In Hawai‘i, a grandson follows ancient footsteps to help save his family’s ancestral home

The Hawaiian scholar Mary Kawena Pukūʻi wrote more than fifty books about the language and culture of Hawaiʻi. With titles like The Echo of Our Song: Chants and Poems of the Hawaiians, her scholarship helped spark the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s. The movement celebrated Native Hawaiian identity, pushing back against growing Westernization and a century of policies that had long suppressed the islands’ indigenous culture, from banning teaching and speaking the Hawaiian language in school to discouraging cultural and spiritual practices like hula.

Mary Kawena PukūʻiPhoto credit: Wikipedia

Mary Kawena PukūʻiPhoto credit: Wikipedia

Pukūʻi, who was born in 1895, learned about her ancestors’ traditions from her own grandmother, Na-liʻi-poʻai-moku. Her grandfather, Ke-liʻi-kanaka-ʻole-o-Haililani, had been a medicinal expert and an expert on fish habitat and population conservation. They had lived in a house in an ancient fishing village called Waikapuna, situated on a windswept coastal bluff in the Kaʻū area, on the southern tip of the Big Island. But the 1868 eruption of the Mauna Loa volcano triggered a tsunami that destroyed homes and contaminated the few freshwater sources the residents relied on. The devastation forced Pukūʻi’s family and others to abandon the village and move inland.

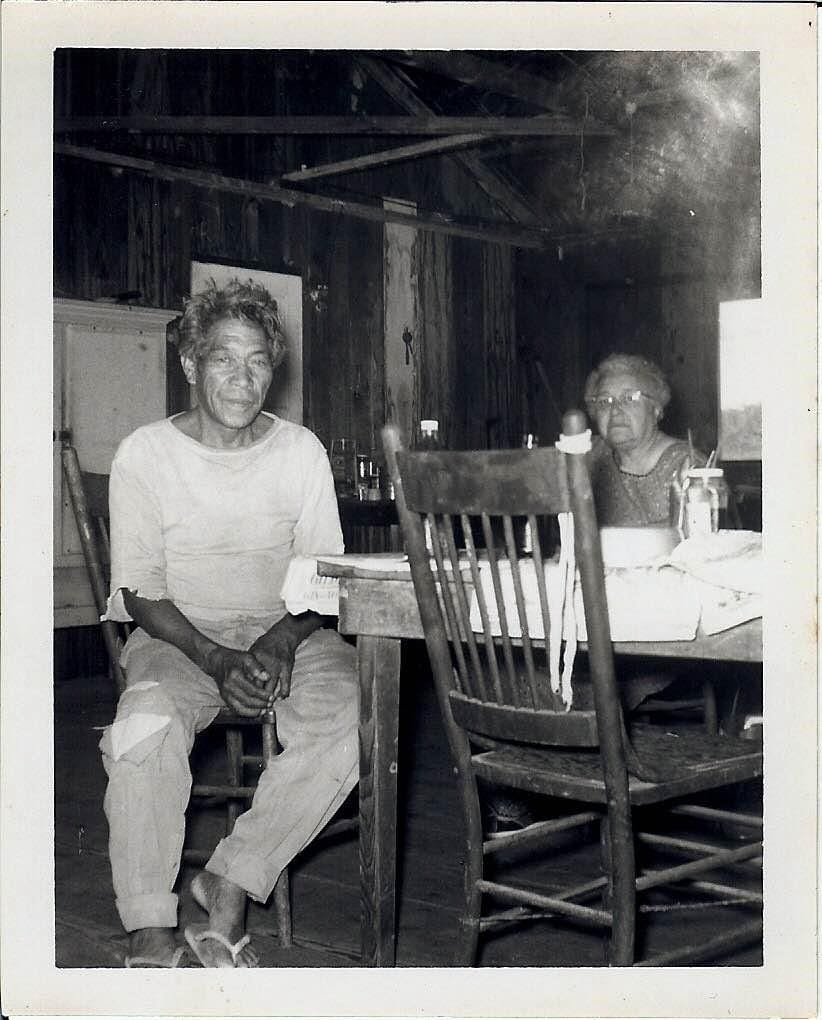

Pukūʻi worked for the Bishop Museum. In 1960, she returned to Kaʻū to gather oral histories for research and preservation, and she brought along her grandson, Laʻakea Suganuma. He was only 10 years old, but he remembers listening intently while she recorded interviews with elderly residents about their earliest memories, habits, and traditions. Among her interview subjects was a “famous old fisherman near Waikapuna,” Suganuma recalled. “He lived in a shack and showed my grandmother how to make a fish net.”

Laʻakea Suganuma took this photo of his grandmother, Mary Kawena Pukūʻi, recording an oral history from a “famous old fisherman near Waikapuna,” Suganuma says. Photo credit: Laʻakea Suganuma

Laʻakea Suganuma took this photo of his grandmother, Mary Kawena Pukūʻi, recording an oral history from a “famous old fisherman near Waikapuna,” Suganuma says. Photo credit: Laʻakea Suganuma

One such tradition Suganuma remembers hearing about from his grandmother is the idea of aloha ʻāina, or “love of the land.” “It’s something that is very deep in the Hawaiian soul,” he said. “You take care of the land, the land takes care of you.” By that time, the area where Pukūʻi’s family once lived was privately owned ranchland. But it was still rich with living memories and vital connections to Hawaiian heritage. Pockets of native vegetation thrived among the foundations of one-time family homes and vestiges of heiau (temples). Waves washed over rocky tide pools and crashed against cliffs, where sea caves served as burial sites for family members’ remains.

So when Suganuma learned from another Kaʻū descendant named Keoni Fox that the ancient fishing village at Waikapuna was under threat from development, he recoiled. He was worried that this stunning, hallowed landscape would be forever changed, destroying the connections to the land that his grandmother had dedicated her life to documenting and passing on to the next generation. He wrote letters against the development proposal, testified before funding committees in Honolulu, and traveled to Waikapuna to show support. Joining the effort was a matter of duty and responsibility to his ancestors, he says.

La‘akea Suganuma’s grandmother, Mary Kawena Pukūʻi, gathered oral histories from elders living on the windswept southern coast of Hawai‘i Island. Photo credit: Alec Freeman

La‘akea Suganuma’s grandmother, Mary Kawena Pukūʻi, gathered oral histories from elders living on the windswept southern coast of Hawai‘i Island. Photo credit: Alec Freeman

The Kaʻū community has long fought to protect its beloved coastline from development. Among those who didn’t want to see Waikapuna given over to luxury development was Keoni Fox, whose mother’s family, the Keanu ʻohana, has ties to the area around Waikapuna. Fox is Native Hawaiian and a member of the board of the Ala Kahakai Trail Association. The nonprofit protects and revives the ancient trail that encircles the Big Island, passing through Waikapuna.

Known in ancient times as alaloa (long trail) or alanui (big trail), by the 1990s, the path was overgrown, with many stretches in private hands and off-limits to the public. But in 2000, the federal government designated the path the Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail in order to preserve Native Hawaiian culture and protect the island’s indigenous plants and wildlife. (ala kahakai means “trail by the shoreline.”) The 175-mile oceanfront corridor, hugging more than two-thirds of the island, includes wahi pana (“storied landscapes” of ancient legend), home foundations, and other important cultural sites.

Fox, an avid hiker, has spent many long hours on the Ala Kahakai. But he says the trail is much more than a recreation destination. “The association is not about protecting a hiking trail,” Fox said. “Its mission is to protect all of the natural resources around the trail and to honor the path of our ancestors—to bring the community and the descendants together, to build those connections.” Determined to do right by his ancestors, Fox mounted a campaign to save the 2,317-acre Waikapuna property. The first developer—who bought the land with intent to build more than a hundred luxury homes—defaulted on its loan after the 2008 financial crisis. The new owner, Fox hoped, might be more open to alternatives. “I reached out to the Trust for Public Land right away and said, ‘Look, this is a huge opportunity to maybe save this property,’” he recalled.

The Ala Kahakai passes through Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau National Historical Park. We helped expand the park in 2006.Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress

The Ala Kahakai passes through Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau National Historical Park. We helped expand the park in 2006.Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress

It wasn’t the first time that Fox had thought to partner with us. Since 1979, we’ve helped protect many special places along the Ala Kahakai Trail. “Waikapuna presented an unparalleled opportunity to preserve a set of cultural sites amid a strikingly beautiful landscape—one that is increasingly attractive to developers,” said Lea Hong, Hawaiʻi state director at Trust for Public Land. “It was a privilege to work with members of local organizations whose ancestors farmed and fished in this very location for many centuries.”

In late 2019, we purchased the land and transferred ownership to the Ala Kahakai Trail Association. The County of Hawaiʻi placed a conservation easement on the land, insuring that it will remain undeveloped in perpetuity. Two weeks later, we helped protect over 800 acres just east of Waikapuna, known as Kāwala, and we’re working on three more projects in the area: Kaunāmano, Manākaʻa Fishing Village, and Kiolakaʻa. Altogether, we’re working to preserve 6,000 contiguous acres of coastline, cultural sites, and pasture at the southern tip of the Big Island.

For now, the Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail is the only path through Waikapuna. But Fox would like to resurrect two trails that once connected the fertile fields upslope in the ancient farming community of Nāʻālehu to the bounty of the sea at Waikapuna. Today the trails are overgrown and abandoned, Fox explains, “But they are on old maps, and we would like to survey them and revive them. We will be working with archaeologists to map those out.”

For his part, Laʻakea Suganuma says protecting the land where his grandmother spent her earliest years, and whose people contributed to her important research, is a fitting tribute to their memories. “I’m very happy,” he said. “I’m sure the ancestors are happy too.”

Laʻakea’s daughter Pelehonuamea Harman, and her daughter Kalamanamana (dancing), represent the 7th and 8th generation tied to Waikapuna. Pele is on the Waikapuna stewardship committee, and both advocated and testified to save the property.Photo credit: Laʻakea Suganuma

Laʻakea’s daughter Pelehonuamea Harman, and her daughter Kalamanamana (dancing), represent the 7th and 8th generation tied to Waikapuna. Pele is on the Waikapuna stewardship committee, and both advocated and testified to save the property.Photo credit: Laʻakea Suganuma

These days Suganuma lives in Honolulu, where he’s a master of Hawaiian martial arts and an expert on ancient weaponry. But as soon as it’s safe to travel again after the pandemic, he plans to return to Waikapuna. He wants to talk to members of the community about resurrecting sustainable practices, whether preventing the depletion of local fish stocks or coaxing native plants from the soil. “It’s a matter of saving all of these things and bringing back the old practices that have not been done since my great-great-grandfather,” he said.

He also wants to hold an ʻawa ceremony at the ancient fishing village in Waikapuna, where his ancestors lived more than 150 years ago. He’d bring ʻawa, a beverage that Polynesian people have used in rites for centuries. “The purpose is to commune with those in spirit, express our aloha to them and each other and ask for inspiration to guide us. Everyone, in order, will have the opportunity to express themselves, including any thoughts given by our unseen attendees,” he said. “It’s an old, very Hawaiian ceremony of gratitude in which you commune with the ancestors in a real sense, bringing them forth to join us.”