative centers, as the name implies, on climate—both in terms of implementing nature-based climate strategies and making communities more resilient. As with TPL’s conservation work elsewhere, the California program seeks to reduce the impacts of extreme heat, drought, wildfire, and flooding while boosting equitable climate investment.

Trust for Public Land data scientists are busy doing GIS analyses of lands in a five-county region along the coast, identifying the greatest conservation needs in the area. And Christy Fischer, a senior project manager in California with TPL, is meeting with community groups, including rural, Latinx, and Indigenous representatives, to integrate their priorities, with a goal of partnering on several landscape-scale conservation programs in the coming years.

The initiative reflects Trust for Public Land’s own strategic plan, which puts an emphasis on climate, equity, and biodiversity, as well as the state of California’s Natural and Working Lands Climate Smart Strategy.

At a day-long Trust for Public Land workshop in Santa Cruz in September 2022, Californians from five counties engaged in “the nitty gritty of maps,” as Fischer put it. “Some people marked up large physical maps where they wanted to see land protected, while others were more comfortable using digital maps,” she recalls. “People were very familiar with conservation opportunities near where they live.”

Neal Sharma, of the Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN), is partnering with TPL on the vision for protecting California’s Coast Ranges. “It’s a priority area for us because of urban sprawl and habitat fragmentation,” he says. “Christy and her team are bringing a rigorous ecological lens to the project, but also a sensitivity to the community engagement side of things.”

“One thing that I think sometimes gets separated is the interrelationship between climate adaptation and resilience and biodiversity,” added Sharma, a senior manager of WCN’s California Wildlife Program. “Intact, connected, high-quality habitat and, ultimately, smart land-use decisions are going to be ever more important with climate change in the coming decades.”

By Conserving Hallowed Ground, We Ensure a Vibrant and Sustainable Future

On Hawai‘i’s Big Island, where the 175-mile Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail hugs the western and southeastern shores, the perennial threat to the land itself, as well as ecosystems and Indigenous culture, is development. Trust for Public Land has worked hand in hand with community groups to protect not only the trail, but also swaths of land abutting the trail at the southern tip of the island.

“People have seen what has happened to other parts of the island where all the big resorts are,” observed Lea Hong, TPL’s Hawai‘i state director. “They have watched over and over as resorts or residential luxury development have closed off access to the coast, and they didn’t want that happening here.”

This fall, Trust for Public Land will convey nearly 2,000 acres to the Ala Kahakai Trail Association, a local nonprofit. Known as Kiolaka‘a, the land is part of an ahupua‘a, or traditional Hawaiian land division extending from the mountain to the sea in the Kaʻū District of Hawai’i Island. The undeveloped property includes such natural and cultural resources as portions of an ancient Indigenous settlement, a cave system, heiau (places of worship), and an intact native dryland forest.

The transaction was the latest in a series of TPL projects that have conserved 24,000 acres in the Kaʻū region, beginning with Honuʻapo Fishpond in 2006, and expanded access to the Ala Kahakai Trail. The trail association now controls and manages much of that land.

Keoni Fox, a director and vice president of the Ala Kahakai Trail Association, says the projects ensure that future generations will come to know and love the land. “These are the missing pieces of this puzzle,” he says, referring to the acquisitions of recent years. “This area is still in a pretty pristine state, with natural and cultural resources. This part of the coast is the reason people love living here. For the Native Hawaiian community, these areas represent ancient fishing grounds where we can still do subsistence fishing.”

Conserving Historic Land and Places Facilitates Connection and Learning

Our desire to connect to our past is the impetus behind our efforts to preserve sites with significance for Black history and culture.

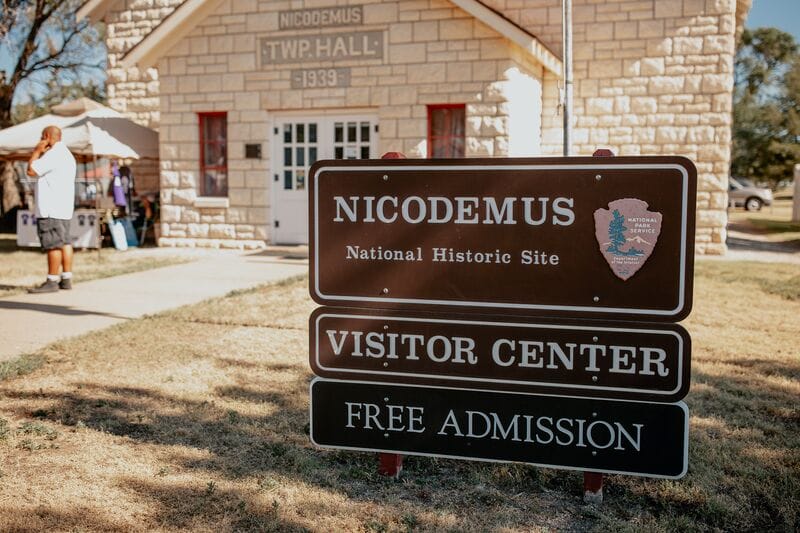

One such undertaking centers on Nicodemus, a town in Kansas where, in 1877, 300 newly freed Black Americans arrived to start a new life in the West. A symbol of their tenacity and enterprising spirit, Nicodemus is the oldest—and only remaining—Black settlement west of the Mississippi River.

Protecting public land doesn’t have to take the shape of a sweeping landscape or even a green outdoor space. As in the case of Nicodemus, acquiring and protecting a small plot of land can contribute to community placemaking and sometimes results in critical built infrastructure.

While only a small number of residents remain in Nicodemus full time, every July hundreds of former residents and descendants of the founders return for a weekend of festivities as part of the annual Emancipation/Homecoming Celebration.

A new chapter in Nicodemus is now unfolding. Designated a National Historic Site a quarter century ago, Nicodemus lacked a permanent visitor center. Trust for Public Land is helping the town to rectify that. With support from Sony Pictures and the National Park Foundation, we recently acquired land there and donated it to the National Park Service, which will build a dedicated visitor center.

The current visitor center is located inside the Nicodemus Township Hall. In addition to its administrative functions, the hall had, over the years, hosted community dances, gatherings, and meetings. Given that the town hall doubles as a visitor center, those events are now constrained.

“A new visitor center will return Township Hall to the community and open up the space so residents can use it the way they historically have for generations,” says Dr. Jocelyn Imani, Trust for Public Land’s national director of Black history and culture. “I believe in self-determination and people being able to do what they want with their resources.”

LueCreasea Horne, a park ranger based at the Nicodemus National Historic Site, is a sixth-generation descendant of original settlers Thomas and Zerina Johnson, who arrived in 1877 with three children after their emancipation. (Their former owner, slaveholder Richard M. Johnson, was vice president of the United States under President Martin Van Buren—thus the family’s surname.)

For Horne, whose own family moved to the Nicodemus area from Kansas City when she was 12, a permanent visitor center will allow the site to properly convey the community’s rich history. “It will make the descendants and the people of Nicodemus really feel like we are official,” said Horne, now 44, “and that we’re not the stepchild of the National Park Service.”

—LueCreasea Horne, park ranger and sixth-generation Nicodemus descendant

Self-Determination and the Power of Holistic Land Conservation

While the story of the Butte Falls Community Forest, some 1,500 miles west of Nicodemus, centers on a natural landscape rather than a collection of buildings, both communities’ narratives exemplify self-determination and the power of holistic conservation.

“I was looking at one of these nice trees as I drove by, and I thought, ‘Well, we could cut this tree one time and sell it and get some money out of it and it’s gone,’” Hamann, the longtime Butte Falls resident, reflected. “Or we could turn this into a little bit of ecotourism and sell this tree over and over and over again. It’s been an amazing journey for our little town, with no money, to end up with this piece of land to protect us from fire and give us community health.”

Lisa W. Foderaro is a senior writer and researcher for Trust for Public Land. Previously, she was a reporter for the New York Times, where she covered parks and the environment.

Donate to become a member, and you’ll receive a subscription to Land&People magazine, our biannual publication featuring exclusive, inspiring stories about our work connecting everyone to the outdoors.